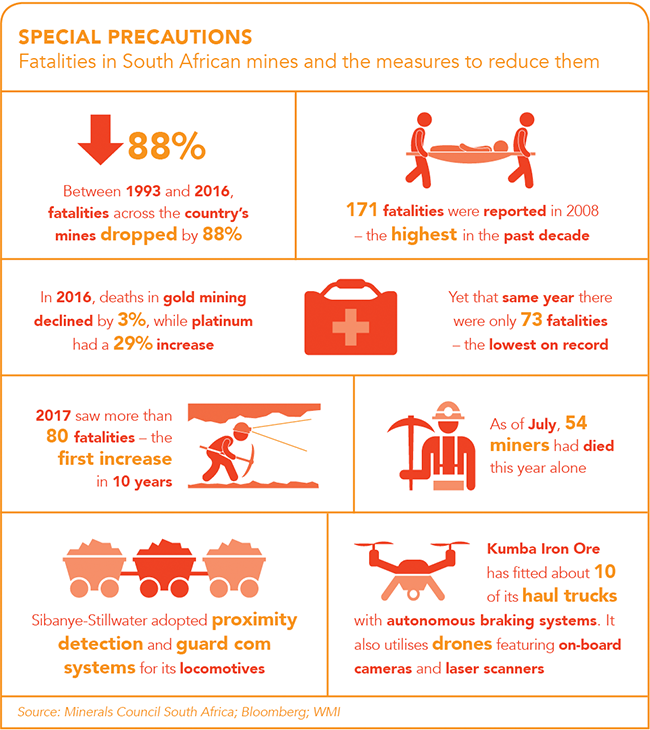

Between 1993 and 2016, there was an 88% reduction in fatalities across South Africa’s mining industry. Yet, 2017 saw a total of 88 fatalities and by end July 2018, as many as 54 mineworkers had already lost their lives. Fred Cawood, director of the Wits Mining Institute (WMI) says the reversal of the long-term positive trend in mine safety is a wake-up call to do more as an industry.

‘In looking for reasons for the increase in mine fatalities, one should look at what has changed in recent years,’ he says. ‘The key factor that stands out for me is the tripartite system, which brought the state, mining companies and organised labour together in the interest of mine health and safety, but which is now broken. The system has its roots in the Leon Commission, which should be regarded as our own mining industry’s “Truth and Reconciliation Commission”. That system is no longer working, and it is showing in the fatality numbers.’

Technology plays a key role in mine safety and has the potential to empower mineworkers to make better decisions on safety-related issues, says Cawood. Technology systems can also help to put distance between mineworkers and risk by navigating them to safe areas, he adds. One of the initiatives on which the WMI is currently working is the Sibanye-Stillwater Digital Mining Laboratory (or DigiMine), a one-of-a-kind entity aimed at putting distance between mineworkers and risk by using digital technologies.

‘The research we are doing falls into four broad themes,’ according to Cawood. ‘The first is research into wireless communication systems for underground connectivity, where the focus is on the design of reliable, multipurpose wireless communication systems for mining that can cope with data flow and storage architecture.

‘The second is surveying, mapping and navigation in the underground environment. The third is health, safety and security, where we work with our leading industry partners in sensor technologies to detect risk.

‘Finally, we do research on system integration for smart mining so that we can provide mineworkers with the right information to make the right decisions at the right time.’

Chairman and principal mining geotechnical engineer at SRK Consulting William Joughin says that in recent years, various technologies have helped make mines safer, such as rock support systems and seismic monitoring. ‘Of course, a mine must adopt these technologies systematically and apply them rigorously if they are to be effective,’ he says.

One of the major benefits of technology use in the mining environment is that it means workers are removed from hazardous high-energy zones, such as the stope face, says Joughin. ‘The necessary advances are more challenging in our narrow-reef ore bodies, however, and considerable research is still required to find practical solutions,’ he says. ‘Success on this front will mark the next step change in safety and will reduce some of the most demanding safety-related requirements for both workers and management.’

According to Marcin Wertz, partner and principal mining engineer at SRK Consulting, there are also many promising digital technologies – both under development and being applied – that will continue to make mines safer. ‘These include the use of photogrammetry and drones to better manage geo-technical risk in surface operations, and the collection and analysis of big data to improve decision-making,’ he says. ‘Advances in communication – especially for underground environments – will also have a positive impact on safety and productivity.’

Cullinan diamond mine, owned and managed by Petra Diamonds since 2008, hopes to gain further improvements in safety, mining efficiencies and productivity through its recent implementation of BME’s AXXIS centralised blasting system (CBS) across its underground operation. With safety being a key consideration, the CBS offers improved control over seismicity (where relevant) and reduces the risk of underground employees coming into contact with potentially harmful gases and fumes emitted by explosives.

Neil Alberts, BME’s product manager for technology and innovation, explains the system. ‘Based on our market-leading AXXIS GII electronic detonator, the CBS allows underground mining operations to initiate blasts from a safe and convenient place on the surface. It also features real-time local monitoring via remote-access monitoring capabilities with cloud-based data storage, greatly improving the pre-blasting and post-blasting decision-making process.’

