For more than a century, De Beers was the market-maker in diamonds. The company’s long monopoly, from 1888 to 2006, saw it control the supply and hence price of diamonds globally. When diamonds from Kimberley started flooding the market in the 1870s and 1880s, there was a danger for the industry that its product would become so common, it would be little more than another industrial commodity. De Beers was largely responsible for averting this outcome by creating a gemstone market based on the institution of marriage. Its 1980s marketing slogan – ‘a diamond is forever’ – was one of the most successful advertising tag lines in history.

De Beers, however, abandoned its cartel in 2006, under legal pressure from the EU (and following decades of pressure from US anti-monopoly regulators). But it remains the world’s largest producer by value and, through its marketing arm, the custodian of the global gemstone industry. The other major player, Russia’s Alrosa, produces more carats but De Beers produces more high-value stones. The two companies combined account for about 50% of global diamond production.

In January, Alrosa reported a 44% year-on-year decline in sales and De Beers also experienced a drop. The latter holds 10 global sight-holder sales and auctions (known as sights) in Gaborone, Botswana – as well as South Africa and Namibia – every year. But the first two Gabarone sights of 2019 delivered under US$1 billion (its lowest since it first publicised its sales data in 2016). However, the factors driving the dip are short-term problems.

Noted diamond-market commentator New York-based Paul Zimnisky argues that ‘investor sentiment is low by valuation standards projected by future diamond price expectations’. In other words, the international diamond market is going though a phase in which prices are more favourable to buyers than sellers. De Beers itself, in last year’s Diamond Insight Report, attributes this to high levels of supply as a result of three new mines that came into production in 2017.

Rapaport, one of the industry standards, says that rough-diamond production fell 3% in 2018 to 146 million carats. But even that volume, it argues, ‘may be too much for the market to absorb. We [Rapaport] believe the mining companies have over-projected the volume of rough they can sell in 2019, especially at current price levels’.

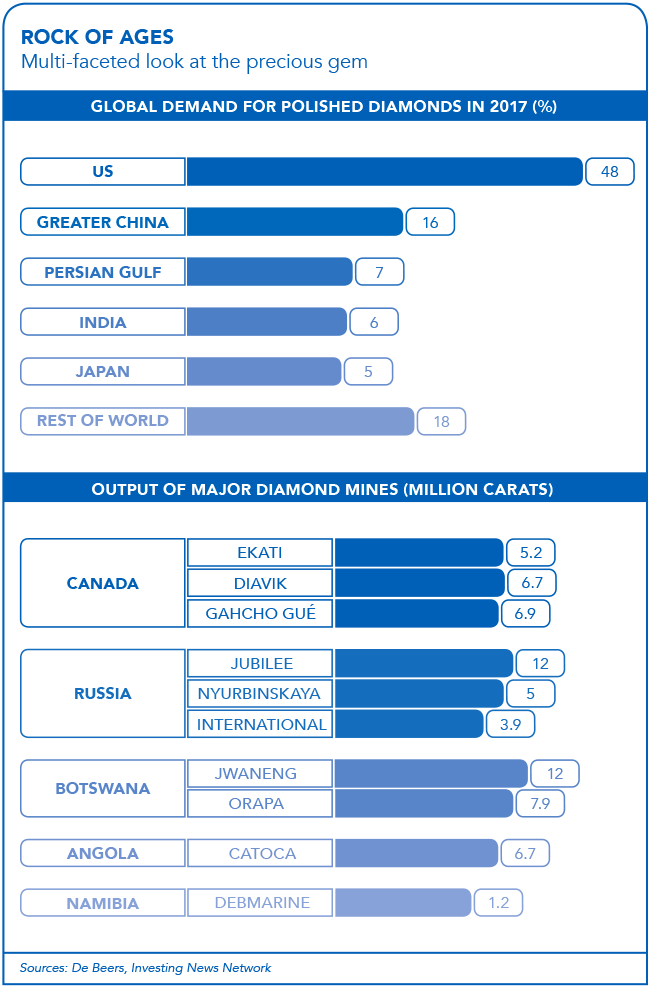

South African diamond consultant John Bristow stresses that demand from China, the second-biggest gem diamond market after the US, has been negatively affected by the current trade war with the Trump administration. ‘The trade war has depressed the renminbi [the official currency of the People’s Republic of China] and that has brought demand down by about 10%,’ he says. But this situation, he points out, is a short-term issue.

