If you look at the mining news from only a year or two ago, we were all prophets of doom as far as the junior sector was concerned. Optimistic words were in very short supply, much like the availability of investment funds or credit for the starving juniors. Publications such as Mining.com ran articles questioning the future of junior miners, and the mood was grim for small explorers, developers and producers around the world.

This was perhaps especially the case for Africa-focused junior mining firms. The continent’s juniors suffered from the same general lack of investment and credit as those in other jurisdictions, but this was compounded by the stubborn and often misguided perception that Africa-based projects are inherently more risky.

However, during the last year, perceptive investors and grateful junior mining companies detected a change in the weather. Money is available and activity is increasing for junior miners globally, and for at least some African companies in particular.

In 2010, as investors worldwide turned to mining stocks as a growth area after the financial crisis, the enthusiasm for junior firms seemed almost excessive – gold exploration firms with prospects in Africa were very attractive in light of the soaring gold price. As a result, there was a glut of easy credit and willing investors.

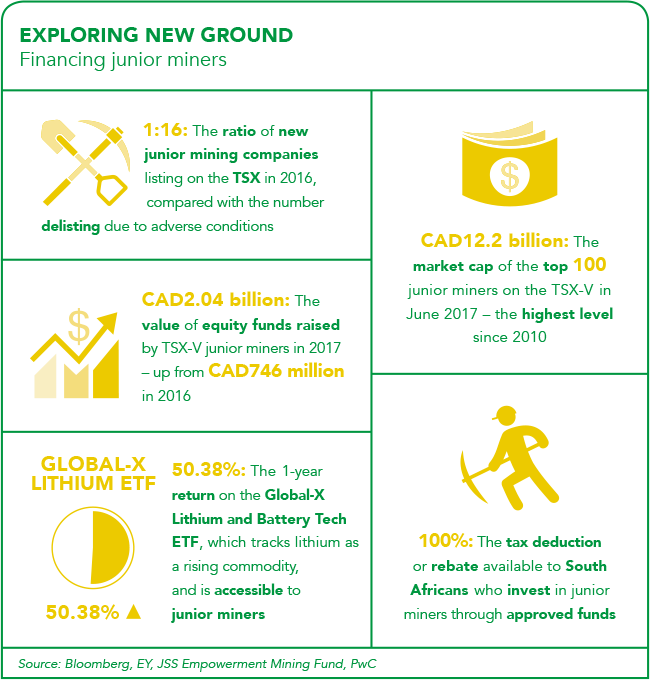

The Toronto Stock Exchange’s ventures sub-exchange, the TSX-V, is one of the most important international barometers of sentiment toward the junior sector, and a number of Africa’s most dynamic exploration and development firms are listed there. In a sign of the market’s exuberance back then, the market cap of the top 100 junior miners listed on the TSX-V rose from approximately CAD8 billion in 2009 to CAD12 billion just a year later – a gain of around 50%.

This situation had been almost completely reversed by the beginning of 2016, when the retreat from junior stocks felt like a near-total rout. According to EY, by early 2016, for every junior company that listed on the TSX-V, around 16 companies were delisted. Similarly, analysts at PwC observed that total equity raised by the junior sector fell by more than a quarter from 2014 to 2015 – and of this remaining amount, around 90% of the available financing went to just 15 particularly attractive junior companies.

In 2016, Deloitte argued that juniors were ‘fighting for survival and trying to feverishly adapt – like plants in the desert, waiting for the rains to arrive’. What a difference a year makes. The 2017 edition of PwC’s annual report on the junior sector is titled Confidence Rekindled. As the company’s analysts note, in 2017, ‘cash poured into the sector as investors embraced greater risk and some of the major mining companies turned to junior players to help replenish their reserves… The rising number of exploration projects, financings, and mergers and acquisitions indicates a renewed confidence in the sector’.

There’s clearly a greater amount of money around. According to the PwC report, TSX-V-listed juniors raised in excess of CAD2 billion in new finance last year, an increase of more than 100% from 2016. But it’s important to bear in mind that PwC’s analysis is for the junior sector worldwide, and is based primarily on the TSX-V – so its conclusions may paint a rosier picture for the African junior sector than is actually the case.

