It’s clear that no one is sure how international mineral prices will move in 2023. Hence, uncertainty is the mining industry’s watchword for this year. But the global transition to low-carbon technologies is likely to have an increased impact on the activities of South African miners.

Ernst Müller, senior associate at Herbert Smith Freehills, is bullish about the South African jurisdiction’s future in this regard. ‘We don’t produce all of the most in-demand green minerals but our platinum group metals [PGMs] are going to be massively in demand,’ he says. Müller points out that PGMs are used as electrolysers in creating green hydrogen.

South Africa possesses 90% of world PGM reserves and accounts for more than 70% of global supply of platinum and similarly dominant percentages in palladium and rhodium. Major South African PGM miners have shown every sign of being willing to ride the green wave. For example, Sibanye-Stillwater has invested in lithium projects in Nevada and Finland. Impala Platinum is prospecting for green minerals in Canada and Anglo American has extensive investments in future-facing minerals, notably copper operations in Peru and Chile and operates Mogalakwena, the largest open-pit platinum mine in the world, in South Africa’s Limpopo province.

Ralf Hennecke, SADC MD of BME, which is a member of the Omnia Group and a mining explosives supplier, says he believes ‘the growth trajectory for most minerals, especially those associated with battery technology and broader decarbonisation trends, to be positive into the future’.

Hennecke is positive about all minerals other than those directly associated with carbon emissions. ‘The International Energy Association has predicted that the average amount of minerals needed for a new unit of power generation will grow by 50%,’ he points out. ‘The fact is that solar voltaic plants, wind farms and electric vehicles all require more minerals than their fossil fuel-based counterparts. By 2040, these kinds of applications are expected to be the largest end-users of nickel, overtaking its application in stainless steel, which currently consumes two-thirds of global production.’

In South Africa, one of the main drivers is likely to be the development of a green-hydrogen industry. ‘Green hydrogen is taking off both in South Africa and worldwide,’ says Müller. In South Africa, major corporates as diverse as Anglo American, ArcelorMittal and Sasol have collaborative projects in the green-hydrogen space.

As the global green economy continues to grow, he argues, there will be increased demand for other South African minerals too, including iron ore, manganese, zinc and nickel. South Africa has the world’s largest high-grade manganese reserves. ‘We have a number of headwinds in our local mining economy, notably energy security and logistics, as well as high crime levels. But the world is going to have to keep coming back to South Africa to get these essential green minerals,’ he says.

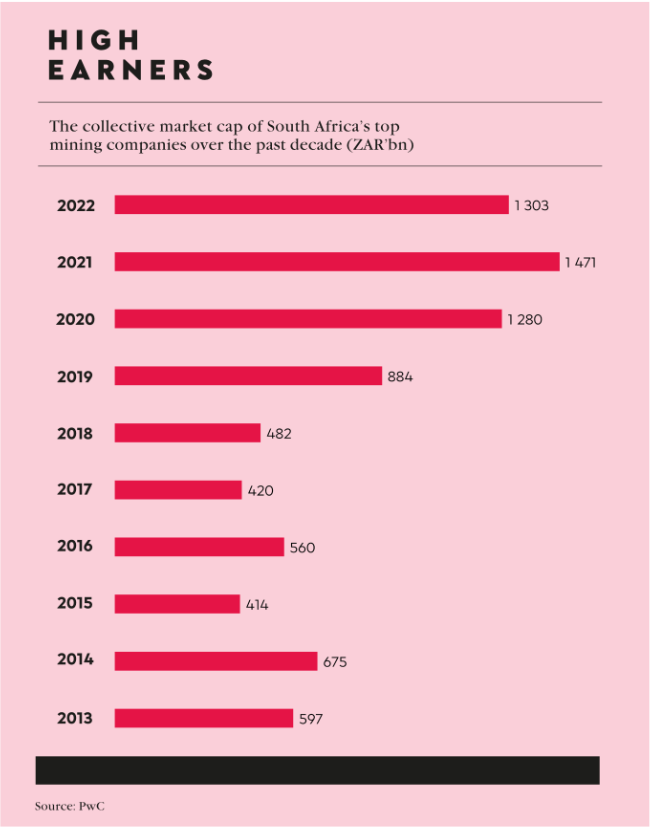

Mining remains a critical element of the South African economy. In 2021 it accounted for more than half the country’s exports by value, according to PwC’s SA Mine report. It will continue to be important in 2023 but is unlikely to bail out the South African fiscus the way it did two years ago. In 2021, the post-COVID surge in international prices put an additional ZAR180 billion into the national fiscus. Such a windfall is not expected by anyone this year.

