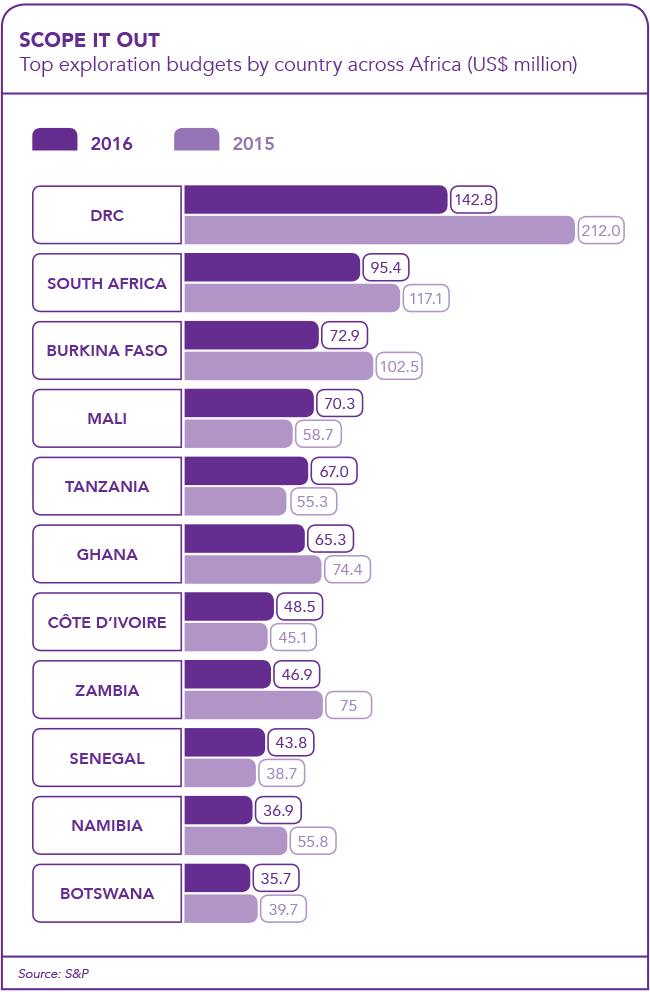

When resources prices plummeted in 2014 and 2015, one of the biggest casualties was exploration expenditure. Mining is a cyclical industry and prospecting is always the first casualty when cash flows come under pressure. According to S&P Global Market Intelligence’s 2017 Corporate Exploration Strategies report, worldwide exploration figures for the industry (excluding non-ferrous metals) fell by 66.5% between 2012 and the end of 2016.

Of course, these figures hide a multitude of variations across different minerals, types of exploration and jurisdictions. Diamonds and gold, for example, are less impacted by slowing Chinese industrial demand than industrial commodities such as iron ore, coal and copper. In 2016 diamond miner De Beers Consolidated Mines actually increased exploration spending in South Africa as it both ramped up its US$2.1 billion Venetia mine and looked for further discoveries in the jurisdiction.

Diamond mining in Southern Africa is a particularly good example of the need for intensive exploration of uncharted territory, referred to in the industry as greenfield exploration. Yet to be discovered kimberlite pipes – geological formations that may contain diamonds – are likely to be contained in ancient rocks, buried under younger successions. In Southern Africa, it is the sediments of the Kalahari formation that hides the kimberlite. Diamonds have paid off for De Beers parent Anglo American, which owns 85% of the company. The former increased both diamond output and sales for the first quarter of 2017, generating improved cash flows. Sales more than doubled year-on-year to 14.1 million carats as the company pushed more of its stockpile into the market.

S&P Global Market Intelligence points out that in 2016, brownfield exploration (which is essentially further exploration of an already identified ore body, with a view to profitably extending current mining operations) outdid greenfield spending in Africa for the first time in many years. Brownfield exploration is a type of expenditure that can be expected to hold up better on a weak commodity as companies seek to maximise returns for existing mines.

Reasonably strong brownfield work is the reason South Africa has managed to hold on to second place for exploration spending on the continent. But it is a long way behind the DRC, which accounts for 16% of the continent’s entire exploration spend (US$142.8 million). South Africa has fallen from its dominant share of the African exploration budget prior to 2007. Neal Froneman, CEO of Sibanye Gold, now South Africa’s biggest private sector employer, stated in April that regulatory and political risk in South Africa was so high that his company would not be investing in the foreseeable future. Sibanye Gold announced that it was cancelling a large gold and uranium tailings treatment project on the West Rand.

