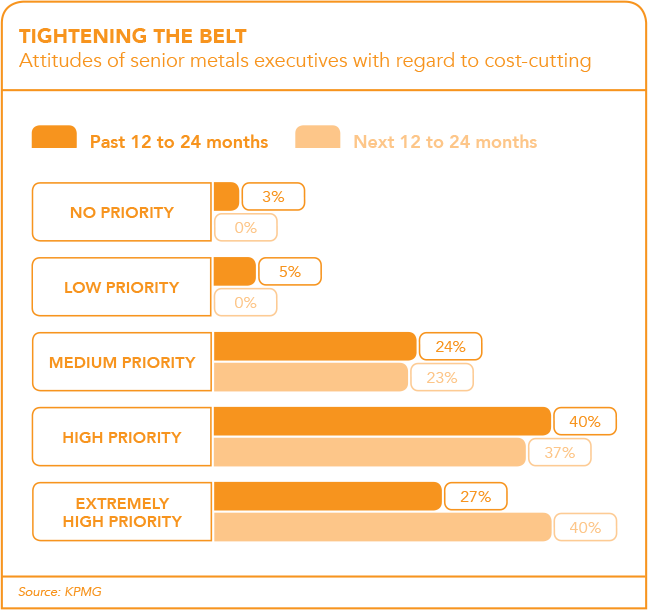

Heading into 2017, a scan of mining on the African continent shows that the big international mining companies have consolidated extensively, while everyone in the business, from the biggest gold mines to most local quarries, has tightened efficiencies.

National mining jurisdictions are, of course, inherently much less nimble and market responsive. Amid a mixed bag, Botswana remains attractive and others, such as Zambia, are implementing the improvements necessary to attract new investment. However, some seem to be going backward.

The big mining companies faced a debt crisis when revenues fell sharply after mid-2014. Those with the most gearing – Anglo American and Glencore – were punished the hardest by the markets. The big players, especially the big four – BHP Billiton, Glencore, Rio Tinto and Anglo American – have been engaged in determined processes of reform since 2015. All have sold assets and improved operational efficiencies in the past 18 months.

Anglo American promised to reduce debt to less than US$10 billion in 2016 and has met the target with ease. By the end of last year the company had disposed of eight major assets, including all its coal mines in Australia and all platinum holdings in South Africa bar one capital-intensive opencast mine.

After being the worst share performer on the London Stock Exchange (LSE) in 2015, Anglo American has been the best in 2016. Another company that has restructured and recovered is Glencore – the second-worst performer on the LSE in 2015, behind Anglo American. The Swiss-based miner had incurred considerable debt (US$30 billion) during an aggressive expansion drive in the boom years. When commodity prices plummeted, there was serious talk of Glencore being forced to file for bankruptcy.

However, the company responded ruthlessly. It sold assets worth up to US$5 billion and embarked on a strategy of ‘shuttering’ (closing down) production to push up the prices of some of its biggest commodities – zinc and copper. The results were spectacular. The day after Glencore announced it was to halt 4% of the world’s zinc output, the metals price in London jumped 10%.

In the second half of 2015, Glencore suspended production at two high-cost copper mines in the DRC (Katanga) and Zambia (Mopani). Combined, the two mines accounted for 400 000 tons or 2% of global copper production.

While there was speculation at the time that Glencore was trying to drive the price higher, what was probably more important to the company was that it intended spending US$1.1 billion to modernise these mines and thus bring down operating costs.

The 18% increase in the copper price in late 2016 was not due to any supply squeeze by Glencore but rather to an up-tick in demand in the Chinese construction market, combined with hopes for an infrastructure spending surge in the US under a Trump government.

The joint London- and Sydney-listed Rio Tinto had the smallest debt problem of the big four. This makes its October 2016 decision to sell its stake in Guinea’s Simandou iron-ore project all the more notable.

Although the iron ore price has climbed about 60% in late 2016, this was not enough to convince Rio Tinto to stay the distance.

The Simandou project has indeed been a marathon. Labelled the world’s largest as yet unmined iron-ore deposit, it is a textbook case for the perils of political risk in under-developed mining jurisdictions.

