In mining, the real treasures are not immediately visible to the layperson. It takes patience, expertise and various processes until a rough diamond sparkles or gold is extracted from the ore body. In corporate social responsibility (CSR), it’s similar. The projects that deliver lasting social impact for the host and labour-sending communities are not the ones that offer instant gratification and glossy PR opportunities. Instead, they involve difficult, time-consuming conversations between multiple stakeholders, often behind closed doors in rural community halls and drab local government offices.

Yet once in a while, mining companies get their CSR right. Sibanye-Stillwater might be one of them. In September, the gold and platinum miner (together with the Far West Rand Dolomitic Water Association) made about 30 000 ha of its own land available for community empowerment. The land is earmarked for the Bokamoso Barona programme, which will pioneer a large-scale prototype agri-industrial and bio-energy hub in the local municipalities of Merafong and Rand West in Gauteng. This is where a significant number of Sibanye Stillwater’s workforce lives. Most of the economic activity in the area (which is part of the West Rand District) centres on mining, therefore the new hub intends to diversify the local economy and create new income streams for the communities.

The mining company and the water association signed an MoU with their strategic partners, the West Rand Development Agency (WRDA) and the Gauteng Infrastructure Financing Agency (GIFA), committing their combined efforts towards Bokamoso Barona. They’re supported by the Department of Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation (DPME) and the Public Investment Corporation. Up until 2017, several separate initiatives were under way in the programme area. For instance, the Merafong City Local Municipality and the GIFA investigated the feasibility of a bio-energy park with a solar PV farm. Another partnership was involved in Agri-Parks, a programme intended to develop agri-production, processing, logistics, marketing, training and extension services in the local communities, which has yet to operate optimally. Sibanye-Stillwater launched a similar agri-initiative, planning to develop some 15 000 ha in the West Rand District.

In an important milestone, the MoU signatories decided to converge their separate projects into one structured approach and pool their resources to collectively develop the Bokamoso Barona programme. ‘More than four years ago, we had a vision as a company to fully immerse ourselves in the broader regional economic integration of our local economies and communities,’ says Neal Froneman, CEO of Sibanye-Stillwater. ‘The development of sustainable local economies beyond mining is a critical imperative, and it was fortuitous that our agricultural initiative, which we have been working on for some time with the DPME, dovetailed so well with that being developed by the WRDA and their partners. There is still some way to go before implementation and, due to the complexity and scope of this groundbreaking initiative, there will no doubt be significant challenges that will need to be dealt with. ‘As has been highlighted during the debates on land reform, it has become abundantly apparent that successful commercial agri-industrial operations depend on far more than access to land alone. As such, it is heartening to note the level of co-operation and alignment between the partners, which represent serious commitment from business, local government, national government and the investment community.’

The Bokamoso Barona programme intends to deliver on the following points: respond to the needs of the local communities that will secure socio-economic benefits; promote the establishment of black entrepreneurs and industrialists supporting the transformation of the local economy; attract substantial investment from a broad range of commercial and development financing institutions; optimise the value derived through critical resources, most notably land and water; and provide for the active participation of all stakeholders that have a legitimate interest in the establishment and operation of the envisaged agri-processing industrial cluster.

Gauteng MEC for Human Settlements Uhuru Moiloa has already hailed Sibanye’s partnership in an op-ed for the Sowetan: ‘The Bokamosa Barona initiative will be the model the department uses as it talks with companies owning land that can benefit the public. Special focus will be paid to dilapidated mining towns that need revitalisation. Mining towns remain a place of untapped potential that is misdirected into crime and substance abuse.’ Clearly, it’s paramount to develop resilient, self-sustaining communities in order to prevent mining towns from becoming dilapidated. However, as Janine Espin, MD of Economic Development Solutions, points out: ‘Doing this after mines have closed or retrenched workers is like shutting the door after the horses have bolted. ‘Local government leaders need to take lessons from business. Innovation, collaboration, entrepreneurship and business development capabilities are needed. By diversifying early – establishing secondary economies in other industry segments, such as manufacturing, tourism, agriculture, technology, that will sustain communities even after mines have closed, these communities can continue to thrive.‘

Ingrid Watson, programme manager: biophysical environment at the Wits Centre for Sustainability in Mining and Industry, focuses her research on post-mining land and livelihoods. She explains that in the mining sector, corporate social investment increasingly comes in the form of the social and labour plans (SLPs), in which mining houses lay out their commitments towards community development in return for their licence to operate. ‘While there are concerns about the SLPs not being consultative enough and not implemented properly, some mining companies have managed to successfully align their SLPs to mine closure plans and to the municipalities’ integrated development plans,’ says Watson. Bokamoso Barona promises to be such an initiative. Another innovative approach is Harmony Gold’s programme to grow biofuel crops on post-mine rehabilitated land, creating jobs for the local host communities while generating its own renewable energy supply.