In terms of the blasting itself, the CBS offers a number of safety features, he says. ‘Each centralised control box is equipped with a unique security key to prevent unauthorised access, and the unit will not fire should a cable fault be detected. Each unit is enclosed in a safe, quality housing that complies with IP65 ingress protection standards, and the system will not fire if there is no uplink between the system components.’

According to Mel Mentz, head of safety, health and environment at Lonmin, the mine has been fatality-free for 13 months. ‘All larger shafts have achieved 1 million or more fatality-free shifts, while our lost time injury frequency rate improved from 4.79 to 4.00 [30 June 2017 to 30 June 2018] – an improvement of 16.5%,’ he says.

In the year that Lonmin achieved one-year fatality-free status, says Mentz, the mine implemented OHSAS 18001, an occupational health and safety management system; various systems to report near-miss incidents; and an action-management tool.

He adds that at Lonmin, technology contributes towards continuous improvement. ‘Technology helps us improve engineering controls to eliminate exposure to fatal risks or to predict failures that could result in harm.’

The mining company supports and implements technology initiatives from the Mine Health and Safety Council, Minerals Council South Africa (formerly the Chamber of Mines), and the International Council on Mining and Metals.

‘Engineering technology examples are leading practices, such as proximity detection systems and noise elimination,’ he says.

‘In areas where we have invested in technology, we have seen a reduction in fatalities, for example netting and bolting, which prevents fall of ground fatalities.’

In 2017, Anglo American announced it had made a three-year, ZAR500 million investment in technology, including using remote-controlled drills at its operations, and drones for aerial surveys. Of this, ZAR6 million was allocated to its subsidiary, Kumba Iron Ore.

Kumba has been fatality-free since May 2016 and shown continued improvements in almost all of its leading and lagging safety indicators. The company’s recent implementation of drones for surveying purposes has removed its personnel from potentially dangerous situations, thus improving safety. Kumba contended with two years of complex legal, governance and logistical challenges to earn an operating licence to fly its own remote aircraft systems over its Sishen mine in the Northern Cape. The drones, which feature on-board cameras and laser scanners, optimise surveying processes in terms of time and coverage, allow easier access to constricted areas, and now undertake routine tasks such as measuring the volume of waste dumps and stockpiles – something previously conducted by surveyors.

In addition, during 2017 and into 2018, Kumba rolled out another technology at its operations – autonomous braking for its haul trucks. This technology automatically brings trucks to a stop to avoid collisions and accidents. More than 10 trucks have already been fitted with the new braking system.

According to James Wellsted, senior VP of investor relations at Sibanye-Stillwater, the miner has adopted a data-driven approach to risk mitigation by employing innovative digital methods to enhance the value of leading and lagging safety indicators and improve focus on critical areas. ‘An example of success in this respect would be the 58% year-on-year reduction in rail-bound equipment related injuries, at the gold operations, which was achieved through this approach,’ he says.

Sibanye-Stillwater’s Kloof, Driefontein and Beatrix gold operations were among the first to adopt proximity detection and guard communication systems for locomotives, at scale. The company now has a full fleet of sub-surface mobile equipment – both rail-bound and trackless – equipped with advanced control systems that have drastically reduced injuries as a result of control and collision-related incidents. The company’s Safe Technology department works to develop and implement fit-for-purpose technologies that will improve safety, with a specific focus on digital technologies.

According to Wellsted, the department has established relationships with several institutions and service providers in this respect, and intends to leverage an innovative ecosystem to accelerate the qualification and implementation of these initiatives. He cites DigiMine as an example, along with initiatives such as personnel tracking and location; predictive environmental exposure mitigation; digital and prescriptive safety management systems; winch signalling; unmanned aerial drones for underground safety inspections; and digital driver behaviour understanding and coaching.

Wellsted adds that as part of its ‘streaming arrangement with Wheaton Precious Metals, Sibanye-Stillwater has committed a further ZAR30 million over a three-year period to fast-track the development and implementation of digital safety technology’.

South Africa’s mining industry advocates zero harm in mines. While it’s certainly a worthy goal, Cawood argues that this will always be difficult to achieve, given the complexities of the business and the extreme environments in which mining takes place in South Africa. ‘I don’t think we must change the goal – we must just become better at implementing and managing it,’ he says. And while more can always be done when it comes to better understanding safety systems, ultimately, more is required than just improvements, he says.

‘We need a step-change. Current technologies do not always perform reliably all the time and, in some areas – such as the prediction of seismic events in mining – the knowledge simply does not exist and must be created through research. In short, the zero-harm objective must remain but be complemented with more training, research and technology development,’ he says.

Wellsted echoes this sentiment. ‘To continue the journey to zero harm, new thinking is required to break through the safety plateau,’ he says. ‘We recognise that zero harm can be achieved but this will require joint problem-solving and sharing responsibility to implement effective solutions.

‘Zero harm involves rethinking and recommitting to building bridges of collaboration between every stakeholder in the mining sector.’