‘Water has very little value until a mining company’s plant stands still for a day because they didn’t have water,’ says Craig Sheridan, associate professor at the School of Chemical and Metallurgical Engineering at the University of the Witwatersrand. ‘Then suddenly water has great value.’ While the industry has come a long way as far as water management is concerned, there is yet more work to be done, he points out. ‘Mines are definitely moving towards water efficiency, but they need to keep moving forward. Waterless mining – where water is consistently recycled and reused in a closed circuit – is the end goal of being water efficient, but it isn’t possible in every context.’

Peter Shepherd, principal hydrologist and partner at SRK Consulting (Africa), notes that when it comes to water management in mining, an important strategy for mines is the creation of a ‘hierarchy’ of water use, one where varying qualities of water can be put to different uses.

‘This is so that various processes within the mine use water of a quality that is appropriate for the use required,’ he says. ‘Re-circulating and re-using water in this way limits the amount of unnecessary treatment that is needed. This allows the consumption of treated, expensive water to be limited to potable purposes, while other applications like irrigation and plant processes can use water that is less treated.’ The amount of potable water required by the mine, such as for drinking and washing, can therefore be kept to a minimum, he adds.

Graham Trusler, CEO of Digby Wells Environmental, emphasises that mining impacts the quantity and quality of water, effects that are split between groundwater and surface water. He argues that when considering a water-management strategy the key factors to understand and investigate are the potential sources or causes of risks and impacts on the water resources.

‘Water quality impacts usually result from mine waste produced from the mining activity or the mineral processing or from water discharged from old mine workings. These sources usually lead to chemical contamination of the water sources if not managed and mitigated,’ he says.

For Shepherd, the aim of waterless mining is to use only water that can be captured and retained on the mine site. Bringing additional water from outside sources onto the mine to process mineral ore should be minimised. Rainwater, run-off and excess underground water are some of the sources of water that can be collected on the mine. He highlights the reuse of sewage water – which is commonly discharged from the mine site – as one of the first areas where water losses from mines are successfully being reduced.

‘This is because cleaned sewage water can be used in many circuits within a mining and processing operation,’ he says. The collection and reduction in seepage is another, he adds, as the treatment and reuse of mine water is now a common element at new mines, while water that cannot be used by the mine is frequently sent to and subsequently used by neighbouring mines.

The platinum mining sector has made the most noteworthy progress in reusing and recycling water, with as much as 60% of water pumped to tailing dams being returned to plants for reuse. A decade ago, this figure would have been closer to 30%. ‘Mines have become steadily more proactive and innovative in their application of water conservation strategies in the last three to four years, spurred on further by the recent drought,’ says Shepherd.

‘These positive practices are likely to endure, as they have cost-related and environmental benefits that mines now appreciate.’

