Mining involves digging and disturbing the ground but the figurative playing fields are being levelled for women in the mining sector as modernisation shifts the required skill sets away from rock drills to the keyboard and mouse. Training and mentorship initiatives specifically geared at women, combined with broader efforts towards ‘responsible mining’, are also making a mining career more attractive to women.

Charmane Russell, spokesperson for the Chamber of Mines of South Africa, sees ‘significant opportunities’ opening up for women in a modernised mining sector, especially in the country’s deep-level gold and platinum operations, which are going to be less labour intensive and physically arduous. ‘As mining becomes more mechanised, physical strength and stamina will become less important than fine motor skills, dexterity and problem solving; all of which are more easily acquired by new entrants to the workforce.’

AngloGold Ashanti vice-president of group communications, strategy and business development Chris Nthite says that despite significant downscaling, the country’s largest gold producer remains committed to recruiting women into its training programmes and improving the representation of female employees who are being retained in the workforce. ‘Issues of women in the workplace, diversity and inclusion feature prominently in our various training programmes, from induction right through to leadership training programmes.’

Nthite explains how multi-skilling and the learning of new competencies will gain importance in a more mechanised workplace. ‘Many of the innovations in creating the mine of the future are aimed at “remote” mining. A great deal of focus is placed on behavioural skills, including providing individuals with the ability to manage themselves and their relationships with others optimally.’

As employees are being removed from high-risk and underground workplaces, female miners could eventually find themselves on par with male colleagues, competing in terms of skills rather than physiological factors. Significant progress is already being made.

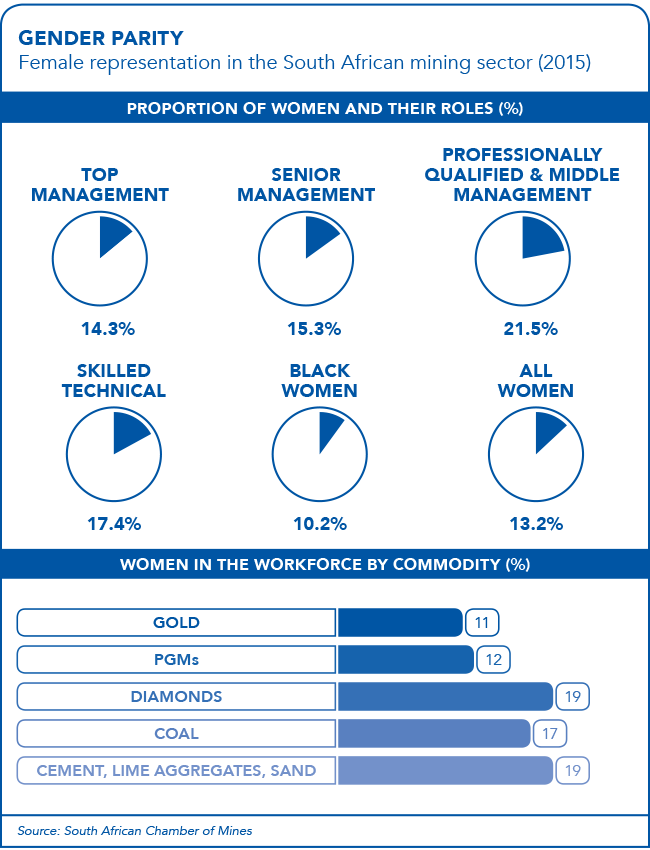

The number of women in South African mining has increased fivefold: from a very low base of 11 400 in 2002 to 53 000 by the end of 2015. Approximately 13% of people working in the South African mining industry are female. The latest available Chamber figures show that in 2015 women represented 14.3% of top management; 15.3% of senior management; 21.5% of professionally qualified people; and 17.4% of those with technical skills.

While many women are working at grassroots levels as operators and also in technical positions (as geologists, chemical engineers and mechanical engineers), these specialists are not converted into senior management and executive roles, according to Deshnee Naidoo, CEO of Vedanta Zinc. ‘We need to start showing women in technical positions [how] to think broader, that you can make the switch into more general management position and then ready yourself for the C-suite.’

The latest draft of the contested Mining Charter calls for just that, setting the following targets for the higher rungs of the career ladder: a minimum of 30% black women in senior management positions, 38% in middle management and 44% of black females in junior management.

‘Women are just as capable as men,’ says Lindiwe Nakedi, Women in Mining South Africa (WiMSA) chairperson and MD of drilling exploration company Gubhani Exploration. ‘Business systems don’t care about your gender – what’s important is that you’re competent and get the work done. But mining is still a man’s world, and although attitudes are shifting, it’s mainly men who make the decisions.

‘Women not only have fewer opportunities but often lack the confidence to stand their ground and make pertinent business decisions.

‘As a result, they tend to be extremely qualified before even applying for a position in mining, whereas men just go for it and then learn on the job.’

The international Women in Mining (WiM) organisation, which promotes female industry participation through mentorship, training and networking, underlines that the gender gap (and wage gap) in mining isn’t just a women’s problem but a wider business issue.

