Demand for manganese is regarded by some economists as the most acute predictor of economic growth among all minerals, for manganese is an essential element in steel making – and steel (along with iron) is the backbone of modern industrial civilisation. The theory is that when demand for manganese increases, the global economy is heading for an upturn. But last year demonstrated that the relationship between growth and demand for manganese is not so straightforward.

In the second half of 2019 the manganese market appears to have tipped into oversupply. China, which produces about half the world’s steel, imported about 15.7 million tons of manganese ore in the first half of 2019, up from 12.3 million tons in the corresponding period of the previous year. This drove the manganese ore price to an all-time high in the early part of 2019 but it has subsequently fallen. In December 2019, Toronto-listed Meridian Mining placed its Brazilian manganese operation on care and maintenance, citing ‘depressed world manganese alloy prices […] since April due to rising inventories in Chinese ports’. The price of manganese concentrates, the company says, declined by 48% over the year.

Low-grade seaborne manganese ore has slumped even further. The price fell from US$6.11 per dry metric ton unit (dmtu) in early 2019 to US$3.3/dmtu at the end of November. While there has subsequently been a slight upswing as Chinese buyers have taken advantage of the low prices, the major manganese market commentator Metal Bulletin, argues that ‘oversupply will remain a headwind’ going into 2020.

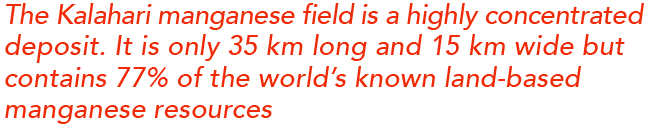

But these headwinds appear to be of little concern to South African producers who continue to ramp up production and look to open new mines. South Africa has the world’s largest manganese reserves. The Kalahari manganese field is a highly concentrated deposit. North-east of Kuruman in the Northern Cape, it is only 35 km long and 15 km wide but contains 77% of the world’s known land-based manganese resources. According to the International Manganese Institute, South Africa mines about one-third of global production. But this figure appears to be out of date and too low.

Some years ago Wits University professor Nic Beukes suggested that South African reserves could ‘fill the gap’ left by falling Chinese mining production. Recent figures suggest this has happened. In fact, the past year has shown that more manganese than ever is being extracted in South Africa.

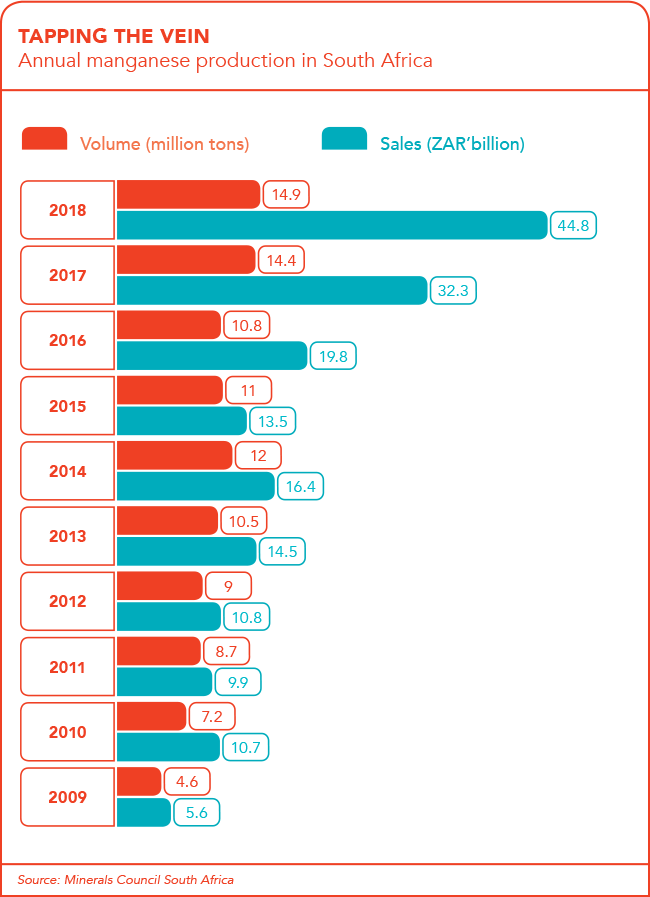

In 2007, South Africa mined 6 million tons of manganese. In 2012 the total production figure was 8.952 million tons. Production then leaped to more than 14.4 million tons in 2017, 14.9 million in 2018, and it was on target to exceed that figure in 2019.

A key demand driver behind this soaring output is the stricter industrial standards imposed by the Chinese government in 2018. Rebar steel is now required to be stronger, and this means more manganese per ton. China’s continuing economic growth is critical to future demand for manganese. Although in 2019, its GDP fell to a 27-year low (6%), this is still sufficient to drive the South African industry. An equally important factor is that South African manganese deposits are highly concentrated (33% to 52%) while China’s industry mines grades of less than 20%.

