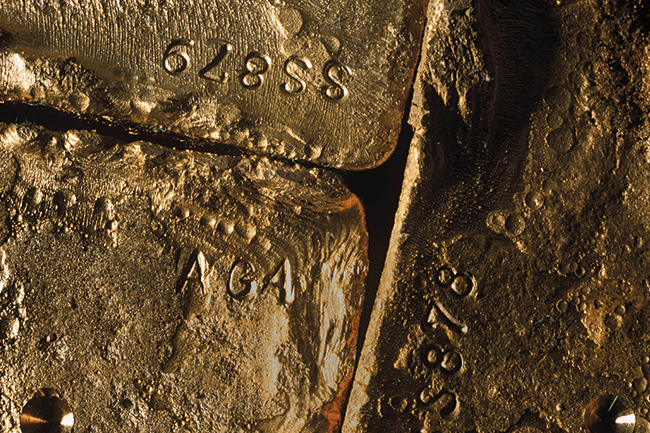

Ghana’s pre-independence name, the Gold Coast, is an apt indication of how important and ancient its relationship is with the precious metal.

When the first Europeans, the Portuguese, arrived to trade with the area in 1471, the various inland kingdoms were long renowned for the rich quantities of alluvial gold they had available for trade. Long before that, gold from this part of the continent was making its way to Europe via camel routes run by Arabs across the Sahara.

Today, even after big and highly lucrative discoveries of oil offshore, gold is worth more than cocoa (the main agricultural crop) and the booming oil revenue combined. According to Reuters it made up nearly 30% of foreign exchange in 2012. In total, exports were around US$5.6 billion.

Ghana is Africa’s second-largest producer of gold after South Africa, and in 2012 it mined more than 90 tons. Since independence from Britain in 1957, multinational resources companies such as AngloGold Ashanti, Gold Fields and Newmont have established major mines.

Despite the established industry, the declining gold price last year has had a huge impact on the sector. Near the end of 2013, Bloomberg announced that Ghana’s gold output had dropped by 18% in the third quarter after some companies slashed production.

From July to September, 840 600 ounces was mined, down from 1.02 million ounces in the second quarter.

By contrast, bauxite and manganese (the country’s other two most important minerals) climbed respectively in the same period to 246 759 tons from 193 876 tons and 520 431 tons from 323 299 tons. Even diamonds, the fourth-major mining activity, managed an increase – 42 669 carats, up from 40 869.

Cost-cutting has filtered through to staff as well. Both Newmont and AngloGold Ashanti are planning retrenchments, while the Wall Street Journal reported that about 4 000 jobs in the sector would be shed between all the prospecting companies.

The falling gold price has also impacted another part of Ghana’s mining industry – small-scale illegal miners.

Working back-breaking labour intensive diggings – many times encroaching on concessions held by the big companies – they have long been part of the country’s mining set-up. In recent years, however, they have become an environmental, health and safety as well as security issue.

The falling gold price has also impacted another part of Ghana’s mining industry – small-scale illegal miners

It is not often that a country’s chamber of mines resorts to hard-hitting language in an official document, but an indication of the ‘canker’ that illegal mining has become is clearly visible in the Ghana Chamber of Mines’ 2012 annual report. It states: ‘Its economic implications are dire for the country. Unfortunately, the Chamber of Mines’ repeated advocacy for government to take a leadership role to deal decisively with the menace went unheeded.

‘This was when the illicit activity occurred mainly on encroached concessions of member companies. While their focus has not shifted entirely from member companies’ concessions, today illegal miners mine every conceivable land or water body where they expect to find gold.

‘Given the nomadic nature of their activities, illegal miners leave in their trail polluted water bodies, craters and general destructions to flora and fauna.

