A cloud of red dust kicks up as the Komatsu truck leaves Silvergrass mine. It’s hot out here in Western Australia’s dry, remote, mineral-rich Pilbara region, and the sun bakes down as the truck drives away. It’s a huge machine, about the size of a double-storey building, and able to carry 350 tons of material. There’s a sizeable fleet of these vehicles – about 80 in total – moving around Rio Tinto’s five Pilbara mine sites, yet there’s not a driver in sight. Operated by a supervisory system and a central controller located 1 500 km away in Perth, and using pre-defined GPS courses, these trucks automatically navigate the region’s haul roads and intersections, with 45 onboard sensors allowing each truck to keep a constant log of each other’s real-time locations, speeds and directions.

It’s a startling vision of the future, as driverless trucks work alongside human miners to move mining material. But while it may sound like a snapshot of the mine of 2028, it’s the everyday reality of 2018… And, as part of its Mine of the Future programme, Rio Tinto has been running autonomous vehicles in Pilbara since 2008. In fact, the mining giant’s driverless truck fleet moved its 1 billionth ton of material this past January, after passing the 100 million ton milestone in April 2013. Collectively, that autonomous truck fleet has now travelled more than 150 billion km.

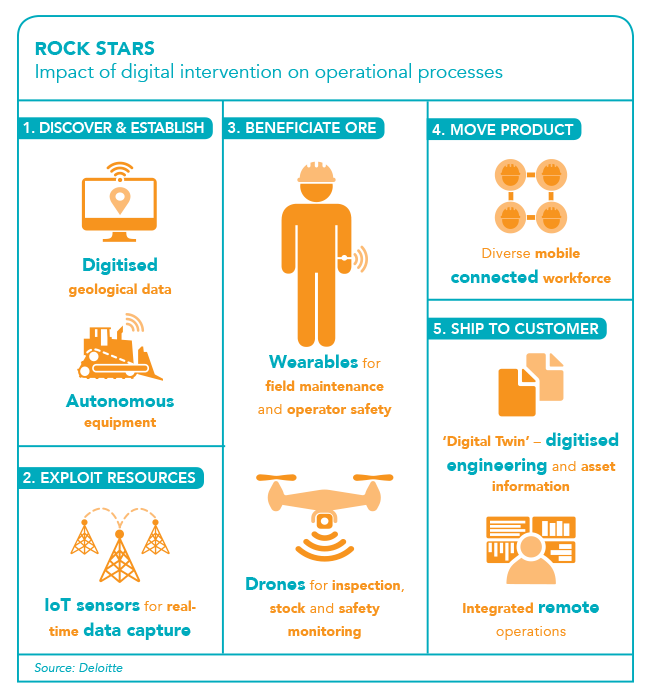

Technology is now the most important principle in mining. From virtual reality interfaces and big data number-crunching to driverless trucks and go-anywhere drones, digitalisation, automation and artificial intelligence are bringing dramatic changes.

As Bold Baatar, Rio Tinto’s chief executive, energy and minerals, told delegates at the Mining Indaba in Cape Town, this February, those new technologies represent the industry’s biggest challenge and opportunity.

‘EY and Deloitte, both rank the “digital revolution” and “digital effectiveness” among the top risks facing the global mining sector,’ he said. ‘But at Rio Tinto we see it as an opportunity. Our industry’s needs are changing. And, in fact, they are changing for the better, for all of us. The composition of our workforce and the skills we need will be transformed irrevocably. Currently, the mining industry employs hundreds of thousands of people. For the large part, this will not change.’

However, Bold continued, the industry will find itself moving from thousands of haul truck drivers to software engineers and data analysts.

‘We will create sophisticated technical jobs, which will require investment in re-skilling,’ he said. ‘This will also make people safer. This will also make operations safer. Currently around two-thirds of our engineers are mining engineers and one-third are data engineers or telecoms experts. In a decade that will have flipped, and the mining engineers will account for around one-third. That means we need to persuade skilled graduates to join Rio Tinto instead of Facebook, Google or Uber.’

It’s a daring statement, placing the mining industry alongside the tech industry in terms of the skill sets needed for the future. What does that future mean for the continent?

‘Africa is the largest untapped source for growth in mining, which will enable a low-carbon future,’ Bold added. ‘And yet, Africa’s greatest resource is its people. With 200 million people aged 15 to 24, Africa has the youngest population in the world. These bright young “digital natives” are perfectly poised to take advantage of the opportunities. The skills that drove Africa’s telecoms boom will drive tomorrow’s mining industry. We need African engineers. We need African technicians. We need African brains. That is the future.’

