In early 2019, some minerals in the South African mining sector, notably platinum group metals (PGMs) – the second-largest contributor to the country’s mining output – were doing surprisingly well. Labour relations remain difficult although a groundbreaking, pro-mining decision from the Labour Court in mid-March could relieve some of the pressure.

Nevertheless, the industry faces some difficult headwinds. Regulatory uncertainty seemed to be largely resolved when the third iteration of the country’s Mining Charter was gazetted last September.

The charter lays out the BEE standards the government expects from the industry. The representative body of the mining industry, the Minerals Council South Africa (MCSA), initially said it was ‘broadly supportive of its intentions and content’. Now, however, the apparent consensus seems less secure. In March, the MCSA filed an application for a judicial review of the charter and requested that ‘certain clauses’ – related to the charter’s procurement issues – be set aside. Although the MCSA was apologetic and said it had initiated the measure ‘very reluctantly’, it received a blast from Gwede Mantashe, the Minister of Mineral Resources. ‘The [MCSA] never allows stability … there are many among them who thrive on a crisis,’ he said.

These unresolved issues in the enabling environment, however, have not prevented some significant developments going ahead. One of the biggest was Rio Tinto’s announcement that it will be investing ZAR6.5 billion in the next stage of its Richards Bay mineral sands operation. Forty-year-old Richards Bay Minerals produces world-significant quantities of rutile, zircon, titanium and high-purity iron. But grades have been falling and the new investment – into a new mine called Zulti South – is needed to prolong the life of the four mines in the Zulti North lease area for a further 30 years.

The headwinds facing mining go beyond regulation. Early this year, the spectre of unreliable electricity supply raised its head once again, with blackouts for four hours a day (and sometimes more) affecting the entire country. Established miners have a deal with Eskom that allows them to continue operating on reduced power in terms of a 2010 agreement reached after the 2008 crisis – when the parastatal actually ordered mines to evacuate underground personnel – but their situation is hardly sustainable.

Implats spokesman Johan Theron says the company has shifted its energy-intensive operations, including running smelting furnaces, to off-peak times – mostly late at night. But he points out that ‘this is not ideal or sustainable as wear on furnaces is accelerated under these operating conditions’. Plans by mining companies to generate their own electricity from on-site solar PV sources have not gone ahead at the pace originally anticipated. Sibanye-Stillwater, with massive holdings in the gold and platinum sectors, has said the delay was a result of the difficulty in obtaining project finance and red tape related to connecting its plant to the national power grid.

The price of electricity is another problem. The 9.41% increase allowed by the regulator is bad news especially for deep-level gold mining where electricity accounts for 24% of total costs. Gold production had declined for 15 straight months to January 2019 and observers say that most of South Africa’s gold mines are unprofitable at current prices. Combined with an earlier approved increase, which was due to come into effect in April, the price of electricity can be expected to rise 13.81% in 2019. This means a total increase in electricity prices of nearly 400% since the 2008 blackout. The MCSA had previously warned that granting Eskom its full requested 15% increase would render ’95% of South Africa’s gold mines marginal or loss-making within three years’. It called this a ‘death spiral’. MCSA chief economist Henk Langenhoven pointed out that this was not in the interests of Eskom as the state-owned utility would lose 36% of its mining baseload customers.

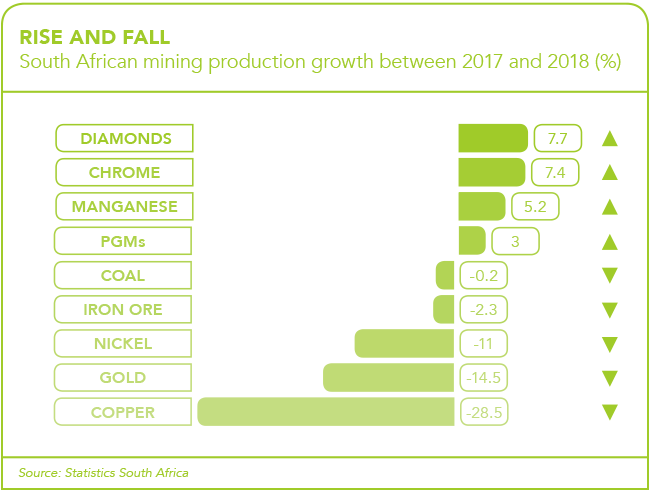

Statistics South Africa data shows that mining output declined in each of the three months to end January 2019. The biggest declines were in gold and iron ore. However, the figures show that PGM production leaped 28.1% in January 2019 – a remarkable surge in a sub-sector that was sunk in gloom less than a year ago.

