Zinc is the world’s fourth-most used metal, behind iron ore, copper and aluminium. Used predominately to galvanise (protect) iron and steel against oxidisation (rusting), it is an archetypical industrial metal. During economic boom times, demand for zinc soars and so does the metal’s price. So, the last bull run for the metal saw it peak at an all-time high of US$4 568 a ton in November 2006.

But the present global economy is much more ambiguous with the trade tensions between China and the US threatening to derail growth. This is reflected in the wide range of forecasts among market watchers with views ranging from extreme optimism – ‘zinc bulls ready to run’ – to extreme pessimism – ‘zinc sentiment staring into the bear pit’. In the last four years the metal’s price has fluctuated alarmingly between a low of under US$1 500 in early 2016 to a high of more than US$3 500 in early 2018. But this was an artificial high brought about by mining major Glencore’s shuttering production precisely in an effort to raise the metal’s price.

Zinc has other industrial uses beyond galvanisation. Zinc oxide is the most important accelerant used in the process of vulcanising rubber tyres. Zinc is used to manufacture brass, aluminium solder and zinc-carbon (household) batteries. Seventeen percent of zinc mined is alloyed with aluminium to produce the dies used to cast components, ranging from toys to engine parts. It is typically found mixed with deposits of lead, copper or silver, which means that on-site separation and smelting processes are invariably a factor in zinc mining.

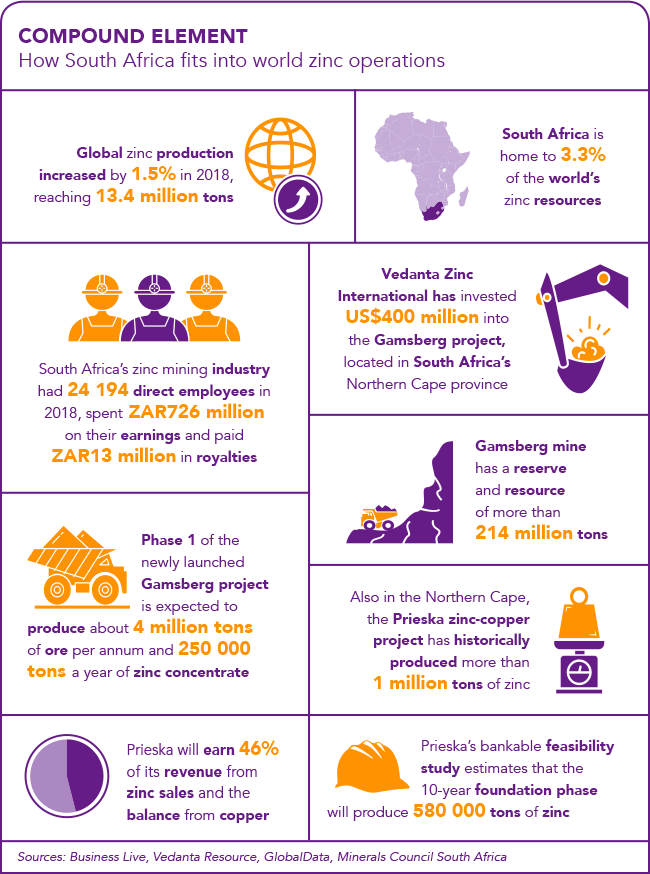

The price uncertainty facing zinc miners going into 2020 is not, however, a major challenge to Southern Africa’s emerging zinc cluster. There are currently four zinc mines in the region, three of them owned by Vedanta Zinc International. The Indian company acquired Skorpion mine in southern Namibia, and Black Mountain mine and the Gamsberg operation, both near Aggeneys in the Northern Cape, from Anglo American in 2011.

Another mine, Rosh Pinah, also in southern Namibia, is owned by Trevali Resources, which acquired the asset from Glencore in 2017. And Australian miner Orion Resources is exploring bringing a fifth mine, in Prieska, also located in South Africa’s Northern Cape, back into production.

All the Vedanta resources are sufficiently closely clustered, geographically, to fuel speculation about an emerging ‘zinc cluster’ involving not just mining but also refining and associated products, such as sulphuric acid and fertiliser. Indeed, there is much excitement about the Gamsberg project, which produced its first ore in January 2018.

At the official opening of the mine in February 2019, Vedanta Zinc International CEO Deshnee Naidoo argued that ‘Gamsberg is so much more than a mine. It is an employer and job creator, an enabler of development and growth [with] the potential to be a catalyst for a new wave of industrial and economic development in the Northern Cape’. Senior South African politicians present, including President Cyril Ramaphosa and Mineral Resources Minister Gwede Mantashe, agreed – although both preferred to see the US$400 million investment as a new beginning for the mining sector in South Africa generally.

