In 2017, commodity prices began to recover after the difficulties of 2014 to 2016. This was particularly good news for African mining, which has been hard hit by the slump. But once again it highlighted the issue of the regulatory environment in several African countries – and the potential mismatch between this factor and the needs of the industry.

While some countries are in the process of improving their mining legislation – Nigeria and Ethiopia at the fore – there is uncertainty, at best, around ongoing and proposed changes in Tanzania and Zambia, while the continent’s most established mining jurisdiction, South Africa, is riven with disagreement between the industry and government.

The World Bank’s October Commodity Price Outlook predicts a steady yet unremarkable increase in most mining commodities in 2018. The prices of industrial minerals such as lead, nickel and zinc will increase on tight supply and sustained Chinese demand. On the other hand, the bank does expect iron ore prices to continue falling from the US$89 peak it reached in February to below US$60 in 2018.

It has also forecast that prices for South Africa’s two big precious metals – gold and platinum – to recover a little in 2018. But it has to be said that steady Chinese demand for industrial metals has not translated into precious metals. The precious metals basket (gold, platinum and silver, the last of which is not mined on a significant scale anywhere in Africa) has dropped 1% over the course of the past year. The bank is less bullish on the gold price, which it expects to be negatively affected by rising US interest rates, but it is surprisingly positive about platinum. It argues that tighter vehicle emissions regulations in Europe should see autocatalyst demand – the largest component of platinum consumption – remaining robust.

One thing is clear… The big mining firms are once again in a position to invest. Global miners are looking much better off than they did two years ago. They’ve cut debt, disposed of awkward and loss-making assets, and focused on better operational efficiencies.

BHP Billiton, for instance, announced that it had managed to reduce its debt by US$10 billion. Rio Tinto, the least leveraged of the majors, paid off US$2 billion, reducing its debt pile to US$7.6 billion. Anglo American did even better, cutting its debt at the end of 2017 to US$6.2 billion, from US$13 billion just two years earlier.

The big miners are now cash flush. This has been passed on to shareholders in the form of either larger than anticipated dividends (BHP Billiton) or the resumption of dividend payments earlier than expected (Anglo American).

The outstanding question, though, is where and when these strong financial positions are going to translate into capital investment. In other words, when will the mining majors shift from the deeply defensive strategies that have characterised the past two years and start searching more aggressively for growth? And where will they invest?

South Africa, where the enabling environment is in turmoil, is not a strong candidate. The industry and government are still feeling their respective ways back towards a position where they can talk to one another. For all intents and purposes, relations were severed in mid-2017 when government gazetted a new BEE charter for the industry. A poorly drafted document, it raised the bar for indigenous black ownership from 26% to 30%. More than this, it insisted that ‘empowerment’ levels have to be maintained in perpetuity and cannot be allowed to fall below the benchmark should indigenous black shareholders choose to cash out. Against this, the industry has tenaciously clung to the ‘once empowered, always empowered’ position.

The industry believes the charter is both ultra vires – in that the minister does not have the competency to regulate and will not until the much-delayed amended basic legislation, the Minerals and Petroleum Resources Development Act has been passed by Parliament – and that it contravenes South Africa’s Companies Act. The Chamber of Mines has taken the government to court, seeking a declaratory order on the ‘once empowered, always empowered’ issue. In November, however, the Pretoria High Court reserved judgement on the issue.

