Did you know that Marilyn Monroe’s rendition of Diamonds are a Girl’s Best Friend from the 1953 movie Gentlemen Prefer Blondes was ranked the 12th best film song of the 20th century by the American Film Institute? Its resonance is even more telling when you consider that Celine Dion’s My Heart Will Go On from Titanic (1997) is at 14, and even the King – Elvis Presley – gets his first look in at number 21 with Jailhouse Rock (from the 1957 film of the same name).

Such is the enduring power of the precious stone ‘consisting of a clear and colourless crystalline form of pure carbon’. Not to mention the Blonde Bombshell. Seventy years on from the glamour of the Hollywood screen and diamonds still retain their sparkle as the symbol of enduring beauty, wealth and everlasting love.

However … times change. In January this year, only days apart, several bits of news shook up the international diamond industry. Most dramatically was the news that De Beers – the company established in 1888 and which has for generations dominated the global diamond market, and is the world’s largest rough diamond producer by volume – was cutting prices by about 10% across the board at its first sale of the year. Bloomberg, quoting un-named sources, said larger cuts – about 25% in one category – were made for bigger gems.

‘The industry has been whipsawed since the start of the pandemic,’ reported Bloomberg. ‘It was one of the great winners as stuck-at-home shoppers turned to diamond jewellery and other luxury purchases. But demand quickly faded as economies reopened, leaving many in the trade holding excess stock that they’d paid too much for.

‘The cooldown rapidly escalated as the crucial US market wobbled under rising inflation. In addition, consumer confidence in key growth market China was hurt by a property crisis, while competition from lab-grown diamonds increased. That left the industry with little choice but to curb supply. Russia’s Alrosa in September halted all sales for two months, and was followed by buyers in India – the dominant cutting and trading centre – voluntarily banning imports.’

De Beers holds 10 sales each year for its ‘sightholders’, as buyers are termed, and in January’s, usually the most important, the biggest price reduction was in the ‘select makeables’ category. These are gems between 2 carats and 4 carats, high-quality but not flawless, that can be cut into smaller stones and polished for use in wedding or engagement rings.

‘Even after cutting prices for that category heavily last year, De Beers lowered them by another 25% this month,’ Bloomberg reported. ‘Those gem types have been badly hit by the growing popularity of synthetic diamonds – which themselves have slumped in price.’

Analysts posed the question whether the latest cuts would build some momentum in the market. ‘Prices started to rebound toward the end of last year as buyers who were short of stones and needed new stock to keep factories open fuelled demand amid limited supplies,’ said Bloomberg.

Only a few days before that news broke, De Beers announced that the board of Debswana, the joint venture between itself and the government of Botswana, had approved a huge investment into the Jwaneng mine in the country.

According to De Beers, the US$1 billion investment will pave the way ‘for the world’s most valuable diamond mine’ to transition to underground operations from its current open pit workings.

‘This phase of works, known as the “exploration access development phase”, is for establishing a drilling platform to facilitate comprehensive sampling of the kimberlite pipes, delivering the early access decline for the underground mine and developing essential infrastructure to support forthcoming stages of the project,’ De Beers said. ‘The initial works, to start in May 2024, follow the successful completion of feasibility studies. Following the exploration access development stage, the project will be developed in two further phases, Phase 1 mining and Phase 2 mining, to support long-term future production at the mine in an environment of tightening long-term diamond supply.’

Al Cook, the CEO of De Beers and deputy chairman of Debswana, was quoted as saying that ‘Jwaneng stands proudly as the world’s greatest diamond mine. It is a central pillar of both the Botswana economy and the De Beers Group business. The global supply of natural diamonds is falling, so moving forward with the Jwaneng underground project creates new value for investors, brings new technology to the country, creates new skills for our workforce and provides new gems for customers around the world. This investment is aligned with our strategy to prioritise investments in the highest-quality projects’.

