The mining sector plays an important role in the country’s economy. However, it is also a major consumer and polluter of water resources, at times rendering them unfit for other uses. At all stages most mining activities need water, which can even be used as an energy source in some cases. The mining sector is also competing for this scarce resource with other sectors, such as direct consumption, industry and agriculture. In the past, this was not as seriously regarded as it is today, leading to significant legacy challenges related to former – and some current – operating mines.

South Africa is a water-scarce country and recent droughts have exacerbated this scarcity as well as the risks posed by variability in climate, with climate change likely to amplify this variability and further increase the risk of drought. In this context, water needs to be managed with the utmost care to ensure that the needs of current and future generations are sustainably met, and that food security and economic balances are not compromised.

The most severe impacts of mining on surface water and groundwater are in the gold fields of the Witwatersrand and the various coalfields in South Africa, with more localised impacts in the Okiep copper district, located in the Northern Cape’s Namaqualand. Here, mining has exposed sulphide minerals, particularly pyrite, to the weathering effects of oxygen and water, producing an iron-rich, diluted sulphuric-acid solution. This, in turn dissolves other metals, producing an acidic, metal-rich solution, which has the potential to contaminate surface and groundwater resources. These take place in underground and open-pit workings, as well as in waste dumps, creating significant challenges for affected communities and downstream environments.

During the operational stage of mining, this impact can be managed by pumping water out of mines and treating it to a sufficient quality level for reuse or discharge. After a mine closes, funding is often not available to manage these impacts, which can continue for decades or even centuries following the cessation of mining. The state has already spent substantial financial resources in an effort to reduce the adverse effects on contaminated mine water. An integrated and comprehensive action is urgently required from all stakeholders to remediate the effect of pollution.

Through the Council for Geoscience (CGS), the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy (DMRE) has implemented programmes to minimise the impact of mines – particularly legacy mining sites – on water resources.

In the coalfields, proactive risk assessments have been undertaken, using a combination of conventional assessment methods and new methods using AI algorithms to predict areas of greatest pollution risk. This provides management tools for the DMRE to apply in the regulation of the industry.

A passive treatment system is currently being installed on a legacy coal-mining site in the Mpumalanga province. This relies on natural processes and energy sources to treat acid mine drainage being discharged from an old coal mine. Research is also under way to investigate technological interventions to further enhance the efficacy of passive treatment systems for wider applications in affected areas.

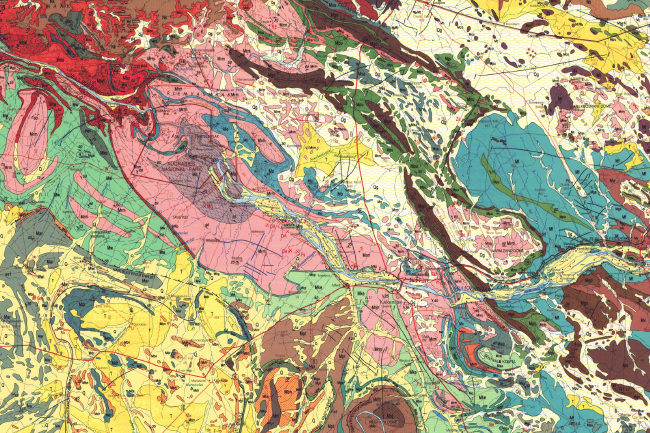

In the Witwatersrand, the old mines of the West Rand, Central Rand and East Rand ceased operations and were allowed to flood. Starting in 2010, a major programme was initiated to prevent the rise of water in the underground mines to a level where they would impact on infrastructure and the environment. Water is pumped from the mines and treated to a quality appropriate for discharge to the environment or reuse. The CGS is engaged in research into the sources of the water that floods the underground workings and developing means to reduce these inflows to lower the cost of pumping and treating the water. This research combines high-spatial resolution mapping, detailed fieldwork and drone surveying, chemical tracer and isotope studies, and hydrological and hydrogeological investigations to identify points and areas of inflow. As an example, a project currently being conducted in the East Rand is aimed at preventing the inflow of up to 5 000 m3 of water daily – this could reduce the operating costs of pumping and treating the water by ZAR25 000 per day.

Traditional risk- and vulnerability-assessment tools have been applied to assess the risk of environmental contamination due to mining. These are well established in areas where data is available and typically developed combining different attributes of an area in linear or simple logical combinations. This has recently been complemented by non-linear approaches to risk assessment, using AI algorithms to evaluate environmental risk and vulnerability.

The CGS has further embarked in the development of a proactive solutions platform towards exploring a scientific approach to understanding the complexities around the coexistence of mining and the environment. This involves using multidisciplinary data sourced from various databases and research materials to create digital layers that, on being related through matrices, are used to generate thematic products. The complexities include exploring driving forces (human activities such as mining), through pressures (emissions and waste) to states (physical, chemical and biological) and impacts on ecosystems’ structure and function. This will lead to management ‘responses’ in the form of, inter alia, measurable indicators and targets.

The process will identify areas where there is potential conflict between the environment and mining. More importantly, the process will explore and highlight preventative and mitigation measures including improved mining methods and technologies that can enable the extraction of natural resources with minimal impact on the environment, thus enabling co-existence of mining and the environment where feasible. It can further help test the legal instruments used in the sector towards effective application, review and amending to ensure sustainable use of all natural resources, all of which is in concert with the aspirations of Section 24 of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa.

The impacts of mining on water and the environment often continue long after operations have ceased. In a recently drafted National Mine Closure Strategy by the DMRE, emphasis is placed on promoting a paradigm shift to concurrent economic diversification in mining areas, where a diverse and sustainable local economy is developed around a mining project, to enable continued economic activity after all mining has ceased. This allows planning for the post-mine-closure management of water, incorporating it into local economic development and regenerative environmental management.

The CGS combines an overall view of South Africa’s mine water-management challenges and priorities to develop solutions that promote sustainable development. These are hoped to reduce both the adverse impacts of mine water and the cost of remediation.