Here’s something new: Imperial College London recently announced the development of a cheap ‘virtual battery’, which generates ‘gravity energy’ by hoisting and dropping weights totalling 12 000 tons up and down Britain’s disused mine shafts. It sounds crazy, but the team behind the project – Scottish start-up Gravitricity – claims it’ll provide clean electricity at half the cost of lithium-ion batteries. It’s also renewable. As Gravitricity MD Charlie Blair told the Guardian, ‘the beauty of this is that this can be done multiple times a day for many years, without any loss of performance. This makes it very competitive against other forms of energy storage’.

The project brings a new element to the mining industry’s growing relationship with renewable energy. The sense at the Energy and Mines World Congress, which took place in Toronto last December, was that the year 2019 was the tipping point that saw renewables becoming the ‘new normal’ at the world’s remote mines. About a dozen new projects were officially announced during the course of the year, with many more either already under development or in the pipeline.

Mining is a notoriously conservative business, so some industry figures are reluctant to take the dive into renewables. During a recent Mining Review webinar, Diversified Energy Holdings director Ian Curry pointed out that ‘while mining executives realise that traditional power options are a challenge, more often than not they say they are “miners” and not “power generators”. […] In my opinion, this exposes mines to an even greater risk because as a result of their lack of understanding of the energy industry, they often fall foul to off-take agreements that are not well suited to the mine’s operational requirements’.

Still, there is certainly an appetite for renewable energy in the mining industry. Speaking at the 2019 Windaba (Africa’s annual wind energy summit) in Cape Town, Gold Fields group head of carbon and energy Tsakani Mthombeni noted that his company was transitioning steadily in that direction. ‘Ten years ago, you would not have heard anyone talk about renewables in mining, but things are changing,’ he told a special session of the summit. ‘Financiers locally and globally are coming under pressure to be seen to be funding low-carbon projects.’

Gold Fields’ carbon emissions are, according to the company, primarily from diesel consumed by haulage trucks and electricity consumption in mining and gold processing. In October, it became the first South African mining company to publish a voluntary report on climate-related financial disclosures, aiming to improve its transparency around climate-related data to investors and other stakeholders. This came after Gold Fields’ June announcement of an AUD112 million investment in an energy microgrid combining wind, solar, gas and battery storage at its Agnew gold mine in Western Australia.

The microgrid comprises five wind turbines capable of delivering 18 MW of power, a 10 000-panel solar farm contributing 4 MW, and a 13 MW/4 MWh battery energy storage system. The grid will be underpinned by a 16 MW gas engine power station and will initially provide between 55% and 60% of the mine’s energy requirements.

The project is backed by the Australian government, with the Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA) contributing a recoupable AUD13.5 million to its construction. That funding is part of ARENA’s Advancing Renewables Programme, with ARENA CEO Darren Miller saying that the project marks a growing shift in the mining sector’s thinking around how it powers its mine sites.

‘The project Gold Fields is undertaking will provide a blueprint for other companies to deploy similar off-grid energy solutions and demonstrate a pathway for commercialisation, helping to decarbonise the mining and resources sector,’ according to Miller.

Rio Tinto is also on the growing list of companies adding renewables to their mines. It recently confirmed a AUD1 billion upgrade to its Greater Tom Price operations in Australia, where it hopes to expand the capacity and life of the mine through a combination of wind, solar and batteries, rather than the comparatively more expensive gas and or diesel usually used in Australian mining operations. According to company statements, Rio Tinto currently fulfils 71% of its power needs from renewable energy sources – although most of that is made up of the large-scale hydro-electric sources that power the company’s smelters in Canada.

Elsewhere, Resolute’s high-tech Syama gold mine in Mali is replacing its diesel generators with a new hybrid power plant consisting of thermal units, battery storage and 20 MW of solar arrays. ‘Identifying and adopting world-class technologies to improve our operations is fundamental to achieving Resolute’s ambitions,’ according to Resolute MD and CEO John Welborn.

‘The new Syama hybrid power solution will lower our power costs at Syama by approximately 40% while significantly reducing our carbon emissions.’