In mid-2018, two of South Africa’s four big platinum producers, Impala Platinum (Implats) and Lonmin, were cutting back on a massive scale. Between them, they planned to shed 25 000 jobs and Implats had announced the closure of five of its 11 Rustenburg shafts.

Although globally, platinum prices have remained fairly steady, it is the increase in the price of palladium that excites miners. Palladium, which is used in autocatalysts to clean emissions from gasoline engines, has had climbed 60% in price over the year to March 2019 and has tripled over the past three years. The two minerals come from the same source as does rhodium, another platinum by-product. The price of rhodium has increased four-fold since mid-2016. These price surges have seen palladium and rhodium expand their share of the PGM ‘basket’ to 40%, a situation last experienced in 2001.

The short-term global supply-and-demand economics for platinum have not improved. In fact, the World Platinum Investment Council expects oversupply to actually increase in 2019, which can be expected to drive the price down further from its current 14-year low. But palladium is more than compensating. The proportion of palladium varies between mines. Amplats’ gigantic low-cost Mogala-kwena open-cast mine, the largest single platinum operation in the world, is highly geared towards palladium. Sibanye-Stillwater is even better off, with palladium accounting for about half its PGM output, thanks mostly to the nature of the ore body at its US (Stillwater) asset.

The project economics for palladium are sufficiently robust for Implats to plan the opening of a new PGM mine in the Waterberg. This is essentially a palladium operation, with geological studies suggesting it could produce 450 000 oz of palladium per year, compared to just 290 000 oz of platinum. Implats CEO Nico Muller believes the new focus on palladium is here to stay. ‘The change in PGMs is structural, not cyclical, so we are fully confident the buoyant market we see today is going to prevail for the next 10 years,’ he says. The new mine is expected to begin production in 2024.

One of the four big platinum producers, Sibanye-Stillwater, is the main direct beneficiary of a series of Labour Court decisions but the case has implications for the entire mining industry. The issue began with a strike declared by the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (AMCU) against Sibanye-Stillwater’s gold mining operations last November. At the time, AMCU had rejected a three-year wage deal agreed to by the other three trade unions – the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), Solidarity and UASA – in the gold sector, holding out for a bigger monthly increase. The strike ended in mid-April. Along the way, however, there was considerable violence with 60 houses burned down and nine people killed, according to Mantashe.

The minister was once an employee of AMCU’s arch-rival, the NUM, and the striking union has accused him of bias. The NUM, which was displaced by AMCU as the majority union in the platinum sector, is part of the ruling alliance in South Africa, centred on the African National Congress. President Cyril Ramaphosa shares a similar history, having been a founding member of the NUM. These close links have meant that the union has always been susceptible to political pressure and have made it more predictable and willing to negotiate than its newer rival.

Yet, the Labour Court rulings are a considerable blow to AMCU’s power. The first stopped it engaging in secondary (sympathy) strikes in sectors beyond gold mining. The second permitted Sibanye-Stillwater to continue retrenchment processes at two ageing gold mines, despite the unresolved strike. The third ruling, on 20 March, extended the company’s wage deal to AMCU members. Among other things, this casts doubt on the union’s claim to be the majority body in the gold-mining sector.

According to Johan Olivier and Liezl Louw of law firm Webber Wentzel, AMCU’s call for a sympathy strike across the entire mining industry to support its claims against Sibanye-Stillwater in the gold subsector, was the first time that an action such as this had to be considered by a South African Labour Court. It found against AMCU on grounds of ‘reasonableness’.

The provision for ‘reasonableness’, as laid out in the Labour Relations Act, requires that the secondary strike place pressure on the primary employer (Sibanye-Stillwater). It must also meet criteria involving ‘the duration and form of the strike, number of employees involved, their conduct and the magnitude of the strike’s impact on the secondary employer and the sector in which it occurs’, they argue.

Olivier and Louw point out that where these criteria are not met, ‘the secondary strike becomes superfluous, amounting to an exercise in worker solidarity simply for the sake of worker solidarity’. In finding that the union’s call for a secondary strike was not reasonable, the Labour Court set an important precedent, they say. It also spared the mining industry losses in excess of ZAR2 billion.

Mining in South Africa presented an inconsistent picture in early 2019. Yet the enabling environment has improved – as was recognised by a rise in the country’s ranking in the Fraser Institute’s Investment Attractiveness Index (up to 56 in 2018 from 81 in 2017). But headwinds remain strong – especially those related to electricity supply – and the mining industry is going to have to soak up the pressure and ride these out.