Earlier this year, Ethiopia overtook Kenya as the largest economy in East Africa. This has been on the back of an economic growth rate of between 8% and 11% over the past decade. Ethiopia, Africa’s second most populous country (105 million people), has also been named the world’s fastest-growing economy in 2017. This is of course from a low base – Ethiopia was the world’s second-poorest nation in 2000.

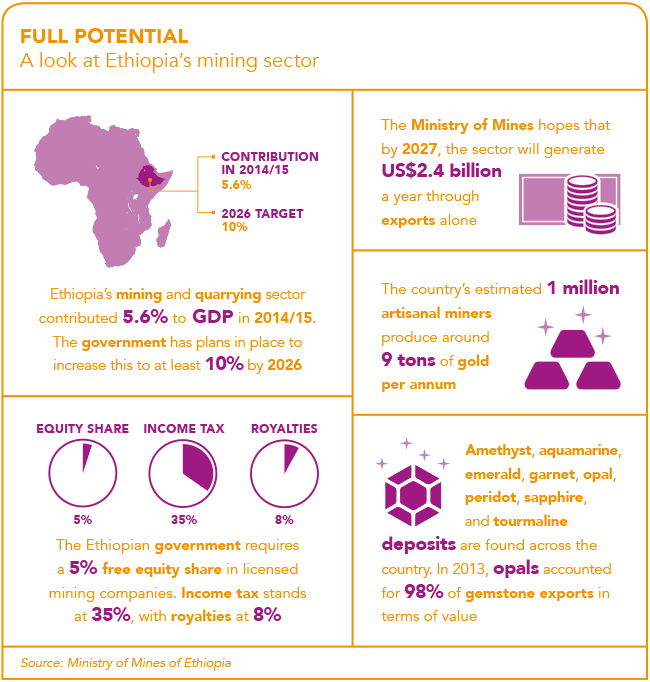

However, despite what the World Bank describes as ‘huge potential’, mining has not been among the key drivers of the country’s growth. According to the National Bank of Ethiopia, mining and quarrying contributed just 5.6% to economic expansion in 2014/15 – an almost insignificant provision next to industry at 29.4% and services at 46.1%. Yet mining is developing and has risen from a contribution of less than 1% in the late 1980s.

Ethiopia is known to possess mineral wealth. The Geological Survey of Ethiopia, which continues to refine its data (only 74% of the country is mapped and at a low-quality scale), has identified viable deposits of gold, base metals (including 70 million tons of iron ore) and other industrial minerals (such as potash, phosphate, tantalum and copper), as well as oil and gas.

However, the development of the industry has been long neglected in the face of Emperor Haile Selassie’s feudalism (1930 to 1974) and later a Marxist military government from 1974 to 1991. The subsequent civilian government has implemented a business-friendly growth regime in a manner often compared to Chinese capitalism.

One of the major areas of reform has been an enabling environment for mining, starting with the 1993 Mining Proclamation. In 2014, the Ethiopian government established a Mineral Market and Value Chain Develop-ment Directorate, located in the Ministry of Mines. It was tasked with increasing the minerals sector’s contribution to GDP to more than 10% within a decade.

Also in 2014, the government convened an extractive industries forum in Addis Ababa, with input from – among others – the World Bank, the UN Development Programme and donor departments from Australia, Canada and the UK. The meeting examined a report published by the Ethiopian government assessing the opportunities pinpointed by the national geological survey. In the same year, Ethiopia was admitted as a candidate to the Global Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative.

The 2014 forum marks the real start of the drive to develop a mining industry in Ethiopia. Among its activities was an examination of the enabling environment for mining investment, which was found to be extremely favourable. Royalty (8%) and corporate tax rates (35%) are significantly lower than most African jurisdictions while the 5% free carried equity to the state mining company is minimal.

Mining in Ethiopia has until recently been almost entirely artisanal. With about 1 million informal miners, the industry’s small contribution to formal GDP stands in stark contrast to its big impact on employment. Alluvial or ‘free’ gold has been mined since ancient times and gold still accounts for almost all of the country’s mineral export earnings. The artisanal sector also produces semi-precious gems, most notably opal.