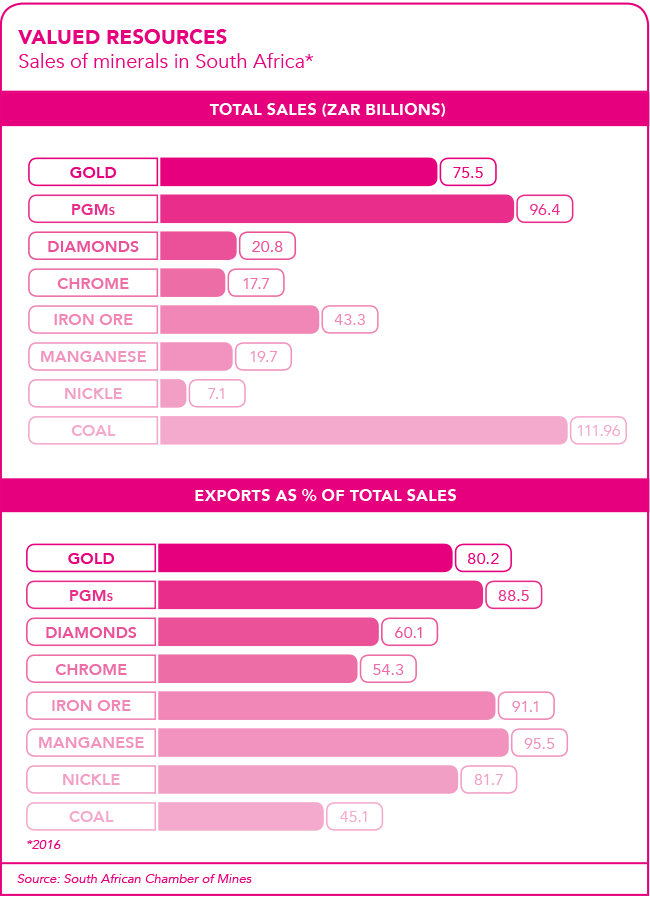

The industry in South Africa faces other headwinds too. At public hearings into a proposal by the state-owned electricity supply utility, Eskom, to hike the price by 19.9%, the Chamber of Mines said this would render 66% of the country’s gold and platinum mines ‘unsustainable’. Its submission argued that companies were reporting an average pre-tax loss of ZAR18 billion across the industry. The deep-level activities of gold and platinum mining – where energy makes up 20% of input costs – would be much more heavily hit than sectors such as coal, where it is just 3%.

Even when the country’s National Energy Regulator limited Eskom’s increase to 5.23%, the Chamber of Mines remained pessimistic. ‘Electricity costs are the fastest growing component of the sector’s cost base,’ it said.

The investment inactivity of the mining majors does, however, correspond to an increase in ownership changes in the South African jurisdiction. Both BHP Billiton and Anglo have sought to immunise their main operations from South African risk, and this has offered opportunities to smaller local firms with coal and platinum assets sold to local firms over the past two years.

In November, BHP Billiton’s wholly owned subsidiary, South32, into which it bundled all its South African assets in 2015, announced plans to exit the thermal coal sector, retaining only its manganese and alumina interests in the country. It intends listing the coal operations in a separate vehicle on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange in 2018. The company has denied that regulatory uncertainty was a factor in its decision, arguing that it is ‘difficult to price’ thermal coal in the long term.

South Africa is not the only African jurisdiction where regulatory uncertainty is likely to inhibit investment. Zambia, the continent’s second-biggest copper producer, has changed its tax regime three times in the past year. Although the World Bank is upbeat about copper prices, the reason it gives is that it expects supply disruptions, and while it does not say as much, some of those disruptions may well come from Zambia.

In 2017, Glencore was forced to suspend operations at its Mopani mine as a result of a dispute with the Copperbelt Energy Corporation over the six-month backdating of electricity tariff hikes. This is not the only occasion in Zambia in the past three years that mining has been brought to a halt by disagreements over electricity tariffs. First Quantum’s mines – including Konkola, the biggest operation in the country – were also down, for the same reason, in 2017.

Although the price has recovered slightly, copper has halved in value since 2011, putting so much pressure on the Zambian fiscus that in October 2015, President Edgar Lungu arranged a national day of prayer for better economic times.

Tanzania has also changed its mining regime recently, amending three pieces of mining legislation in 2017. The purpose of these changes is, according to the Natural Wealth and Resources Act, to obtain a guaranteed return for Tanzania through local ownership and control, and to insist that all earnings be held in Tanzanian bank accounts.

Like South Africa, however, changes to the rules have been accompanied by animosity between the government and mining firms, especially Acacia Mining, which is a subsidiary of Barrick Gold. The company – one of the two big gold miners in the country – has been harassed with employees arrested and a ban imposed on export of copper concentrates (a gold mining by-product) for offshore processing.

Consultants PwC estimate that the higher taxes, new regulations and production shut-downs in 2016 and 2017 have reduced the internal rate of return for the gold mining industry to 18.5%, compared to 24.9% in 2015. Furthermore, it describes Tanzania as the ‘least attractive’ of the African mining jurisdictions it surveys.

PwC’s key ‘takeaway’ from its work on African mining tax regimes is that there is a tricky balance that needs to be achieved between tax, regulation and returns on capital invested by miners. This is not helped when relations between government and industry are as fraught as is currently the case in South Africa and Tanzania.

The problem can, at least in part, be seen as a difference in the pace at which business and governments move. In cleaning up their balance sheets, mining companies have shown an ability to implement dramatic reforms in less than two years. Governments are far slower, which is one of the reasons some African regimes are currently enacting changes that would have been viable at the peak of the commodity price cycle.

In other words they are doing now what might have worked in 2011. However, in the current climate, with companies just starting to look around and think about investment again, such actions carry the risk of being snubbed by the golden goose.