Last year will be remembered as the period South African mining shares soared again. There are issues the industry will have to overcome in future but 2019 saw the valuation of South Africa’s 17 listed mining companies almost double. Paul Miller, fund manager with CCP 12J, argues that, ‘there are big success stories associated with South Africa’s platinum miners. The gold sector is doing better on a higher international price. There are also stirrings in coal which, perhaps surprisingly, might have positive implications’.

PwC’s SA Mine 2019, the 11th edition of the annual report, shows that market capitalisation of South Africa’s 10 biggest listed mining companies increased from ZAR482 billion in 2018 to ZAR884 billion in 2019. ‘Gains in commodity prices, aided by a weaker rand, began to bring the industry back into profitability (in 2019)’, it states.

It is in platinum, where South Africa’s four listed producers – Anglo American Platinum (Amplats), Impala Platinum (Implats), Northam Platinum and Sibanye-Stillwater – dominate the global market that the turnaround has been most impressive. Andries Rossouw, PwC Africa energy, utilities and resources leader, says that the platinum group metals (PGMs) producers experienced an increase in total market capitalisation of 129%.

Two years ago, only two platinum miners looked strong: Amplats, which had sold its underground mines to Sibanye-Stillwater, and the tightly run Northam. Sibanye-Stillwater was heavily indebted, Implats was running at a loss and the fifth platinum miner, Lonmin (now owned by Sibanye-Stillwater), appeared to be heading for business rescue.

The turnaround has been remarkable. PwC argues that ‘the most notable performance is that of Implats, which […] more than tripled its market capitalisation to June 2019’. This was an astounding turnaround. In 2018 Implats made a loss of ZAR10.793 billion, making 2018 the fifth successive year it had failed to turn a profit. The company said it was ‘reducing its exposure to higher-cost, less flexible, labour-intensive operations’ – or, as CEO Nico Muller put it, ‘prioritising value over volume’.

In practice this meant reducing the number of shafts it operated in Rustenburg from 10 to six and imposing new cost controls across operations, including those in Zimbabwe.

Implats’ share price has continued to rise since PwC’s SA Mine 2019 was published in September. After opening 2019 at about ZAR35, the counter was trading around ZAR150 in early January. Similar share price runs can be seen throughout the South African platinum sector. Sibanye-Stillwater more than tripled to ZAR40 over the year, while Northam Platinum rose from ZAR41 in January 2019 to ZAR140 in January 2020.

Local efficiency gains are, however, only part of the picture. Another factor has been a weaker rand, a phenomenon that always benefits South African miners whose costs are in the domestic currency but whose revenues are denominated in US dollars. The exchange rate is not a universal panacea to the woes the industry has suffered in recent years. ‘This is not a long-term solution [… but] let’s hope it will help kick-start the industry and even help the economy as a whole,’ says Rossouw.

Probably the most important element of the recovery is the surging prices of palladium and rhodium, previously somewhat marginal components of the PGM basket. Palladium has traded at a premium to platinum last seen in 2001. This has delivered a windfall profit to all of South Africa’s platinum miners. ‘Don’t forget rhodium, it’s been a screamer this year,’ says Miller. Rhodium climbed 140% over the course of 2019, reaching an all-time high of US$6 000 per ton in November.

Benefit has accrued especially to Sibanye-Stillwater, which bought the pure palladium Stillwater assets in the US for US$2.2 billion, taking possession in June 2019. Miller says that ‘with hindsight, this transaction looks prescient’. The Montana mine and recycling assets positioned Sibanye-Stillwater to take advantage of the palladium surge and buy down its previously worrying volume of debt. Both Northam Platinum and Implats have adopted similar North American diversification strategies. Northam bought a recycling firm in 2017, giving it greater exposure to palladium while Implats has made an offer for a Canadian mining company, North American Palladium. In early December, it was reported that the Canadian company’s shareholders had voted overwhelmingly in favour of the ZAR11 billion all-cash offer.

Implats’ Muller points out that the miner has secured its South African base and used this as a springboard to internationalise the company. Under Implats, North American Palladium will remain an operationally distinct entity. ‘We don’t have a very attractive success record of exporting South Africans to head up operations. What is important is that we develop strong alignments and integration between the South African head office, operations and Canada,’ says Miller.