Commodity prices lost momentum in the second half of 2022, and the developing global economic slowdown suggests the trend will continue well into 2023. ‘It’s not all negative, but South African mining production has been dropping for several years and the headwinds suggest the downward trend will remain in the immediate future,’ according to Müller.

The biggest problem (outside energy) is logistics. Roger Baxter, CEO of the Minerals Council South Africa (MCSA), argues that logistical inefficiencies – copper cable theft, idled locomotives, onerous government procurement rules and vandalism – cost the South African mining industry ZAR35 billion in 2021 and ZAR50 billion in 2022. The biggest loss has been on the dedicated coal line from Mpumalanga to Richards Bay. The Richards Bay coal export terminal has a capacity of 91 million tons/year but in 2021 Transnet could only convey just more than 50 million tons. South Africa’s other main bulk export line, Sishen to Saldanha Bay (mostly iron ore, some manganese) has also operated at less than capacity. According to Baxter, export sales of iron ore in 2022 would have been ZAR16 billion higher if the line had run at full capacity.

Hennecke says that ‘for exporters of bulk minerals, the reliability and capacity of the country’s rail network is a concern. Considerable value has been lost to the economy by curtailed commodity export volumes’.

The essence of the problem is that Transnet needs an injection of private-sector efficiencies as well as capital. The MCSA has long advocated public-private partnerships as the solution to the problem. But South Africa’s two dedicated bulk ore lines are where Transnet makes its money, which reduces the incentive to loosen the parastatal’s grip on these areas.

According to a 2021 presentation by Transnet to the parliamentary portfolio committee on transport, these lines contribute 65% of the rail businesses revenue. The attempt to auction off rail slots in Transnet’s general freight business in late 2022 – which attracted just one bid – is not an encouraging sign for the future. The conditions imposed by Transnet were said to be onerous.

The real problems with logistics is that, like energy-security problems, these systems are not turned around quickly. Hennecke points out that ‘many mining companies have begun augmenting their supply with renewable-energy projects but it is likely to be some years before the benefits of these investments start bearing fruit’.

James Lorimer, mining shadow minister of the Democratic Alliance party, says that ‘embedded energy generation is all very well for big mining companies with established operations and may well work. The MCSA says there’s something like 8 000 MW lined up by the industry, equal to nearly a quarter of current generation capacity. But what about the small miners who cannot afford this sort of expenditure?’.

Energy security is an additional expense for miners operating in the South African jurisdiction. Gold Fields, owner of South Africa’s most recently built major gold mine, South Deep, spent ZAR715 million on a 50 MW solar energy plant. The plant, which was brought into operation in August last year, has about 101 000 solar panels and is expected to meet almost 24% of the mine’s energy needs. Implementation of these sorts of programmes can be expected to continue in 2023.

Despite the headwinds, it’s not all doom and gloom. Müller points out that South Africa is a developed jurisdiction with great strengths. ‘South African mining has a strong future,’ he says. ‘The depth of its expertise is well recognised and it still has considerable mineral resources to be tapped.’

Although infrastructure needs work, the country has skills and institutions that make a difference. ‘Above all, South Africa has the rule of law,’ he says. ‘There is no likelihood of sudden and arbitrary expropriation as has happened in other African jurisdictions.’

Müller stresses that it’s important not to forget about rare earths. One of the world’s highest-grade rare-earths deposits is in the process of being brought into production at Steenkampskraal in the Western Cape. This deposit contains all 15 rare earths.

‘You have to remember that rare earths are critical not just to the green-energy transition but also to modern weapons technology. More than 90% of known deposits are controlled by China. We can expect strong interest in Steenkampskraal from Western countries, especially the US,’ says Müller. But Steenkampskraal is not a new discovery. It was previously operated by Anglo American from 1952.

Müller argues that ‘the rare-earths example begs the question of what else is out there in the South African jurisdiction’. Prospecting is negligible and the main reason, he says, is ‘the shambles’ that is South Africa’s mining cadastre.

‘The department has been vacillating and finger-pointing on this issue for the past 12 years. It has now finally committed to doing what it should have done back then – buying an existing off-the-shelf system – which is what Namibia, Botswana and Mozambique have done,’ he says.

The Department of Mineral Resources and Energy has committed itself to a tight deadline for launching the system (the end of February 2023).

‘We will have to see,’ says Lorimer. ‘The department doesn’t have a good record when it comes to delivery but they do have a new director-general. Perhaps they will surprise us.’