That future is already rolling out at the University of the Witwatersrand, where Sibanye-Stillwater and the Wits Mining Institute (WMI) launched the Sibanye-Stillwater Digital Mining Laboratory (DigiMine) this past March. A simulated mining environment located on Wits’ West Campus, DigiMine features a vertical shaft in a stairwell, a tunnel and stope in the basement, and a range of communication and digital systems to enable research that will help to create the mine of the future.

The WMI’s DigiMine project aims to make mining safer and more sustainable by harnessing fast-developing technologies and practices from different sectors – which, WMI director Fred Cawood notes, are not always incorporated into mining applications quickly enough to address the industry’s many challenges. According to Cawood, the WMI’s biggest breakthrough has been to forge working links across the university’s schools and research units, thereby allowing mining issues to be addressed in a real-world, integrated way.

‘The WMI now draws upon a formidable battery of expertise and insights from disciplines like architecture, public health, law, global change, population migration, urban development, electronics and computer science,’ he says.

That approach is one that the mining industry as a whole would do well to learn from. According to PwC’s SA Mine report, digital technologies are usually driven at a line-of-business level, which does not necessarily deliver value across the business.

‘A typical example is using drone technology at mine level for pit surveying and mine planning, but not using it more widely for security monitoring (perimeter monitoring), detection of gas emission in the pit, identification of safety transgressions using machine learning, video surveillance ensuring all personnel are evacuated from the pit during blast, or video surveillance of mass protest action outside mine entrances,’ the report notes.

‘Hence, drone systems can be a valuable investment to be leveraged by the mine’s HSSE [health,safety, security and environment] department as well. Often these additional non-core uses of the technology are overlooked, resulting in low return on investment or duplication of effort.’

Speaking at the launch of DigiMine, Neal Froneman, CEO of Sibanye-Stillwater (which is contributing a total of ZAR27.5 million between 2015 and 2020), said the project highlights how important it is for the mining industry to harness the digitalisation that comes with the fourth industrial revolution. ‘The launch of the DigiMine establishes a unique programme that is instrumental for the application of digital technologies in support of safer and more efficient mining operations,’ he said.

Cawood adds: ‘This partnership … paves the way to develop digital technologies that will reduce risk in the mining environment. Safety and competitiveness are cornerstones of a sustainable mining sector, which can contribute to the National Development Plan by reducing poverty and inequality.

‘Our interventions will explore any innovations that can apply real-time digital solutions for reducing mining risk and increasing mining efficiency.’

Again, Cawood emphasises safety. ‘The goal of DigiMine is to take technologies that work outside of mine environments – technologies like GPS, drones or communication technology – and to adapt them so that they can be used effectively underground in order to put distance between people and risk,’ he says.

It’s no coincidence that the move towards the digital mine of the future has come at the same time as an industry-wide improvement in safety levels. As the authors of PwC’s recent SA Mine report note, ‘safety is probably one of the biggest success stories for the mining industry over the last 20 years. In a country where the general safety culture is very weak, as for example reflected in road deaths, the mining industry has done extremely well to reduce fatalities from above 1 000 a year, less than 20 years ago, to the current levels in the 70s’.

The PwC report quotes statistics provided by the Department of Mineral Resources (DMR) that show a downward trend in fatalities for the industry as a whole over the past 10 years, ‘indicating that investments made in safety initiatives by both companies and the DMR are delivering positive results’.

In December the WMI worked with the Wits School of Electrical and Information and the University of Bremen’s Sustainable Communication Networks Laboratory to design, develop and test technology for tracking miners trapped inside a collapsed underground mine. The test was based on a scenario that assumed that the injured and missing miners would not be able to send distress calls. The prototype solution placed small, portable communications devices on the miners, with those devices linked through a series of nodes on a wireless network. The tests confirmed that the technology would work, even if the lost miner was hidden behind a wall of rock or debris.

In a video presentation showcasing the success of the prototype, Cawood’s enthusiasm for his work is clear. What is equally clear is how great an impact digital technology is having on the mining industry.

‘Imagine a mine that’s connected in the same way as on the surface… Where we can position and we can locate and we can see, where you can employ wireless sensor networks to do communication, but to do more – to transfer data in real time to a control centre in order to find people that are missing underground, if they have the correct sensors on them, after a disaster when those people can’t speak for themselves,’ he says. ‘Imagine that mine! That is the mine of the future.’