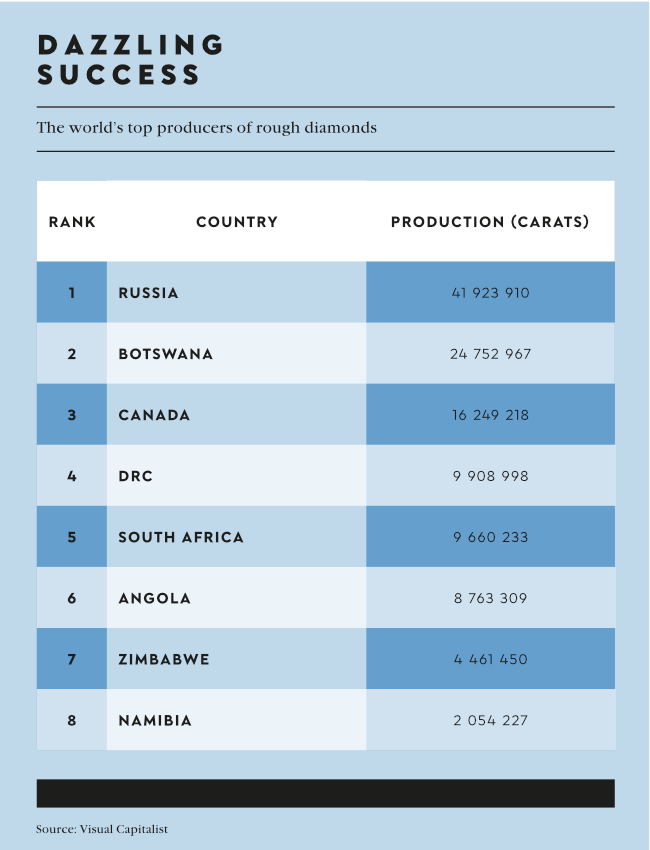

According to De Beers, Jwaneng has ‘produced an annual average of almost 11 million carats per year’ since its establishment in 1982. Although Jwaneng has dominated African diamond mining for 40 years it could have some competition soon. In late November last year, the Angolan government said mining had officially begun at the country’s Luele project, one of the world’s largest diamond mines by reserves.

Luele contains an estimated 628 million carats of diamonds with a lifetime of 60 years, according to Reuters. ‘This is the only major new diamond mine in the world that will commence production this decade,’ the news agency quoted independent diamond analyst Paul Zimnisky as saying. ‘It’s fair to say Angola is the most prospective nation for diamonds.’

The US$600 million project has an initial processing capacity of 4 million tons of ore a year with a gradual ramping up over several years to 12 million tons. According to Reuters, Luele has apparently already mined 5 million carats of diamonds in its pilot phase of production.

It remains to be seen what a more longer-term influence Luele will have on the industry. The country is home to the Catoca mine, currently its biggest, and the fourth-largest globally. In addition, Australian company Lucapa recently found a 235-carat stone from the Lulo mine, near Lunda Norte, 630 km east of the capital Luanda, only a week after a 208-carat diamond was uncovered at the same location.

Lucapa holds 40% of Lulo, which has so far revealed 40 diamonds weighing more than 100 carats (with four over 200 carats included the 404 carats ‘4th February Stone’, the largest ever found in Angola).

‘Lulo continues to demonstrate it is a prolific producer of large diamonds. To unearth three +100-carat diamonds – with two being over 200 carats – in such a short space of time from different areas of the concession, makes us more determined to find the primary source, by dedicating even more resources to the exploration programme,’ said Lucapa’s MD Nick Selby.

Angola has been stockpiling more than a 1 million carats in anticipation that prices will rise.

In recent years ethical and sustainable practices in the diamond industry have gained much more prominence, addressing concerns related to the environmental and social impact of diamond mining.

For example, in November last year De Beers hosted the Natural Diamond Summit, in partnership with Botswana’s Ministry of Minerals and Energy, in Gaborone. It explored the theme ‘Sustainability: People, Product and Planet’.

In his opening address Botswana’s Minister of Minerals and Energy, Lefoko Maxwell Moagi, said: ‘The natural diamond industry has been in existence for over 100 years. Throughout its history, the industry has experienced many changes. From major technological advances that have transformed productivity and supported value-chain development to consolidation of industry players and diamond centres, the sector has seen major evolution, and has continued to grow and expand to become a leading driver of development throughout the producer countries and across the value chains. The industry has thrived for decades, transcending many global challenges that have seen other industries and major corporations fail to survive.

‘Our diamonds are not just gems; they are the foundation upon which the hope and promise of our economies has been built. They are the engine through which our aspirations for greater wealth, more diversified economies, the development of people and a more fair and equitable future can be realised. But this potential can only be fully harnessed if we embrace a new paradigm, one that places sustainability at its very core.’

The industry will survive this rough patch. In the contemporary era, where trends and preferences often evolve rapidly, diamonds will continue to hold their allure as coveted symbols of luxury, beauty and the perception of exclusivity. This lies not just in their intrinsic physical properties but in the narrative woven around their scarcity. That rarity that no two are ever exactly alike no matter how beautiful they are. Just like movie stars such as Marilyn Monroe and Judy Garland, who sang Over the Rainbow from the Wizard of Oz (1939). That was judged the number one film song of the previous century, by the way.