With the recent buy-in of traditional automotive manufacturers, the rise of electric vehicles (EVs) and other sources of demand for battery-powered devices is creating an unprecedented market for ‘green minerals’ such as cobalt, lithium, graphite and even copper. This offers immense opportunities – and decisive challenges – for a number of African mining jurisdictions, notably the DRC and Zimbabwe.

Increasing demand is shown in the surging prices of cobalt and lithium over the past two years. Cobalt has soared from US$21 700 per ton on the London Metals Exchange in February 2016 to US$95 000 in March this year, a climb of more than 300%. At the same time, the price of lithium has risen from US$6 500/ton in 2015 to US$16 500/ton in 2018.

These two metals are currently non-negotiable components of lithium-ion batteries, used in mobile phones, computers and, in particular, EVs. There are initiatives to develop other battery chemistries, using more common metals, rooted in fears of supply bottlenecks for lithium and especially cobalt, as well as price concerns. However, for the moment, the emerging EV industry is locked into lithium-ion technology.

Until last year, the EV market appeared to be dominated by a single disruptor, Tesla Motors, with its lithium-ion ‘Gigafactory’ north of Reno, Nevada. Headed by South African-born entrepreneur Elon Musk, Tesla Motors has done something unique. In July 2017, it launched the Model 3, the first affordable and competitive EV. According to Bloomberg, Tesla has sold 30 000 vehicles since then and currently manufactures 3 500 per week. The problem is that demand for the product far exceeds the company’s production rate.

Enter the established automotive industry. In 2017, all the major manufacturers announced a massive turn to green technologies. At the Frankfurt Auto Show in September 2017, BMW announced it is gearing up to mass produce electric cars by 2020, and that it will have 12 different models by 2025. Mercedes-Benz is set to launch more than 10 electric vehicles by 2022, and expects to be making as many EVs as traditional petrol and diesel cars by 2025. VW, meanwhile, stated that it will build electric versions of all 300 models in the 12-brand group’s line-up by 2030.

Toyota and Ford/Chrysler have also announced extensive EV programmes, while the Chinese-owned Volvo Car Company said early this year it expected that 50% of its production would be EVs by 2025, partly to conform with the Chinese government’s plan to have ‘new energy’ vehicles account for 20% of the country’s vehicle sales by that date.

According to Kevin Li, China-based senior analyst at Strategy Analytics, ‘sales volumes for new-energy vehicles exceeded 700 000 last year, and this number is further expected to increase to more than 2 million in 2020, and to more than 5 million in 2025’.

Other countries plan to eventually ban petrol and diesel technologies completely. France and the UK want to end sales of vehicles that use traditional fuels by 2040, while the Netherlands has an ambitious target date of 2025.

‘We are in the midst of a significant transition, one that offers a promising investment opportunity,’ says Old Mutual Private Client Securities chief investment officer Andrew Dittberner. He argues that ‘with an increasing list of countries now introducing bans on petroleum and diesel-fuelled cars, the price of cobalt – a key ingredient of lithium-ion batteries used in EVs – has soared’.

Martim Facada, market reporter for the company Industrial Metals, maintains that ‘technology, alongside raw material availability will decide, at the end of the day, which types of vehicle will be most produced’.

The new industry is indeed reshaping the production of the minerals that comprise the main automotive inputs. EVs contain four times the amount of copper as conventional cars, about 80 kg. But it’s the battery metals – cobalt, lithium and graphite – where the supply bottleneck is greatest.