The Simandou deposit, estimated at more than 2 billion tons of high-grade ore, was discovered in 1998 and Rio Tinto bought into mining rights soon afterwards.

However, in 2008, Guinea’s ailing dictator Lansana Conté signed an executive order that transferred these rights to a trust controlled by Israeli businessman Beny Steinmetz, who sold them on to Brazilian iron-ore mining giant Vale. After litigating in New York, Rio Tinto regained its rights.

In May 2016, Rio Tinto published a feasibility study – including plans for a railway to a new-build harbour on the Guinea coast – and announced it was forging ahead with the project. Yet in October, the company announced that it was selling its 46.6% stake to Chinese company Chinalco, with which Rio Tinto has had a long-standing relationship.

Two factors seem to have intervened. Firstly, the Anglo-Australian miner had appointed a new CEO, Jean-Sébastien Jacques, in July. Jacques, who forged his reputation in the company’s copper division, is believed to want to refocus the company on that commodity. Secondly, Rio Tinto announced that the International Finance Corporation (IFC), a branch of the World Bank, had bailed out of the project. IFC participation in resources projects is regarded as a guarantee of viability, so the bail-out looked like a serious vote of no confidence. But in November, the IFC issued a statement saying it remained ‘fully supportive’ of the project.

Whatever the outcome in Simandou, the point is that the project has been all but stalled for nearly two decades. There have been non-mining setbacks, such as the outbreak of the Ebola virus epidemic in West Africa in 2014, with Guinea at its epicentre – but generally, it has been the political and legal conditions – the quality of the mining jurisdiction (in other words policy) that has weighed most heavily on the project.

In the most recent Fraser Institute survey of global mining jurisdictions (for 2015, released in March 2016), Guinea ranked lowest of all the African countries rated. The opinion survey, which aggregates perceptions of the policy environment and mineral wealth to produce an Investment Attractiveness Index, ranked Guinea 103 out of 109 jurisdictions.

Generally, the Fraser Index found that African mining jurisdiction had ‘improved slightly’. But the institute’s rankings are based on 2015 perceptions, and events have moved on since then.

Zambia revised its mining legislation and reduced taxes on mining companies. That sets an example to governments to support their mining investors while commodity prices are only marginally off the cyclical lows they reached in 2015.

Tanzania, on the other hand, has caused jitters by passing a law that insists all foreign miners with investments in the country list 30% of the company on the Dar es Salaam Stock Exchange.

In South Africa, relations between government and the mining industry are frostier than they have been for some time. The industry is awaiting the publication of a new basic mining act, the amended Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act, as well as the black economic empowerment provisions of the sector’s Mining Charter that will spell out which proportion of their operations require ownership by indigenous black South Africans and under what conditions.

The mining industry’s representative organisation, the Chamber of Mines, claims that it has had no input into this important body of regulation. However, it has been shown drafts – in a process that it says the Department of Mineral Resources believes is adequate ‘consultation’ – and thinks these are onerous. It argues that the executive powers that the draft act vests in the minister and other conditions – such as increasing domestic content requirements from 40% to 70% – are burdensome.

Some suggest the South African industry, probably the most established in the world, is in the doldrums. Graham Schwikkard of Johannesburg consultancy Datta Burton argues it is ‘on an investment strike’. Official figures suggest that the industry is investing less than it needs to in order to replace current production. And while total year-on-year production figures rose slightly in the third quarter of 2016, the 18% drop in the first quarter of 2016 was the biggest ever recorded.

Neal Froneman is chief executive of Sibanye Gold, the company that bought most of the platinum assets sold by Anglo American. Sibanye Gold took delivery of three shafts and associated infrastructure near Rustenburg on 1 November 2016, adding it to its existing gold-mining portfolio. Sibanye is now, by its own account, the biggest private employer in South Africa.

Froneman, however, is not a happy man. At the end of November, he told Reuters he was witnessing the worst sentiment he had seen from an investment perspective.

He speaks on behalf of a company that operates wholly within one national jurisdiction and cannot spread risk across the globe, as can the big four.

The large international players can mitigate against uncertainty with a spread across continents and commodities. More localised operators, however, will have to find a way to deal with the conditions 2017 will bring.