Anybody who’s under any illusions about the dangers inherent in the mining sector should visit the We Care We Remember page on the Minerals Council South Africa’s (MCSA) website. There, in a series of sombre digital memorials, the council lists some of the deadliest events in South African mining history.

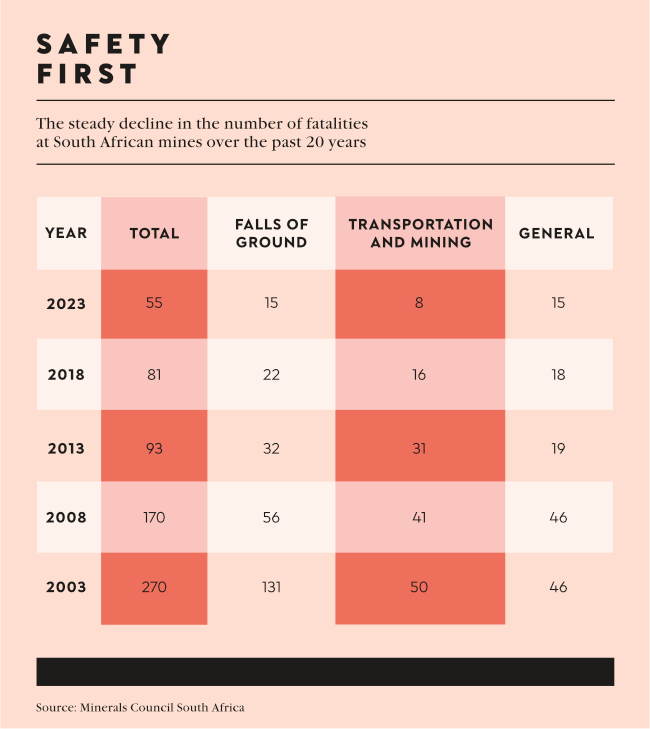

The accounts are horrific. Mponeng, 1999 – 19 dead when a gas explosion tears through an access tunnel 2.7 km below ground. Rovic, 1996 – 20 dead in a fatal mudslide. Kinross, 1986 – 177 dead in an inferno of flames and toxic fumes. Coalbrook, 1960 – 435 dead in a series of cave-ins. The list goes on. Thankfully, though, South Africa’s mines are becoming safer. The number of fatalities has decreased by 88% from 484 in 1994 to 55 in 2023. Similarly, the incidence of occupational diseases in the sector has decreased by 72% since 2014.

‘Today, we have a workplace where there are less airborne pollutants, less noise and generally fewer hazards,’ says Japie Fullard, chairperson of the MCSA’s CEO Zero Harm Forum, pointing to the recent drive towards zero harm. ‘Mining is a far safer place than when we started on this journey. Jointly, with the Department of Mineral and Petroleum Resources [DMPR] and organised labour, we are striving for an inclusive working environment where health and safety are of paramount importance.’

What changed? On the one hand, mining safety equipment has improved significantly with the emergence of digital technologies. On the other, mining companies are more invested in workplace safety now than they’ve ever been.

To the latter point, the industry, together with the DMPR and trade unions, agreed at their recent tripartite health and safety summit on a new set of 10-year goals aimed at achieving zero harm. Technology is, of course, central to achieving that; but the success of any technology ultimately comes down to the people who use it at the (literal and proverbial) coalface.

That dynamic underpinned a recent event held at the CSIR International Convention Centre and hosted by the Mandela Mining Precinct (MMP). According to Michelle Pienaar, manager of the MMP’s Advanced Orebody Knowledge programme, the event aimed to improve geological confidence ahead of the rock face.

‘With “look-ahead” technology, unexpected features and events could be detected and avoided, or additional engineering measures could be implemented to prevent injuries and damage to equipment,’ she said. ‘We have a very powerful opportunity here to help drive technological adoption to propel zero-harm strategies.’

Across the sector, there’s a drive towards human-centred safety technology, focusing largely on AI and robotics.

In one example, UK-based start-up Headlight AI recently developed an imaging and mapping system that uses LiDAR technology and a 360-degree rotating scanner to create virtual maps of mine environments – including movable assets and mining equipment. These digital twins use onboard AI to analyse and identify potential hazards.

‘As a forecast into the future, AI will significantly alter the way mines approach risk assessments, environmental monitoring, impact predictions and training initiatives,’ Kate Collier and Garyn Rapson, partners at law firm Webber Wentzel, write in a recent opinion piece. ‘By using digital twins, virtual environments and simulated scenarios, designated officers can identify potential hazards, and conduct training exercises without exposing personnel to real-life risks. In addition, to minimise operational downtime and identify unanticipated risks to human lives, maintenance teams may assess and inspect a virtual 3D environment before carrying out physical maintenance. Similar to this, 3D environments will be valuable in emergency response and rescue situations to enhance environmental and employee safety before being deployed to unsafe conditions.’

Yet unsafe conditions and near-miss incidents cannot be detected by a single stream of data. To see the full picture, mining environments need multiple sensors, drones and cameras, all connected and speaking to each other in real time. And for that, they need strong and stable networks.

‘Mining in Africa presents numerous challenges and, quite simply, the chances of prospering are limited without the ability to communicate and use cutting-edge technology effectively,’ says Sudipto Moitra, enterprise business GM for ICT at MTN South Africa. ‘The growth of digital communications has filled some gaps, but operating over a public network has imposed limitations. However, these constraints are receding as more mines opt for 5G private networks, which are rapidly changing the face of a demanding sector by offering access to data transfer speeds up to ten times faster than previous standards.’

Moitra says that while 5G private networks are helping miners to maintain high levels of safety, the integration of internet of things (IoT) devices and sensors is further enhancing those capabilities. ‘IoT devices can monitor equipment health, track environmental conditions and provide real-time data on various operational parameters,’ he says.

‘This data can be used to predict efficiency. As the use of IoT devices and sensors increases, predictions are that data transmission will grow exponentially, further driving the need for robust and high-speed network solutions like 5G private networks.’

Wearable technology is an obvious use case. Indeed, people both above and below ground have been using smartwatches, wristbands and the like to monitor their vital signs for many years. But mining-specific technologies are now emerging too. Australian start-up Metasense, for example, recently developed a modular wearable device that attaches to the brim of a miner’s hardhat, enabling mine managers to remotely track the worker’s environmental risks.

Meanwhile, US tech company RealWear worked with i.safe Mobile to develop the Navigator Z1, a set of head-mounted smart glasses that enable remote monitoring. The Navigator Z1 is specifically designed for loud mining environments, using thermal cameras and Android-based voice recognition software that enables fully hands-free use even in 100 dBA noise.

That’s an important feature, and one that highlights the twin challenge of the mining sector – extracting minerals while keeping people safe. MiningTechnology.com, in a small online poll, asked its audience where robotics would have the greatest impact in the mining industry. While 58% pointed to improved productivity, 57% cited safety.

For safety technology to enable the industry’s drive to zero harm, managers, supervisors and frontline workers themselves will have to use it correctly.

Richard Stewart, chief regional officer: Southern Africa at Sibanye-Stillwater, spoke to that delicate balance at the 2024 Mine Health and Safety Summit. ‘We often hear in business circles that culture eats strategy for breakfast,’ he said. ‘You can have the best strategy in the world, but if you don’t have the right culture in your company, you’ll never deliver it.

‘In the mining industry, culture eats engineering for breakfast. You can have the best engineering, but if you do not have a culture that’s going to adopt those critical controls, critical behaviours and critical management routines, it means nothing. That’s the final step that we have to embrace to eliminate fatalities – and it has to be done by all of us, collectively.’