Innovations, renovations and installations such as these are happening across the industry at a rapidly escalating pace, as test cases confirm the cost-saving and future-proofing benefits of renewable energy. When Siemens recently announced its strategic partnership with renewable energy developer Juwi, with a specific focus on microgrids in the mining industry, the company’s Robert Klaffus, digital grid CEO at Siemens Smart Infrastructure, underlined that thinking. ‘Microgrids can bring high levels of reliability and improved energy quality to energy-intensive industries such as mining; and are an attractive alternative when autonomous power supply is needed,’ he said.

‘We are looking forward to the technology co-operation with Juwi on microgrids and believe it will boost the commercial appeal of renewable energy to the mining industry.’

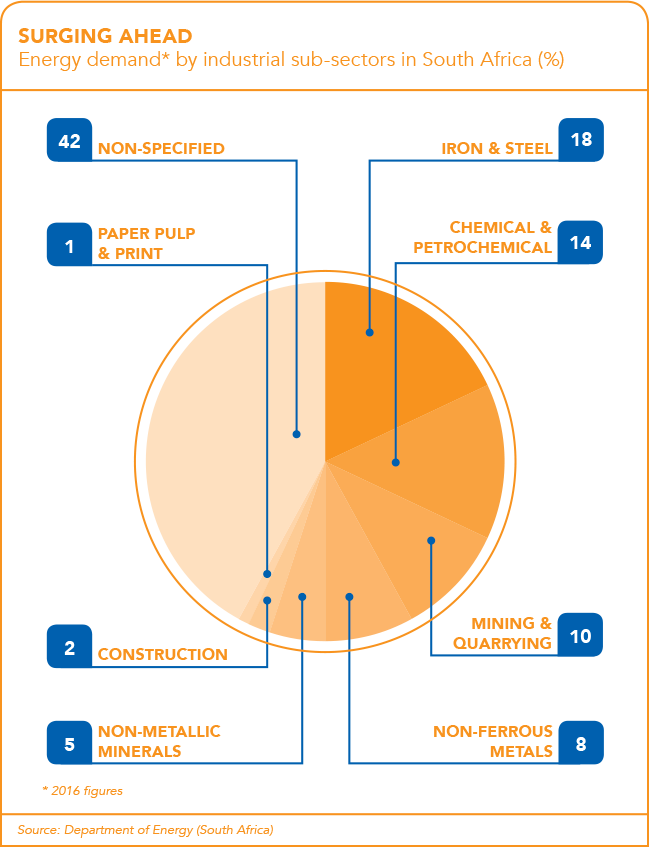

In South Africa, there’s also a growing sense of urgency among miners who need alternative, non-grid energy sources. National power utility Eskom’s power crisis in late-2019 highlighted the issue, as it implemented rotational load shedding that forced mines to temporarily suspend operations.

‘The impact of Stage 6 and Stage 4 load shedding is devastating for the mining sector, as most mining companies will not only lose their week’s production, but this affects the viability of many of these mines,’ says Minerals Council South Africa (MCSA) CEO Roger Baxter. ‘Eskom is essentially making an industrial policy decision to downscale the mining sector when they make these Stage 4 and Stage 6 calls.’

While Mineral Resources and Energy Minister Gwede Mantashe hinted at calling for proposals on filling South Africa’s short-term power gap, energy expert Anton Eberhard (who served in President Cyril Ramaphosa’s Eskom war room in 2015) dismissed the effectiveness of short-term solutions.

‘I’m sceptical,’ he told BusinessLIVE. ‘We tried that in the war room and nothing came of it. Emergency power can be as expensive as US$0.25c per kWh. Other than fast-tracking procurements for the medium term, I believe the most effective policy to relieve short-term energy shortages would be to relax licensing requirements for own generation.’

The MCSA believes that 869 MW of solar power, and up to another 800 MW of conventional power, could be added to South Africa’s national grid by mining companies alone over the next three to four years, with more available from other energy-intensive sectors.

‘Government should stop trying to place all their eggs in the one basket called Eskom,’ says Baxter. ‘We urge government to take decisive steps not only to fix Eskom but also to enable the private sector to bring on stream substantial self-generation capacity. These new self-generation plants would be at no cost to government, the taxpayer or Eskom, and would help provide the room for Eskom to get its house in order.’

The country’s mining companies, meanwhile, are still investigating ways of producing off-grid power, and drawing on increasingly cheaper renewable solutions. Turning South Africa’s – or indeed Africa’s – disused mine shafts into massive virtual batteries may not be practical or possible just yet. But that’s not stopping the industry from considering innovative renewable-energy alternatives.