‘Various experts including the Ghana Water Company have cautioned that the nation may face an imminent catastrophe, considering the rate at which its water bodies are being destroyed primarily through illegal mining activities

‘While it is acknowledged that small-scale miners are expected to operate responsibly, the compliant ones are in the acute minority. Generally the difference between small-scale mining operations and illegal mining is not distinct. Not surprising they both contribute minimally to the nation’s kitty.

Although these concerns have not been at the fore of major policy discussions on the menace, the fact that they both contribute more than a third of the nation’s gold production makes the situation worrying,’ the report stated.

Apart from thousands of Ghanians involved, in early 2013 it was estimated that around 50 000 Chinese were implicated in illegal mining too, often using locals as a front.

The government was eventually forced to act and in May 2013 began a crackdown with mixed success. Activating a law forbidding foreigners from engaging in small-scale mining operations, authorities started arresting hundreds of illegal miners and expelling foreign nationals.

According to the Guardian, in only two months (June and July) nearly 4 600 Chinese were deported. Others left voluntarily. It is too soon to see whether the crackdown will have a lasting impact. Even state officials have said the vastness of scale makes it difficult to quantify.

To add to the big companies’ headaches, in November Ghana’s Minister of Finance Seth Terkper said the government was planning to introduce a mining windfall tax.

‘A committee is reviewing all stability agreements, incentives and the windfall profit tax that could not be passed in 2012. In due course, government will reintroduce the bill in parliament after completion of the consultations with all stakeholders,’ he told Reuters.

‘While it is acknowledged that small-scale miners are expected to operate responsibly, the compliant ones are in the acute minority’

Ghana tried to introduce a windfall tax in 2012, but the provisional bill for a 10% levy was withdrawn before it reached parliament. Opposition has been widespread and echoed by the chamber of mines, which warned that it would discourage investment.

The chamber also pointed out another huge problem for the country in its efforts to attract investors – the poor condition of infrastructure. In the west, the Ghana Manganese Company owns and operates Nsuta, the country’s only manganese mine. Endowed with a very high manganese-to-iron ratio, making it ideal for alloy and manganese metal production, the mine is only about 60 km by rail from the port of Takoradi. Yet logistics problems continually hamper export.

‘The deplorable state of the western line had been a major problem for the bulk producers of manganese and bauxite,’ said the chamber in the 2012 report.

‘As a result, Ghana Bauxite Company has completely stopped hauling by rail and solely transports its ore by the less cost-effective road mode. Ghana Manganese Company is the last industrial user of rail haulage in Ghana, although on a reduced operational level.

‘On two occasions Ghana Manganese Company has offered to directly invest in the rail infrastructure, but until now the authorities are yet to accept the company’s offer.

‘Despite assurances of government through major policy statements that the western rail line will be fixed, regrettably these promises have not been fulfilled. Naturally, this has adversely impacted the realisation of the strategic objectives of these companies.’

The issues on land aside, the most interest in Ghana’s resources lies offshore. Since the first pumping in December 2010, the Jubilee oil field off the coast has shown great potential. It is operated by the British company Tullow Oil, and Kosmos Energy has a stake. Oil exports were worth US$3 billion in 2012, according to the central bank.

In July last year, Nana Boakye Asafu-Adjaye, CEO of the government-owned Ghana National Petroleum Corporation (GNPC) said Jubilee’s oil production will increase from 110 000 barrels per day (bpd) to 250 000 bpd by 2021.

He said ‘in the next five to eight years we will be spending US$20 billion’ in developing not only Jubilee but also other fields.

Tullow, Kosmos and Anadarko Petroleum, PetroSA and the GNPC are developing the Tweneboa-Enyenra-Ntomme project, better known as TEN. ‘First oil from TEN could be in late 2016,’ Asafu-Adjaye said in an interview with Bloomberg.

According to Asafu-Adjaye the field could have reserves of 245 million barrels. Peak production is expected to be around 76 000 bpd.

GNPC is also exploring the oil potential of the Voltaian basin, which is onshore and covers about 40% of the country.