It is well-known that gold is a refuge for investors during times of doubt. The same, however, cannot be said of the gold mining industry, which comes with a whole range of its own uncertainties. In early 2018, these are especially marked in two of the metal’s most prominent African jurisdictions, South Africa and Tanzania.

The main challenge facing gold miners is not fluctuations in the metal’s price. Indeed, price stability has distinguished the gold sector from other mining commodities in recent years. The metal has traded between US$1 060 and US$1 360 since October 2013, blipping upwards during times of geopolitical tension. Last September, the metal soared to its highest price in a year (US$1 338) after US envoy to the UN Nikki Haley responded to North Korea’s ballistic missile tests by asserting that the rogue state was ‘begging for war’.

Geopolitical uncertainties notwithstanding, no one is predicting radical changes in the price of the metal in 2018. Although pundits suggest this will be a good year for gold – citing higher global growth (which supports demand for gold jewellery), interest rate hikes in the US and Europe, overheated equity markets and increased access to gold through a variety of investment platforms – African gold miners are focused on other issues.

Nowhere is this more the case than in South Africa, where overwhelmingly the issue involves costs and the use of technology to extract ore more efficiently.

The country is of course the world’s most famous gold mining jurisdiction but its sector is now in its autumn years. The combination of old, worked-out ore bodies and significant headwinds in the local enabling environment (notably labour instability, electricity costs and awkward regulation) has seen the country plummet down the league table of gold-producing nations.

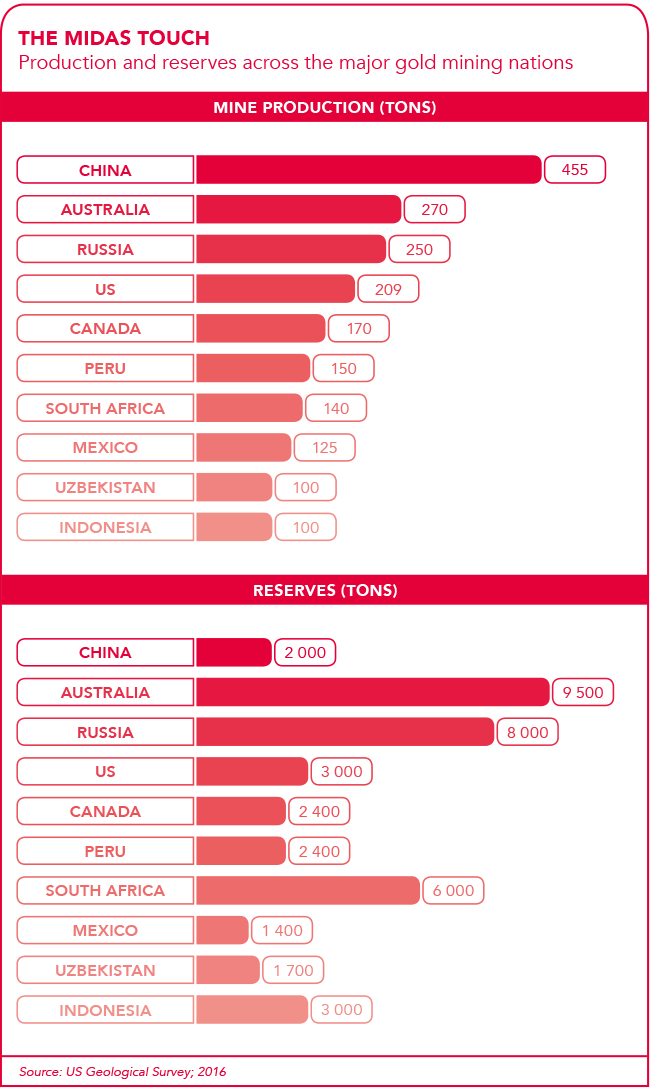

Up until as recently as 2006, South Africa produced more gold than any other nation. In fact, about one-third of the gold ever mined in history has been extracted from the country’s Witwatersrand basin. But in 2007 South Africa was overtaken by China and has since fallen to seventh in the league of gold producers behind (in descending order) China, Australia, Russia, US, Canada and, most recently, Peru. From peak production of 1 000 tons in 1970, output fell to around 130 tons in 2017.

Yet South Africa still has the world’s third-largest reserves of the precious metal, according to the US Geological Survey. South African mineral services parastatal Mintek maintains there is more gold underground in South Africa than has been mined. That said, the last major shaft sinking in South Africa to initiate a new gold mine was Mponeng in 1981, then known as Western Deep Levels No 1 Shaft. Owned by AngloGold Ashanti, Mponeng is one of the world’s deepest mines, with operations extending as far as 3.5 km underground. This fact alone illustrates the main reasons so much of South Africa’s gold resources remain unmined. The problem is the sheer scale of investment required to reach these sorts of depths and extract the resource – it demands a long-term commitment. CEO of Gold Fields Nick Holland argues that it can take 18 years from the discovery of gold to first production.

