Zambia has been described as being ‘addicted to copper’. The red metal accounts for two-thirds of the country’s exports by value and Zambia’s economic well-being is locked into its prospects. BMI Research points out that copper accounted for more than 90% of Zambia’s mining industry value in 2017. Zambian Chamber of Mines president Nathan Chishimba observed that it was ‘an undeniable fact that when mining does well, other economic fundamentals do well, and thus the opportunities in the Zambian economy expand’.

The surge in international copper prices since mid-2016 is thus extremely good news for Zambia. BMI Research argued earlier this year that it expects Zambian copper production to accelerate, with copper prices staying high and one of the industry’s major bottlenecks – electricity supply – improving. Power outages were common from the beginning of 2015 to early 2017, mostly as a result of the low water levels of the country’s dams. Eighty-five percent of Zambia’s 2 800 MW generation capacity is hydroelectric. The mining industry is the biggest client in the power sector, absorbing 57% of all electricity produced. The situation has improved as the Kariba dam catchment area has enjoyed good rains over the past two years and two new 150 MW units at the dam have come on-stream.

Perhaps more important in the longer term is that Zambia has slashed power tariff subsidies (raising the price 75% in 2017), in an attempt to draw more international private-sector investment into the industry. Potential investors in both renewable energy and nuclear power have expressed interest in the country. Although the copper price is off its June high of nearly US$3.3/lb to around US$2.8/lb (about US$ 6 000/ton), in recent months, it is still well above the US$2 it fell to in mid-2015. The World Bank was expecting copper prices to rise 5% over 2018, despite the negative effects of the trade war between the US and China.

Zambia is currently the second-biggest copper producer in Africa, slightly behind the DRC with which it shares the Central African copper belt. In 2017 Zambia produced 755 000 tons of copper. The ambition of the industry and the government is to get that figure up to a million tons per annum and beyond. Chishimba believes the sector has the potential to grow to 1.5 million tons a year – ‘more than double the 1972 pre-nationalisation production level’. That would make Zambia the world’s fourth-biggest copper producer behind Chile (5.3 million tons [Mt] in 2017), Peru (2.39 Mt) and China (1.86 Mt). Where a country is heavily dependent on a single commodity, as Zambia is, the situation has to be carefully managed. This is an area where many observers have reservations about the Zambian political economy.

More than any sort of ‘addiction’ to copper, it is Zambia’s addiction to debt that is troubling. The country was a beneficiary of the Highly Indebted Poor Countries debt forgiveness programme, which meant that as recently as 2005, the slate was wiped clean and the Zambian government did not owe anything to anyone. By last year, however, the country was in a debt crisis once again. In 2011, when the present ruling party, the Patriotic Front, came to office, Zambia’s total debt was only US$1.9 billion. It has now ballooned out to US$9.4 billion, 69% of GDP, up from US$8.7 billion in December last year. The government has been on a borrowing spree to finance infrastructure in recent years. In the opinion of the IMF, this is unsustainable. Other observers have commented that much of it has been wasted through corruption and elite enrichment. The IMF remains concerned about the direction of play and placed a US$1.3 billion loan to Zambia on hold last August.

Zambia is a ‘victim’ of the surge in credit made available from China in recent years. The China-Africa Research Institute at Johns Hopkins University says that Zambia is one of three African countries ‘excessively reliant’ on Chinese lending (alongside Djibouti and the Congo). One of the problems is that the scale of the debt is unclear – it has been suggested that it makes up between a quarter and a third of the country’s external debt. The need for Zambia to reduce its budget deficit impacts on mining as the government turns to the copper industry to boost revenue. In September it announced a plan to increase mining royalties by 1.5 percentage points across the board and introduce additional charges for metal imports and exports. This is the tenth tax change the sector has experienced in the past 16 years.

The reaction of the industry has predictably been negative. Chishimba argues that ‘higher taxes will not result in more tax revenue. As industry production shrinks, there will be less jobs, less taxes and less money in the government’s bank account’. However, defenders of the tax hike point out that it is indexed against fluctuations in the global copper price. It will be limited if prices fall but an additional 10% will be charged if the metal climbs above US$7 500/ton. Probably more worrying for the big mining companies is tax administration. Earlier this year, Zambia’s tax agency slapped a US$8 billion bill for unpaid import duties on Toronto-listed First Quantum Minerals, one of the four big foreign owners in the copper sector. The figure is more than 70% of the company’s listed value but, it says, ‘does not appear to have any discernable basis of calculation’. The resolution of the issue is being carefully watched by potential investors.

Although some Zambians claim the mining industry has not paid its fair share of taxes in the past, the Zambian Chamber of Mines points out that the government owns part of all four of the main mines in the country (which account for 80% of copper production), in partnership with international investors, and thus benefits when these operations earn a profit. In fact, claims the chamber, government – through its investment holding company ZCCM-IH – is the biggest single shareholder in Zambia’s mining industry. Although the red metal dominates in Zambian affairs, copper is not all there is to mining in that country. Zambia has one big coal mine (Maamba), zinc and lead (Kabwe), as well as more than 300 gold ‘leads’ that are mostly alluvial (panned) but are currently being explored by, among others, the London-listed Alecto Minerals. Alecto has been reported to have identified a small viable open-pit gold mine at Matala.

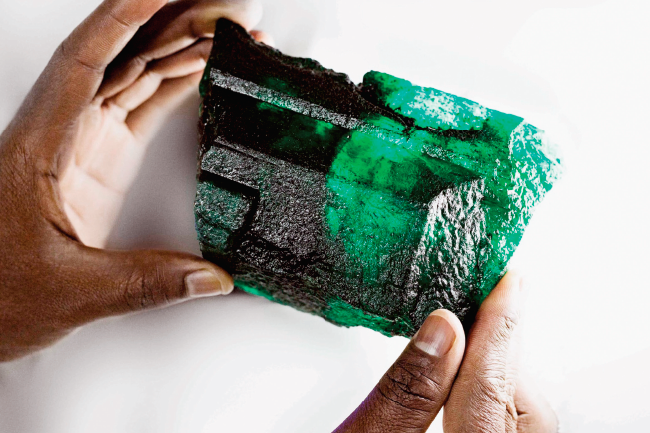

Zambia is also home to some of the world’s finest gemstone mines. Gemfields, owned by South African commodities investment firm Pallinghurst Resources, found one of the biggest ever emeralds (5 655 carats) in 2018. The east of the country – which is part of the Mozambique Metamorphic belt – has also produced aquamarine and tourmaline.

One of the problems facing other minerals in Zambia is that copper has been such a focus of concentration, ever since the first major discoveries in the 1930s, that much of the jurisdiction’s further potential has slipped by unnoticed. Only 61% of Zambia has been geologically surveyed. Among the resources not surveyed are said to be huge, shallow and high-grade copper resources in the north and north-west of the country. Zambia is also a producer of cobalt, now much in demand thanks to its limited supply (mostly from the DRC) and use in lithium-ion batteries used by electric-powered vehicles. Cobalt is usually a by-product of copper mining but the volume mined in Zambia is unknown as it is not separately accounted for.

Zambia’s repeated changes to its mining and especially tax regulations have been criticised. However, governments of the resource-wealthy nations have an obligation to maximise returns for their citizens. Nationalisation (1972) and single party rule (1972–1990) led to a massive decline in copper mined (just 250 000 tons in 2000) with a knock-on effect on political stability. It has to be hoped that the present rising production does the opposite and helps Zambia consolidate its multiparty democracy.