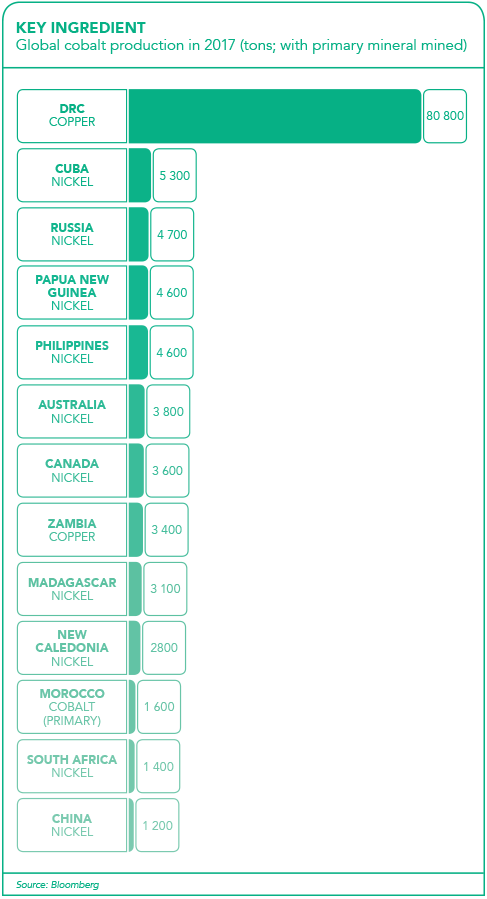

Cobalt is the critical metal, making its point of origin – the DRC being the world’s leading cobalt producer – a subject of considerable competition as well as some concern. Cobalt is almost always a by-product of copper or nickel mining. This means that, traditionally, cobalt production has not been a direct response to market demand but rather an ‘add on’, produced only where the economics of copper or nickel mining already make sense. But price trends over the past two years appear to be changing this. Facada argues that higher prices are seeing an increased appetite for direct investment in cobalt mining.

The big operators in the DRC – Swiss-based Glencore and firms such as Eurasian Natural Resources Corporation, Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt and Congo DongFang International Mining – are currently racing to first increase and then lock down supplies.

There’s uncertainty about the exact figures for cobalt production in the DRC for at least two reasons. Artisanal (informal) miners account for anything up to 20% of the country’s production, much of which exits the country via informal channels. Then there is the fact that most of DRC’s cobalt is exported to China, and some it is shipped in a completely unrefined form with the end recovery rate unknown.

At present, companies are negotiating directly with mines in the DRC to secure future certainty of supply. Players include not only the major automotive manufacturers but also mobile phone giants such as the likes of Apple and Samsung. They are looking to do deals not only with mining companies such as Glencore but also with Chinese battery manufacturers that currently lead the industry.

Lithium supply is a little less constrained than cobalt. Dominated by Chile, with new mining projects planned in Australia, the metal is not subject to the same political uncertainty that bedevils cobalt miners in the DRC. Although most investment in lithium mining is not going into Africa, says Facada, there are promising junior projects in Namibia (Montero Mining), Mali (Kodal Minerals), and potential sites in Zimbabwe.

In Zimbabwe, the most advanced project appears to be Arcadia Lithium, developed by the Australian Securities Exchange-listed Prospect Resources near the country’s capital, Harare. In May, it announced that it expects to secure more than US$55 million in funding for the first phase, and to produce concentrates for export early in 2019.

The lithium projects in Zimbabwe suddenly became a great deal more attractive with the change in government in December last year and the repeal of stringent indigenous ownership requirements soon afterwards. It is significant that one of Arcadia Lithium’s new equity partners is the listed Chinese company Sinomine, which has a seven-year take-off deal with the mine.

A green mineral that receives rather less attention that cobalt or lithium is graphite, which is already mined in many countries. It has traditional applications in the iron and steel industry, where its capacity to withstand heat makes it a viable electrode in furnaces. However, it also has lithium-ion battery applications. Indeed, no less an authority than Elon Musk has suggested that the batteries should more properly be called ‘nickel-graphite’ if percentage composition was the consideration.

Demand for graphite is rising alongside the two main ‘green’ metals. The price hasn’t risen as dramatically but that is partly a result of China, the world’s biggest producer, removing all export taxes on the metal. Several junior miners have been investigating graphite deposits in Tanzania, Namibia, Madagascar and Tanzania. However, the big prizes are in Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado province in the north of the country.

In late 2017, Australian miner Syrah Resources brought a major new graphite mine, Balama, on-stream. The resource on which the mine is based is said to be the largest graphite deposit in the world, being several kilometres in length and more than 200m thick. Two other mines are in develop-ment in the same region (Montepuez and Ancuabe), with both projects also being led by Australian junior mining companies.