The Gamsberg project is the jewel in the crown of the company’s Southern African zinc operations. This opencast mine is a truly world-class asset, with current reserves estimated by the company to be 214 million tons.

Although the deposit was discovered more than 40 years ago, then owner Anglo American preferred to leave it undeveloped while mining neighbouring Black Mountain. The reason for this seeming oversight was the low ore grade (6.5% zinc) and the fact that it was contaminated by manganese. But Vedanta has developed a system that allows it to manage the manganese level in the final concentrate product to bring it below the benchmark 3%.

Gamsberg should have little trouble riding out the current market uncertainty. The total operating cost, according to Vedanta, is just under US$1 000/ton. At present the plan is to send a portion of ore mined to the Skorpion facility for refining. In the longer term, Vedanta has said it intends building a refinery in the area at a potential cost of US$700 million to US$800 million. It is anticipated that it will produce about 300 000 tons of high-grade zinc annually but this is for the future and depends on resolving two uncertainties.

First, a smelter would require an additional 200 MW of electricity, and there are worries about state electricity supplier Eskom’s capacity to bring this on-stream. Second, to make a smelter viable, the transport logistics of the region require a complete overhaul. Production from Black Mountain has been exported via the Sishen-Saldanha railway line, initially constructed as a dedicated iron-ore export route. ‘The situation is not ideal,’ says Naidoo.

She argues that investment by various South African state-owned entities – Eskom, Transnet and the Industrial Development Corporation – is needed if the company’s vision of a zinc-centred industrial complex in the Northern Cape is to be realised.

According to Naidoo, South Africa’s Department of Trade and Industry is ‘keen to use this project to open up the logistics of the region’. She adds that further rail and harbour development is desirable. ‘Our zinc could go out via Port Nolloth or Alexander Bay.’ The obvious candidate port, Saldanha Bay, is fully utilised by iron-ore exports.

The synergies between Gamsberg/Black Mountain and Skorpion mine in southern Namibia are currently strong. Skorpion is a much smaller deposit that has been mined since 2003. It needs to go underground if it is to last much longer and there are plans for this sort of extension. But it does have that valuable refinery, which is already taking zinc-sulphide concentrate from Gamsberg and also smelts ore for Trevali’s Rosh Pinah. It is eager to service other yet-to-be-developed zinc mines in the region. Skorpion and Trevali have a zinc exploration joint venture in Namibia. Vedanta is spending US$160 million on converting the Skorpion refinery to deal with these new ores.

In the same way Vedanta’s Gamsberg project was not a new discovery, Orion Minerals’ Prieska project also represents a revival of interest in a known deposit. Prieska was in fact an active zinc and copper mine in the 1970s and 1980s. It closed in 1991 as a result of falling industrial commodity prices at the time. But that was before the Chinese industrial revolution changed the game. Indeed, Chinese demand in the millennium has inserted a new floor in the market. Although the zinc price does fluctuate, it has not dropped below US$1 000 since Chinese industrial production began to flood the world after 2001. In 2018 China used 47% of the planet’s available 13 million tons of zinc.

Orion recently completed a bankable feasibility study showing what company CEO Errol Smart calls ‘a compelling investment case’. In 1991, the mine produced volumes of zinc and copper that would be easily viable at today’s prices. At its peak, it mined 3 million tons of ore a year, which yielded 1 million tons of zinc and 430 000 tons of copper.

Smart argues that it is the combination of the two metals that makes the project especially exciting. ‘We are in a perfect state. Our zinc is basically subsidised by our copper, and the copper almost pays for zinc production. We are in lowest decile of zinc-production costs, net of copper credits,’ he says.

Global zinc production stood at about 13.4 million tons in 2018. The Gamsberg operation alone expects to reach 600 000 tons of zinc-in-concentrate per annum during the third phase of the project, making it a tier-one zinc mining asset.

To hedge against the many risk factors the mine faces, such as energy and logistics, development will occur in a ‘modal’ fashion, which means that each phase will be capable of paying for itself as if it were a free-standing operation. If all zinc operations in the Northern Cape/southern Namibia nexus come into full production, the region will be producing nearly 1 million tons of zinc every year, making it one of the most significant mining jurisdictions for the mineral.

But there is more at stake than zinc mining. The South African government is eager to prove that the country remains an attractive mining investment destination. The talk around Gamsberg and Prieska has been about demonstrating that development and investment, for both major miners and juniors, is viable in South Africa.

At the opening of the Gamsberg project, President Ramaphosa said: ‘[This] is an important step in our shared journey to revive our mining industry. It confirms our view that […] mining has the potential to be a sunrise industry. South Africa has vast undeveloped mineral deposits that we have the opportunity to exploit for the benefit of all the people of this country.’ The next few years will reveal whether this optimistic view is correct.