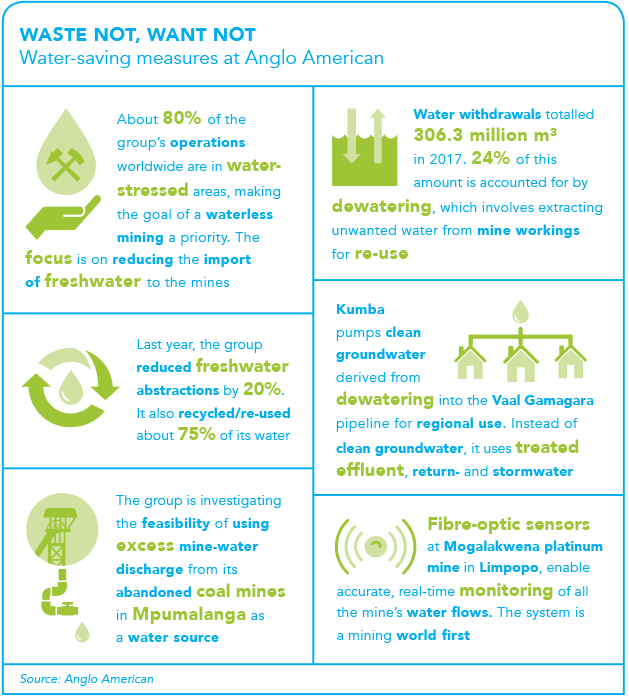

Speaking at the 2017 Mining Indaba in Cape Town, Mark Cutifani, CEO of Anglo American, argued that ‘water availability is a critical risk for the mining industry globally. Approximately 80% of our operations across the world are in water-stressed areas. This is why we are working towards building the “waterless mine”. Through innovative and existing technologies, we are investing in a number of ways to conserve and, where possible, eliminate the use of freshly drawn water from our mining processes. In 2015, of our total operational water requirements, 64% was met by our recycling of water’.

Anglo American’s efforts to eliminate the use of fresh water from mining processes and work towards a waterless mine focus on evaporation measurement and dry tailings disposal, as well as innovative approaches to dry separation and non-aqueous processing. The miner’s closed-loop approach to water dependency delivers greater water efficiencies through direct water recycle and reuse. Today, it meets two-thirds of its total operational water requirements by using a closed-loop system.

Technology also plays a key role. At its Mogalakwena platinum mine in Limpopo, fibre-optic sensing equipment has been installed to enable accurate, real-time monitoring of all water flows across the mine. It is the world’s first permanent installation using this type of distributed sensing technology.

According to Trusler, while water is currently a crucial factor in mining, significant strides are being made towards waterless mining or the closed-loop system. ‘This system requires fresh-water at the start of mining but then moves to a system where water is consistently recycled and reused so that the system is closed. This means less abstraction and discharge, which reduces impacts on quality and quantity of natural resources.’

He adds that while environmental consultants working on water balances for mines emphasise a closed-loop system and are helping mines to achieve this as far as possible, no mining companies have yet achieved such a system, or a dry mine.

Sheridan agrees that no mine can be a completely closed loop. ‘The difficulty is that things build up in closed-loop systems. Eventually you will have a brine forming, which becomes increasingly more concentrated. You need to find a way to get this brine out of the system,’ he says.

Increased necessity for water reporting has also prompted the industry to devise new solutions, says Trusler. ‘Water reporting has become increasingly important and forms part of the planning for many mining clients trying to reduce their footprint,’ he says, citing the CDP (formerly Carbon Disclosure Project) and Water CDP programmes as good examples of this.

‘This has led to companies seeking alternative ways of water management and treatment to reduce the impact on both the environment and their own financial well-being. In addition, governments have started steadily increasing laws, regulations and guidelines for the management of water, though sadly, these are often not properly enforced.’

Trusler notes that among the concepts being implemented are the recycling of tailings water; the use of dewatering volumes to maximum extent before discharge; a reduction in the water demand of mineral-processing technologies and techniques; and the reduction of evaporation. He pegs RandGold and Anglo American as two companies doing particularly impressive things with waterless mining in South Africa and further into the continent.

Sheridan agrees, adding Gold Fields to that list. Although large multinationals are often in the spotlight, they are the ones whose reporting is most accurate, as they follow best practice globally and adhere to a global reporting index, he explains. ‘Because they work in all countries, they follow the legislation that is the strictest globally,’ he says.

Sheridan does, however, point out that while waterless mining is certainly feasible, it should not consume the industry’s focus entirely. The question is whether or not it makes sense, he argues – and the answer is that it might make sense in certain contexts but not in others, because the feasibility of waterless mining is context dependent.

‘If you’re talking about a Canadian operation, for example, I would say it is impossible because it rains so much,’ says Sheridan. ‘If you’re talking about a mine in Namibia, where there is limited to no water, it is certainly possible. A lot depends on what you’re trying to do. For example, if you are mining diamonds it’s a lot more possible because you just need a liquid to separate the diamonds out. If you’ve got a hydrometallurgical process, however, this is very difficult because it has to happen in water.