There are three major manganese miners in South Africa: South32, Jupiter Mines and Assmang. South32, listed on the Australian Securities Exchange with ‘secondary listings on the Johannesburg bourse and the London market’, owns manganese mines in Australia as well as two big operations on the Kalahari manganese belt.

The open-pit mine in the Groote Eylant archipelago off northern Australia is one of the highest-grade pits in the world but is expected to last only another 10 years or so. South32’s South African operations are looking healthy though. The underground Wessels mine has the highest-grade manganese ore (55%) in South Africa. The 50-year-old open-pit Mamatwan mine, west of Kuruman, has the biggest reserves – 433 million tons.

South32 also operates one of two South African manganese smelters, at Meyerton, south of Johannesburg (Metalloys). The other is Assmang’s Cato Ridge operation in KwaZulu-Natal. But the entire South African smelting industry has been hard hit by electricity price increases of 523% since 2006 (with further hikes planned). As a result, only some 20% of South Africa’s manganese production is turned to alloy before exporting; the remaining 80% is exported as raw ore. In 2019, it was reported that South32 was ‘reviewing operations’.

Assmang’s N’chwaning mine consists of three shafts and has the second-largest resource body in the jurisdiction (323.2 million tons) after Wessels mine. It is also of notably high grade (42.5%). The company, which is part-owned by billionaire Patrice Motsepe, also owns Gloria mine at Black Rock (site of the original manganese discovery in 1907). In 2018 Assmang announced it was to spend ZAR2.7 billion modernising Gloria, an initiative that involved a six-month shutdown.

The intention was to double production to 1 million tons per year and is part of the company’s ZAR6.9 billion allocation to expand production in the Black Rock complex. The temporary closure of Gloria mine was largely made up by selling stockpiled manganese in 2019. Nevertheless Assmang’s overall production fell by 8% in 2019.

The third major player in South African manganese space is the Tshipi Borwa open-pit mine, owned by a consortium (called Tshipi é Ntle) consisting of Jupiter Mines (49.9%) and the black-owned local company, Ntsimbintle Mining (51.1%), chaired by Saki Macozoma. Jupiter Mines is listed on the Australian Securities Exchange and numbers among its directors the legendary South African miner Brian Gilbertson, previously CEO of mining giant BHP Billiton. Ntsimbintle also owns 51% of the as-yet unexploited 80 million tons Mokala deposit.

Tshipi Borwa is an extremely modern open-pit operation located adjacent to South32’s Mamatwan mine. In 2019 it exported 3.51 million tons. It claims to be one of the largest and lowest-cost exporters and has a capacity to load ore faster than any other manganese mine in South Africa. The company has invested ZAR2 billion in Tshipi Borwa but has been able to pay its investors extraordinarily well – offering a dividend of ZAR1.1 billion at the end of February 2019.

With South Africa’s manganese mining sector looking like a licence to print money, it is not surprising that other companies are getting involved. Kalagadi Manganese is in the process of ramping up production at its ZAR9 billion manganese mine and sinter plant near Hotazel. Sinter is an intermediate product, of higher content than ore but lower than alloy. The company plans to reach production of 2.4 million tons of ore by 2021/22.

Another new producer is the 51% black-owned company United Manganese of Kalahari (UMK). It produced 3 million tons of ore in 2018 and is currently busy with a ZAR280 million expansion plan. This is expected to lift production to 3.6 million tons by 2021. The privately owned firm is rather obscure but it has said it is considering plans to list, which will shed more light on its numbers.

With South Africa producing such high volumes and exporting mostly unprocessed ore, transport is inevitably an issue. The harbour at Coega, near Port Elizabeth, has a dedicated manganese terminal with a handling capacity of 12 million tons. However, Transnet moved 14.4 million tons of manganese in FY2018 and stated in June 2019 that it expected to move 15.1 million tons in FY2019 (ending March 2020). The difference between this figure and South Africa’s total exports – more than 2.5 million tons – is shifted by road.

The shortfall in harbour capacity means that six different South African harbours are used to export manganese. The commodity is the reason Transnet has started to run the world’s longest train – a 4 km-long, 375 wagon monster – on the line between the Northern Cape manganese fields and Saldanha Bay. But the railway system is close to capacity and even with Transnet planning to increase carrying capacity to 18 million tons over the next three years, future increases in manganese production may be constrained by this factor.

South Africa is endowed with highly concentrated manganese resources, and with demand from China continuing to expand, the mineral looks like a good long-term bet. It is already the country’s fifth-highest earning mineral, behind coal, platinum group metals, gold and iron ore, and it may now be appropriate to refer to South Africa’s ‘big five’ minerals rather than the ‘big four’.