The largest of the three new mines is Gahcho Kué in northern Canada, owned jointly by De Beers (51%) and Mountain Province Diamonds (49%). The mine is a true world-class asset, which reached full commercial production late last year and is expected to produce up to 6.9 million carats in 2019. That’s more than De Beers’ only remaining South African asset, Venetia (5.2 million carats in 2017) and more than half the production of the world’s most productive diamond mines, Jwaneng and Orapa in Botswana (about 12 million carats each).

Yet while there are unexploited diamond resources, the number of mines is on a downward trajectory. This can be seen in South Africa where former De Beers assets are not exactly shining at the moment. De Beers sold two big mines, Cullinan and Finsch to London-listed Petra Diamonds. In recent years, Petra has borrowed and invested heavily in both. Yet Finsch’s production has been falling and the expected increase from Cullinan failed to come through on the scale expected, according to Petra’s January report. De Beers announced the closure of another South African mine, the small Voorspoed operation, in the middle of last year, after failing to find a buyer.

Cullinan is, naturally, one of the great names in diamond mining, not least because it is the source of the largest diamond ever found, a 3 106 carat monster. It was extracted in 1905 and cut into several smaller stones that now form part of the British crown jewels. But Cullinan, like Finsch, has also become an old mine with a limited future lifespan. Of course, no mine goes on forever. Zimnisky expects the global portfolio of diamond mines to shrink from more than 50 today to 14 by 2040. That implies a decline in total production from today’s 145 million carats to about 60 million carats. The only million carat-plus mine in development is the Luaxe project in Angola, scheduled to reach commercial production by 2022. It is lab-created diamonds, however, that are seen as the biggest threat to the industry. Synthetic diamonds have dominated the industrial diamond space for some years but now the quality has improved to the point where it takes sophisticated equipment to tell the difference between a natural and a top-quality synthetic gem.

The volume of synthetics is currently a tiny proportion of the total of gem-quality diamonds produced annually – 4 million to 5 million carats versus 73 million carats of ‘naturals’ in 2017, according to Zimnisky. Almost all synthetic production is sold in the key US market, which makes up 48% of the total global polished-diamond market. Synthetics have been selling in the jewellery market at a 30% to 40% discount, despite the insistence of manufacturers such as San Francisco-based Diamond Foundry, that they are a superior product. Diamond Foundry’s website is littered with attacks on natural diamonds for the supposedly negative social and investment impacts of diamond mining.

De Beers is leading an industry-wide process of countering such attacks by certifying ethical natural-diamond supply chains through a blockchain-based system called Tracr. But it is the issue of cheaper synthetics that De Beers is tackling directly through the establishment of Lightbox. Its strategy is almost counter-intuitive – to make synthetics even cheaper. (Lightbox sells synthetic gems at US$800 per carat, a fraction of the cost of mined diamonds, which cost thousands.) It is attempting to signal that synthetic diamonds are little more than costume jewellery.

This is based on a concept known as ‘Zahavian signalling’. The theory is that human evolution has led to a requirement for commitment signals that can be trusted. Zimnisky asks what sends a more reliable signal of sincerity and commitment, a US$800 synthetic diamond ring or a similar-sized US$5 000 natural? De Beers is also looking ahead and asking who the consumers of natural diamonds will actually be. In its 2018 Diamond Insight Report, it notes a number of factors for the future. Firstly, more women are buying diamonds for their own enjoyment. De Beers points out that sales to single women, especially younger females, now account for one-third of US sales.

Secondly, De Beers notes that millennials and the even-younger Gen Z (born after 1996) are ’the most populous generations in the world today’. Millennials, it suggests, will be the highest-spending generation in the diamond market by 2020. The report argues that ‘the desire to be in stable relationships’ among these groups is at least as strong as it was for their parents. Thus there is every reason to think that the link between diamonds and romance will remain intact.

Finally, the new diamond-buying generations are active in ‘social causes, responsible consumerism and sustainability’, which means that the ethical branding of diamonds is going to become ever more important.

The signs are that gem diamonds will remain a long-term investment. As Zimnisky points out, the industry has been resilient. It has overcome ‘anti-trust legislation; threats from cubic zirconia, moissanite and other simulants; the [negative publicity associated with] the blockbuster film Blood Diamond; and generations of changing consumer preferences and cultures’.

It will probably ride out the current synthetics threat with ease. Ultimately it’s up to the values of the human beings who make up the gemstone market, and there is little sign that these have fundamentally shifted.