In 2017, WiM UK, in collaboration with professional services firm EY, published a report titled: Has Mining Discovered its Next Great Resource? ‘Women’s advancement and leadership are central to business performance and economic prosperity,’ it states. ‘Profitability, return on investment and innovation all increase when women are counted among senior leadership.’

Across the country, women in mining initiatives are popping up – be it at the Chamber, the University of Johannesburg and, tentatively, the University of Pretoria, or at the mining houses themselves.

‘We have established a WiM committee with the objective of representing women in mining at various levels,’ says Sihle Maake, group communications manager for Harmony Gold. The committee works on issues such as ‘providing input into policies that are gender sensitive, specifically identifying factors that impact women and men differently; facilitating a safe working environment, conditions and protection from hazardous material and disclosing potential risks, including reproductive health; influencing workplace policies and programmes to open avenues for development of all women across business units; facilitating opportunities for formal and informal mentoring; and identifying and removing barriers that may hinder the mobility of women into positions of significance’.

Harmony notes that for the first time in five years, there were more female than male bursary recipients. In 2017, 17 young women and 15 men were the chosen beneficiaries. ‘The Free State, as our host community, remains a key focus area. Over the past five years, 175 – or 70% – of the bursary recipients have come from the communities in and around our mining operations.’

Promisingly, more and more women are enrolling in mining engineering faculties around the country, according to the Chamber. At the University of Pretoria’s Department of Mining Engineering, student demographics have changed, with around 220 undergraduate students in the department, of which 80% are black and 30% female.

‘Comparing this with approximately 70 students in 1997 and an all-white Afrikaans male student cohort, it shows quite a remarkable transition,’ says department head Ronny Webber-Youngman.

‘Although the 30% seems small, it’s still much more compared with other mining universities in the world.’

The School of Mining Engineering at the University of the Witwatersrand used to keep statistics on female versus male student numbers but has not tracked this for the past two years.

When asked where he sees the greatest career potential for women in South African mining, Webber-Youngman says: ‘If you look at the 10 skills needed to thrive in the Fourth Industrial Revolution, they indicate a very strong alliance with “people skills”. The top skills consist of complex problem solving; critical thinking; creativity; people management; co-ordinating with others – group work activities; emotional intelligence; judgement and decision making; service-orientation; negotiating; and cognitive flexibility.’

Nakedi welcomes these developments as she finds women naturally gravitate towards multitasking, working in teams and setting their egos aside in order to reach a mutually beneficial solution.

Above all, she says, there is a need for better communication between the genders. ‘We would love to have men taking part in WiMSA programmes,’ she says. ‘We have to work together, not in isolation or against each other. We certainly don’t want a mining industry without men.’

However, working relationships with male mineworkers are often not easy, especially in core mining jobs, says Russell.

‘The view among many men, including those who would ordinarily consider themselves progressive-thinking, is that women don’t belong underground. This includes those who find it difficult to accept that a woman can be their boss,’ she says.

As women continue to be at risk of being assaulted, raped and even murdered in their mining workplaces, a Chamber-led task team has implemented safety initiatives. According to Russell, these include ‘buddy’ systems, panic buttons, two-way radios, tracking systems, securing vulnerable areas of a mine, sealing off abandoned areas, self-defence training, regular visits by supervisors and an intimidation hotline.

‘The focus is on ensuring that women working in the industry have the same opportunities open to them as men – and that they are confident and safe to pursue them,’ she says. ‘The development and mentoring of women remains a priority for the mining industry.’

As so often is the case, effective change is driven from the top down, where the leadership sets gender diversity targets and embeds them into the business strategy.

Anglo American has been instrumental in this respect and, in 2007, was one of the first mining companies in South Africa to have a female CEO. At present, women hold more than 23% of management positions at the group, accounting for more than 13% of core mining jobs and making up more than 17% of the total workforce.

Other miners are also setting ambitious targets. Sibanye-Stillwater aims to fill 30% of all vacant positions in its operations and management with women.

Meanwhile, BHP Billiton made global headlines in 2016 when it announced its goal of a 50:50 gender balance across all operations by 2025. In September 2017, CEO Andrew Mackenzie reported that it had been a ‘bumpy’ ride but that the company had made more progress in the past year than in the previous 10 years. This was achieved by hiring 1 000 additional women and nearly halving the female turnover rate, in total increasing female representation by 2.9% in the 2016/17 financial year.

‘One of the biggest lessons we’ve learnt is to keep the conversation going,’ he said. ‘Many of our employees needed time to digest such a big change. They needed reassurance the aspirational goal would not disadvantage men.’

While the mining industry will not suit everyone, those wanting to pursue a career should be afforded fair and equal opportunities – regardless of their gender. Even on a level playing field, women should neither be regarded as a weak link nor a threat, but rather as individuals ready to perform their rightful part in South Africa’s mines of the future.

By Silke Colquhoun

Image: Alamy