The South African industry continues to bleed with somewhat positive March figures from Statistics South Africa – indicating that job losses in the industry had stabilised – followed closely by the announcement of large-scale job cuts (up to 1 000 people) at Implats’ Marula platinum mine.

Platinum is especially troubled at the moment. The US Geologic Survey notes that ‘companies continued efforts to cut costs by lowering production, selling or closing mines and reducing the workforce’. The sector’s woes demonstrate the close relationship with the global market: platinum was trading at US$940 per oz at the beginning of May, down from nearly US$1 200 in mid-2016.

Sibanye Gold purchased Anglo American’s Rustenburg Platinum Mines for US$4.5 billion in September 2015. But with its negative view of the South African jurisdiction, the company currently looks as if it is trying to follow Anglo’s lead and diversify away from the country. It is in the process of negotiating the purchase of a massive platinum asset in the US. Stillwater Mining Company is the biggest platinum producer in the US. It will be Sibanye Gold’s first offshore asset and is set to cost the company US$2.2 billion. The deal has yet to be finalised but by April it had been given approval by the US regulator as well as Sibanye Gold’s shareholders, who have been asked to support a US$1 billion rights issue.

A second significant Anglo sale was its off-loading of three thermal coal mines, all with existing contracts to supply South Africa’s electricity supply company (Eskom) in April 2017 for ZAR2.3 billion. The buyer is Seriti Resources, a 79% local black-owned entity.

The transfer of mining assets to black-owned companies has become a political football in South Africa in recent years.

One of Froneman’s major criticisms of the regulatory environment has been the lack of certainty regarding the degree to which government would require black ownership before awarding mining rights. The South African industry’s Mining Charter, originally an industry initiative, requires companies to meet an objective of 26% black ownership. The charter, however, became a matter for state regulation when it was incorporated into the 2004 Minerals and Petroleum Resources Development Act.

The industry has been waiting for an updated version of the charter and the act since 2014. An important amendment that many mining companies have been pushing for pertains to the issue of 26% black ownership, in terms of once a company has met the target, it should be regarded as ‘perpetually empowered’, even if black shareholders cash out, thereby reducing black ownership to below 26%. Mosebenzi Zwane, Minister of Mineral Resources, has taken issue with this position but has failed to produce the long-promised draft legislation, which would clarify his alternative position. His department missed its third promised deadline at the end of March, without explanation.

With the acquisition of Anglo’s thermal coal assets, Seriti Resources may have positioned itself to become the local mining champion, For several years, Eskom has been promoting domestic black ownership in coal mining by insisting that it would only grant contracts to supply coal-burning power stations to mines that are at least 50% black-owned. But the most significant advocate of a local mining champion has been the Public Investment Corporation (PIC), the biggest investment entity in the country.

Seriti has some way to go before it becomes the domestic mining champion envisaged by the PIC. Seriti’s most prominent shareholder, Mike Teke, who is the former president of the Chamber of Mines of South Africa, has stated the ambition he and his colleagues have to pursue this end.

Possible short-term additions to the new company’s portfolio are Anglo’s export coal mines and its New Largo project, which is intended to supply coal to the gigantic Kusile power station, currently under construction in South Africa’s Mpumalanga province.

The possible purchase of a holding in Kumba Iron Ore has to be somewhere on the agenda too. The PIC has a significant interest in Anglo American’s sell-off as it is Anglo’s largest South African shareholder with 14.5% of its JSE-listed shares. The PIC’s original position – that Anglo American should sell iron ore, coal and platinum resources in a single bundle to a black domestic diversified miner – appears to have lost out to the piecemeal sell-off strategy preferred by the mining major, perhaps because the sheer price of a once-off sale would have been prohibitive.

The sales so far have been a win on all fronts for Anglo American. It has retained plum assets including the Mogalakwena open-pit platinum mine, its export coal mines, the Venetia diamond mine and the company’s 70% stake in Kumba Iron Ore. It has paid off debt, consolidated its positioning as a major international player and at the same time done its bit to significantly advance the transformation of the South African industry.

While Anglo American has complained about the government pressure it has been under to restructure its holdings within the South African jurisdiction, this sale has been conducted on its own terms. The buyers are in both cases experienced miners who paid a fair price for workable assets. Despite some negative publicity around the politics of the jurisdiction, deals are still being made on rational business grounds.