The only South African miner that has not diversified via North America is Amplats. But it already has the most palladium-rich mine in South Africa, the huge open-pit Mogalakwena, located south-west of Polokwane in the Limpopo province. Amplats announced spectacular half-year results in June 2019, with headline earnings up 80% on the previous year. The company was able to pay a handsome dividend (ZAR11 per share up from ZAR3.74 in 2018), returning ZAR3 billion to shareholders. This was the first mid-year dividend paid since 2011. The beleaguered nature of the South African platinum mining industry is shown by the fact that Amplats made no dividend payment at all from 2012 to 2016.

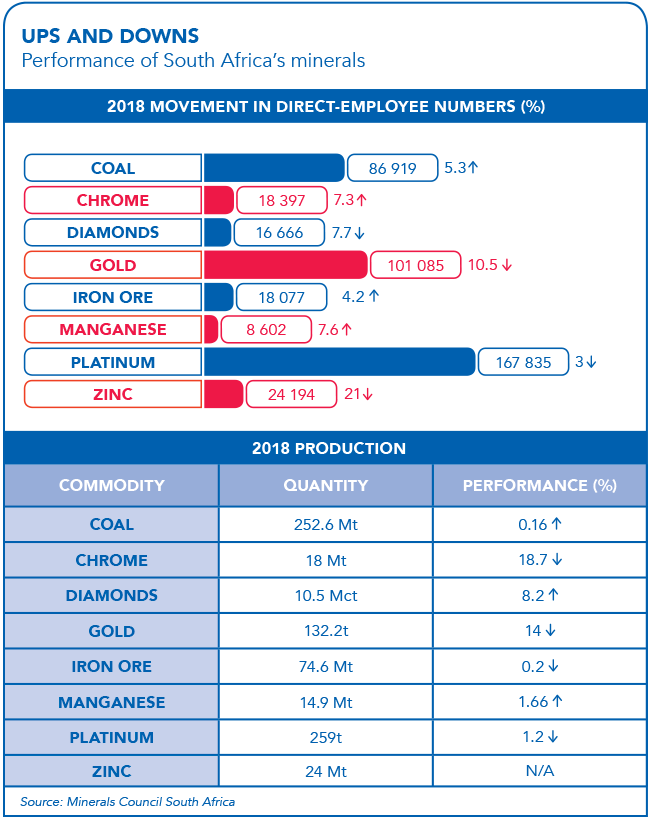

Platinum is one of the four main products of the South African mining industry, alongside coal, gold and iron ore. But, says Rossouw, the sector is undergoing a profound transition ‘from a deep-level, labour-intensive, conventional mining environment to a mechanised, shallower, technologically advanced industry’. Over the past 15 years, overall mining production has declined marginally. A big drop in deep-level gold production has been offset by increased bulk and base-metal production.

The PwC report says that manganese, iron ore and chromium are the only commodities that have seen substantial production growth in this period. Coal remains the single-biggest revenue generator in the South African mining industry, contributing 28% of mining revenues for the year to June 2019.

‘Coal is an interesting sub-sector,’ says Miller. ‘When you take into account the global trend against fossil fuels, it may turn out that coal miners are more inclined to turn to stock exchanges, rather than banks, for finance.’

Miller has a particular company in mind: Seriti Resources. Seriti has been part of a trend where international corporates such as Anglo American and South32 have sold their local coal interests to black-owned South African firms. Seriti, a privately-owned, 91% black-controlled company is the most prominent of these. Formed in 2017 to buy Anglo American’s thermal coal assets, it acquired the huge New Largo deposit (next to Kusile power station) for ZAR850 million in August 2018 and is currently the preferred bidder for South32’s thermal coal mines.

But as Seriti has been growing its asset base, the popular headwinds against fossil fuels have strengthened. Three of South Africa’s four major banks – Standard Bank, First Rand and Nedbank – have announced that they will no longer finance coal-burning power stations. Although their stance on working capital for coal mines is less clear, it may well be that Seriti has no alternative but to list in order to raise capital. This may prove to be a popular listing. Miller points out that the performance of the major listed South African coal owner, Exxaro Resources, has been ‘stunning’ in recent years. The Exxaro counter rose from ZAR40 in January 2016 to ZAR130 in December 2019.

Despite the impressive returns of its listed component in 2019, the South African mining industry is by no means out of the woods. Rossouw argues that ‘investor sentiment and the global attractiveness of the industry continues to erode’. He points out that there has been no new investment in greenfield capital projects for some years now, although Vedanta’s US$400 million investment in a new zinc operation at Aggeneys in the Northern Cape is an exception.

More engagement between stakeholders – companies, investors, financiers, government and communities – is required to secure the future of the industry, says Rossouw. ‘They need to find the balance between stakeholder needs and long-term sustainable operations in their capital-allocation decisions.’