As a general rule, when economic times get hard the gold price rises. The yellow metal has, for many decades, been considered a counter-cyclical or ‘safe-haven’ investment; a last store of value when shares, bonds and physical investments are unattractive. A Goldman Sachs research note published in January describes gold as ‘a barometer of fear’. Since the COVID-19 pandemic struck in early 2020 – and global economic activity plummeted – panicked investors climbed into the metal.

When COVID-19 broke, the gold price began an upward surge to levels last seen in 2011 (above US$1 800/oz). As the pandemic continued, it kept rising to an all-time high of US$2 070.50 in August 2020. In the first eight months of 2020, the gold price added more than US$500/oz, an increase of 32%.

As the COVID-19 crisis appeared to ease, following the introduction of vaccines at the end of 2020, the gold price fell back to trade around US$1 800, still well above its pre-pandemic levels. But then came Vladimir Putin’s invasion of the Ukraine. Among the Western sanctions imposed on Russia is a ban on the six London Bullion Market-accredited Russian refineries, which immediately took 330 tons of gold out of the market. At the same time, there was an energy shortage in Europe and levels of inflation last seen 50 years ago in developed countries.

Even before the current round of crises, Goldman Sachs analysts had suggested that a gold price of US$2 350 had become their ‘base case scenario’ for the next year. In their research note in February – before the invasion of Ukraine – Mikhail Sprogis, Sabine Schels and Jeffrey Currie argued that gold’s ‘momentum is only set to accelerate as the market has not yet priced in a US slowdown, which is needed to curb inflation’. To back their argument, they point out that ‘the last time we saw all major [gold price] drivers accelerate simultaneously was in 2010/11, when gold rallied by almost 70%’.

The gold price surged again to near record levels in February and March 2022. While this comes with tough economic news for consumers globally, it is highly positive for gold-mining companies, the countries in which they operate and investors who were already holding the yellow metal. It will spur further exploration and development spending in the sector. But the impact on different regions in Africa varies in ways that have been unfolding for more than a decade.

For the entire 20th century, South Africa was the world’s dominant source of gold, with the biggest and deepest mining operations ever constructed. However, the country’s gold production had been in decline since peaking at around 1 000 tons in 1970. 2006 was the last year in which South Africa was the world’s biggest gold producer, being overtaken the following year by China.

Statistics South Africa, the government’s official statistical service, commented that ‘general historical trends show that gold has lost the prominent place it once had in the South African economy’.

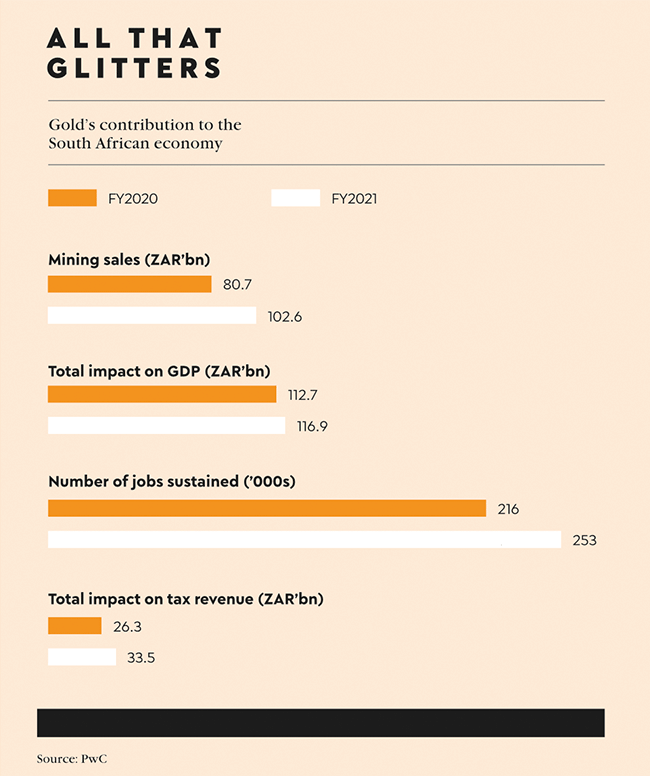

After 2006, South Africa’s slide down the rankings of gold producers was rapid. By 2015, gold accounted for just 12.5% of the country’s total mineral sales, down from the dominant 67% it had made up in 1980. In 2022, South Africa is no longer ranked in the Top 10 globally (it’s 11th) and it’s total production – less than 100 tons (in 2021) – is orders of magnitude behind the world’s biggest three producers (China, Russia and Australia).