The report notes: ‘Enthusiasm remains selective – a reminder that recovery from the downturn is still a work in progress. The recovery cycle will remain choppy and to a large extent will be driven by commodity prices, although growing demand for electric vehicles, mobile consumer electronics and power storage is creating new markets for old metals.’

Investor attention is still uneven globally, but there are signs that parts of the African exploration and development sector are picking up, and that there’s a rise in general support for juniors in some places. In 2017, the third Junior Mining Indaba took place in Johannesburg – an increasingly well-attended event, which suggests renewed interest in the sector. Speakers at the event highlighted the continued dynamism of West African gold in terms of junior exploration. The indaba also noted the potential value of lithium as a new commodity focus for juniors, given its centrality to various battery technologies.

In South Africa, there are some concerted efforts to support the junior sector, even at a time when the legislative environment seems to be growing less secure. At the beginning of 2017, for example, the JSS Empowerment Mining Fund was launched to make equity investments in junior project developers that have progressed their projects to the bankable feasibility stage.

Investments of this kind – which support junior mining exploration in South Africa – are 100% tax-deductible, provided the investment is held for a certain period. This evidently makes funds of this type an attractive proposition in their own terms. At present, the JSS fund appears primarily to be focused on the coal sector, and it remains to be seen whether it will operate effectively as a broader support for Southern African juniors.

Also in South Africa, the Chamber of Mines now operates a permanent desk focused on supporting what it calls ‘emerging miners’ – small-cap companies that have traditionally been considered juniors as well as a set of even smaller companies that might have previously been neglected by industry representative bodies.

Although the broad-based access to finance that juniors enjoyed five years ago no longer exists, there are still many dynamic and attractive juniors operating in Africa. In Angola, for example, Lucapa Diamond Company is developing an alluvial mine in the country’s Lunda Norte province, which has shown promise for large, high-quality gems. The company is exploring for the kimberlite pipe from which its diamonds originated, and in October it also secured a US$15 million debt financing facility to develop another kimberlite pipe at its Mothae project in Lesotho.

Other juniors too are looking to buy. The AIM-listed Ortac Resources, for example, recently confirmed the acquisition of a controlling stake in Casa Mining, giving Ortac access to Casa’s Misisi gold project in the DRC’s Kivu region. Additionally, Ortac operates exploration and development in Zambia (the Kalaba copper-cobalt project), and in Eritrea (the Haykota VMS copper-gold project).

In East Africa, Tanzania-focused firm Kibo Mining has been developing an interesting mixed portfolio of assets. The company holds access to a large exploration area in northern Tanzania, where it has developed the Imweru gold project, currently the subject of a definitive mining feasibility study after positive earlier exploration results. The company is also exploring for nickel and gold at its Haneti project in the south-east of the country.

Imweru and Haneti are relatively traditional projects for an African junior. But Kibo is simultaneously branching out in a different direction, as proprietor of the Mbeya Coal to Power Project in south-western Tanzania. The project aims to provide fuel to support the country’s national grid, and forms part of what Kibo has called ‘an evolving strategy to re-position as an energy company’. In addition, the company has recently taken a stake in the Mabesekwa Coal Independent Power Project in Botswana, with a similar goal in mind.

Apart from finding good minerals in the ground, this kind of adaptability may be the central requirement for juniors to survive in an African mining environment, where finance is volatile and the regulatory environment can be capricious. Even where legislation may bring a net benefit to a country or mining region as a whole, the burden of adjustment often falls heavily on less-resourced juniors.

As an example, Kibo’s moves toward energy production and away from gold follow the Tanzanian government’s announcement last year, that it would implement a law that increases export royalties, mandates a level of state ownership, and makes contracts easier to dissolve, while also seeking to reduce the scope for transfer pricing and local tax avoidance.

Some of these measures are eminently sensible from the perspective of an African state seeking to make the most of its resource endowment, and larger companies with established mines can often (but not always) adapt.

However, for Africa’s juniors, whose survival usually depends on investors’ uncertain estimations of their future productivity rather than certainties about their proven reserves, any changes to legislation regarding tenure or operating margin can have an immediate and devastating effect.