These investor-friendly policies appear to be starting to pay off. For years, the major significant gold mine in Ethiopia was Lega Dembi in southern Ethiopia, which began production in 1998. This year, however, a second mine, Terakamti, located in the far north of the country and owned by Ezana Mining started production. Ezana is an Ethiopian company whose major investment is a US$17.8 million carbon-in-leach plant, built and brought into operation by a South African contractor, Manhattan Corporation.

Another gold miner, KEFI Minerals, is set to begin work on the Tula Kapi gold project as soon as Ethiopia’s wet season is over. The US$160 million project is an open-pit venture designed to work an ore body of approximately 50 tons.

However, the volumes mined in Ethiopia are small compared to the continent’s giant gold producers. Lega Dembi mines 4.5 tons a year and Terakamti’s initial ramp-up will deliver less than a quarter of that figure. By contrast, South Africa mined 165 tons in 2016, Ghana 95 tons and Tanzania 55 tons. Indeed, artisanal miners in Ethiopia still produce nearly two-thirds of the county’s gold. However, it is arguably the demonstration effect that is more important than production volumes. Ezana Mining has shown that development in the industry is possible.

It may well turn out that Ethiopia’s precious metals are less significant than its industrial minerals. The country is unusual in Africa in that it has embarked on industrialisation in advance of developing a mining industry – a sequenc-ing that may result in a much more balanced development than that associated with the ‘resource curse’ in so many other African countries. Ethiopia has bet heavily on provision of public infrastructure – highways, electricity and rail connections – as a mechanism to leverage light industrial growth.

The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance dam on the Blue Nile will have the capacity to generate 6 000 MW of power, and will be the largest single hydroelectric project in the world since the Chinese Three Gorges dam, which was completed in 2012. The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance dam has been under construction since 2011 and is on schedule to be completed later this year.

Ethiopia’s major export link, the standard gauge electrified Addis Ababa-Djibouti railway, was inaugurated in October last year. In 2014, a new six-lane highway covering the 84.7 km between Addis Ababa and Adama was completed, cutting travel time from three hours to one hour. Although, the biggest impact on the lives of ordinary Ethiopians was the completion of the Addis Ababa light rail network, offering an alternative to exorbitant prices and the usually run-down minibus taxis and buses.

Some of the most dramatic development is focused on Addis Ababa, which is not surprising as the capital – with its 3.3 million people – is by a huge margin the largest city in the country. The World Population Review suggests that the second-largest city in the country is Dire Dawa with only 252 000 people.

Chinese involvement in the infrastructure programme has been significant but not exclusive. An Italian firm, Salini Impregilo, has been the primary contractor for the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance dam. The same company has completed a much smaller hydro-electric dam on the Omo river, which feeds Kenya’s remote Lake Turkana, and which began generating electricity in 2015.

With the infrastructural building blocks of an industrial economy in place or nearing completion, Ethiopia is eager to attract foreign investment. The present massive public expenditure on infrastructure will be unsustain-able unless it leverages strong private sector growth. Ethiopia published its second five-year macro-development plan, the Growth and Transformation Programme in October 2015. The most significant element of the plan is growth of the manufacturing sector, which it plans to expand by 24% by 2020.

There is thus particular interest on the part of the Ethiopian government in minerals, which will feed into economic growth. Much of the past foreign interest has been in the country’s gold sector, with 170 exploration licences issued for the industry by 2016. But other minerals are being developed too. In 2017, Premier African Minerals, a company listed on London’s Alternative Investment Market, raised further investment capital for its potash mine in the Danakil desert. Potash is a potassium-rich mineral used especially in fertilisers. The country’s first coal mine, a US$116 million venture at Delbi started production in 2011 with the backing of Indian capital.

It is early days yet for the Ethiopian mining industry. However, its development is critical for the country and the government is in the process of putting all the right policy and regulatory structures in place.

Further exploration is happening every day. This combined with Ethiopia’s development strategy and its emphasis on private sector investment and developing free markets is opening up historical opportunities.