A sign of South Africa’s decline is that none of the country’s surviving gold mines is ranked in Africa’s Top 10 by output. The most productive mine on the continent is Kibali, a highly mechanised joint AngloGold Ashanti/Barrick venture in the DRC’s extreme east. In 2020, that mine produced 25 tons of gold. But the major continental trend is shown by the next biggest on the continent. Three are in Ghana, two in Mali and one each in Burkina Faso and Mauritania.

Lebohang Sekhokoane, a mining research analyst at South Africa’s Public Investment Corporation, argues that ‘when you look at the gold sector in West Africa, that’s where the sun is rising’. He adds that ‘the South African sector is mature. Compare that to the new opportunities in West Africa, where operations are shallower, making it easier to mine and there is an investor-friendly environment’. Many gold mines in West Africa do not require deep hard-rock mining. So far, many of the ore bodies discovered are easily accessible from the surface through open-cast methods. Gold Fields, for instance, has three operations in Ghana, all of them open cast (Damang, Tarkwa and Asanko).

The largest of these is Tarkwa, the fourth-biggest gold mine in Africa by output. Gold Fields describes it as a ‘long-life, low-cost surface-mining operation with a robust mineral reserve’.

Ghana is Africa’s biggest gold producer and the only African jurisdiction in the world’s Top 10 (6th) having overtaken South Africa in 2019. International gold mining majors such as AngloGold Ashanti and Gold Fields have shifted their focus from South Africa to West Africa, where deposits are cheaper and easier to mine. They join global gold-mining major Newmont, which already owns two of the largest mines in Ghana: Ahafo and Akyem.

AngloGold Ashanti no longer owns any assets in South Africa, having sold its last major mine, Mponeng (once called Western Deep Levels) to Harmony in a deal completed in October 2020. Gold Fields owns just one mine in the country, the mechanised South Deep operation. This is South Africa’s most recently opened mine and the ore body is expected to last nearly half a century longer than any of the other operating mines.

West Africa, however, is booming. While gold-mine production fell in Ghana and Mali in 2020 thanks to COVID-19 shutdowns, it picked up strongly again in 2021. Overall 12 projects were reported to be in development in 2021 across Ghana, Burkina Faso and Mali. These include Phase 2 of AngloGold Ashanti’s Obuasi mine, where the company has redeveloped what was once an open-cast operation into an underground mine that it describes as a ‘modern, mechanised mining operation’.

This practice – starting with surface mining and moving underground later – may be the face of the future of gold mining in the region. However, there are many social and political challenges, especially in the countries north of Ghana.

Over the past decade, an artisanal gold rush has swept the Sahel from Sudan to Mauritania. Small-scale miners now produce 20 tons to 50 tons of gold in Mali, 10 tons to 30 tons in Burkina Faso and 10 tons to 15 tons in Niger. The sheer vagueness of these totals points to the problem. This is mostly illegal gold, some of which is known to finance jihadist and other rebel activity. The worst affected area is the tri-state region where the borders of Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso join. ‘The violence is more and more concentrated in areas where we know there are also concentrations of gold […]. It’s pretty clear these are related,’ says US Defence Department researcher Daniel Eizenga.

In June last year, a group described as ‘extremists’ arrived on motorcycles at Solhan, an artisanal gold-mining centre in Burkina Faso. They seized the mine and massacred more than 130 people. According to UN reports, most of the assailants were young teenagers. The regional government subsequently banned all artisanal mining in recognition of the link between extremism and gold.

Illegal gold is smuggled out of the tri-state region via Togo and mostly ends up being laundered via the poorly regulated Gold Souk in Dubai.

The relationship between the formal, regulated, tax-paying gold-mining sector and the artisanal sector is fraught across much of the continent. There are literally millions of artisanal gold miners across the continent – 1 million in Tanzania alone, according to estimates by the EU ENACT research project.

For established companies, ‘new’ discoveries become much more difficult in a context of violence, criminality and extremism, which add layers of risk to both exploration and development.