Gold Fields owns South Deep – a huge asset in the northern Free State, with the longest life expectancy of any South African gold mine (possibly as much as 70 years). It’s the only South African gold mine that was highly mechanised from the outset but is still attempting to ramp up production two decades after opening – with full production still five years off.

It is widely believed that the future of gold mining in South Africa requires a massive application of technology. This is already happening with digitalisation and big data analysis. However, robotics, mechanisation and non-explosive blasting may prove more difficult.

South African platinum miner Lonmin, which faced very similar conditions to gold mining (thin seams, great depths), attempted to retrofit its mines with modern technology in the mid-2000s but failed because the ore bodies it was dealing with required specifically tailored solutions. The same issue has complicated the ramp-up at South Deep.

Mponeng is also an excellent asset. It is expected to produce 450 000 oz of gold per year for at least the next 20 years and at an all-in sustaining cost of US$750/oz. But it’s also AngloGold Ashanti’s last remaining working gold mine in South Africa. The firm, heir to the Anglo American gold mining empire that once leveraged its South African base to dominate the industry worldwide, sold two South African assets in 2017.

Moab Khotsong in South Africa’s North West province was sold to well-established gold miner, Harmony, for US$300 million, while little-known Hong Kong-based operator Heaven-Sent SA Sunshine Investment acquired the loss-making Kopanang mine – located in the same province – for US$7.4 million.

At the same time, AngloGold Ashanti announced plans to place one of the country’s great names in gold mining, Tau Tona (once called Western Deep No 3 shaft), on care and maintenance, possibly as a preliminary to incorporating the remaining assets into the neighbouring Mponeng operation.

These sale prices are cheap, especially in the case of Moab Khotsong, which remains a viable profit-generating mine. But what is especially notable is how pleased market commentators are about AngloGold Ashanti’s retreat from the South African jurisdiction.

Investment bank JP Morgan commented that ‘we regard these disposals as positive for AngloGold … [as] reduced exposure to South African sovereign risk outweighs loss of value’. Meanwhile Goldman Sachs notes that this is a ‘clear strategic positive, as it reduces the South African footprint while also reducing net debt’.

AngloGold Ashanti is the world’s third-biggest gold miner after US firm Newmont and Toronto-listed Barrick Gold Corporation. Neither of these firms hold any South African assets although Barrick is heavily involved in another difficult jurisdiction, Tanzania.

AngloGold Ashanti is the most exposed in Africa generally. Its 17 mines across nine countries include South Africa, Ghana, Mali, Tanzania, Guinea and the DRC.

Holland touches on why the South African jurisdiction is so intimidating. ‘The grade of gold has fallen 3% per annum since 2000 … cost inflation is ever-present [while] incidents of clashes with local communities [rose] 20% per year between 2002 and 2015.’

To this must be added the complete breakdown in the relationship last year between the industry and the South African Department of Mineral Resources over highly prescriptive draft indigenisation (BEE) regulations. This came on the back of a regulatory regime that has become more complex and bureaucratic since 2002, with applications alleged to take anything up to two years.

Two other issues affect South Africa’s older mines. The major operators are putting aside funds to compensate former miners for silicosis, a fatal lung disease caused by prolonged exposure to fine dust in mining. A class action has been allowed by the Pretoria High Court, and it’s estimated there could be as many as 280 000 claimants.

There is also the problem of widespread informal mining, often conducted by former employees who access closed mines to extract the remaining ore. This then introduces an underground network of refiners, middlemen and corrupt officials before surfacing as refined metal in the formal market. Estimates are that there are some 30 000 illegal miners and that production is worth some ZAR7 billion annually. Thousands have died and the government has identified illicit mining as a national threat.

Illicit gold mining also poses a threat in Tanzania. Barrick’s North Mara operation – one of three gold mines the company runs via a local subsidiary called Acacia Mining – has been the scene of clashes between mining security and local villagers who frequently access its premises to search for low-grade rock. Human rights activists claim there have been 65 deaths since 1999. Terrible though these incidents have been, however, they have not threatened the mining company’s existence. That threat has come from Tanzania’s regulators.

After more than two years of pressure from the government – including bans on exports, claims of tens of billions of dollars in unpaid taxes and imprisonment of its employees – Acacia Mining agreed in October 2017 to give 50% of its future returns to the government, in addition to an immediate US$300 million payment.

Gold is the metal of wealth, luxury and beautiful jewellery and sometimes, from the perspective of those associations, is viewed through a romantic haze. However, none of that romance is visible in the gritty and practical process of extracting it from the earth. If anything this process has become tougher in recent years.

By David Christianson

Images: Gallo/Getty Images

Caption 1 A large portion of South Africa’s gold has been utilised for Krugerrand production

Caption 2 Mining majors are rethinking traditional strategies to boost production