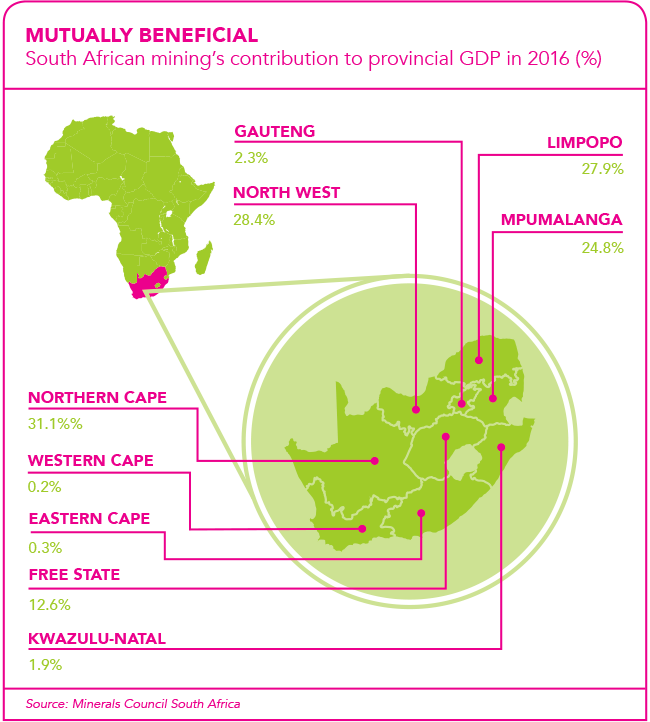

Mining companies carry a huge social responsibility, particularly in developing economies. Despite paying significant taxes and royalties, there’s ‘a demand for mining to give more’, says Nick Holland, CEO of Gold Fields. Speaking at the African Mining Network in October, he said these firms were negatively affected by inefficient and poor local governance because when local governments don’t function, communities look to big business. ‘Communities have found their voice. Nowadays you cannot start exploring in the area unless you’ve spoken to communities,’ he was quoted in Mining Weekly. Gold Fields (which in late-2018, announced plans of cutting around 1 500 jobs at its South Deep mine) has 19 000 employees and another 450 000 people living in the host and labour-sending communities in South Africa, Ghana, Australia and Peru. ‘Those 450 000 people are dependent on us. If we suddenly disappeared, we would be impacting on far more than just 19 000 people,’ says Holland. He was further quoted advising mining companies to assist local governments in building capacity: ‘You might well say, “That’s not our job”, but you should try to help them to help us.’

NGO Mining Dialogues 360° (MD360°) is facilitating this kind of help through the development of an open-data platform that analyses mining-related socio-economic information. ‘Collecting and analysing data is key,’ writes Ross Harvey, senior researcher at the South African Institute of International Affairs, in the Conversation. ‘Too many community engagement forums don’t produce accurate or reliable information. Communities are often fragmented and subject to the problem of self-appointed gatekeepers. ‘Mine-hosting communities need to become shareholders in their own future, and analysing data correctly is key to this.’ MD360° gives community members the opportunity to provide their input and assists mining companies, policy-makers and researchers in understanding the local complexities and making informed decisions. The platform will also offer tools for scenario planning.

Anglo American, a global leader in responsible mining, has developed its own tools to create ‘thriving communities’ through its innovation-led FutureSmart Mining programme. In November, the group held its inaugural Sustainable Development Goals accountability dialogue in Johannesburg. The group has set itself ambitious ‘community livelihoods’ targets (such as creating three jobs offsite for every job onsite by 2025, and five offsite jobs by 2030). In addition, there are similarly impressive targets for improving health and education in the host communities. This doesn’t come cheap: in 2017 Anglo American spent US$88 million on community investment alone.

Getting the socio-economic challenges of mining right will require much more money and effort, difficult discussions and strategic partnerships. But it forms part of the responsible mining journey and is the only way for South Africa’s mining sector to become truly competitive again.