The US five-cent coin, universally known as a nickel, has been in production since 1866. Actually, the five-cent coin was first introduced in the US in 1794 but then it was made of silver and known as a ‘half disme’ (pronounced dime in the US).

Technically, the nickel isn’t made completely of, well, nickel. It’s cupronickel, an alloy of copper with some nickel (about 25%) and other elements such as iron and manganese added for strength. Strangely, despite its high copper content (between 60% and 90%, according to the US Mint) cupronickel is silver in colour.

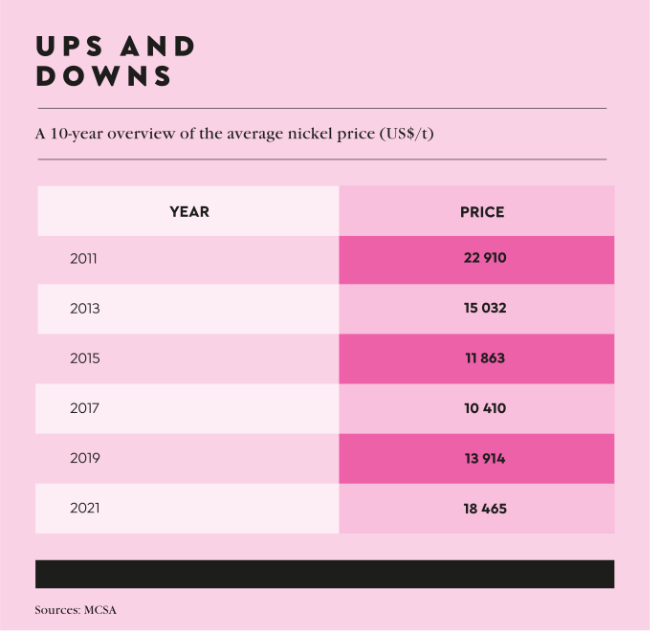

These days, five cents won’t buy you a lot – the commodity nickel is another story though.

In March last year, the London Metal Exchange (LME), the world’s oldest (established 1877) and most important metals commodity exchange found this out the hard way.

After the Russian invasion of Ukraine, in the space of a couple of days, the price of nickel per ton on the LME went from US$25 000 to around US$55 000, then yoyo-ed to US$35 000. Short sellers then sent the price on March 8 through the roof on some trades to more than US$100 000. The LME was forced to temporarily stop nickel trading and cancel some of the March 8 trades (it is now being sued for nearly half a billion dollars over this). Circuit breakers were put in place on nickel trading.

The fiasco disrupted nickel trading to such an extent that Reuters reported in early April 2022 that ‘the average daily volume of combined LME nickel futures and options slumped to 64 952 lots in March compared to 90 685 a month earlier and 88 342 in January’.

Nickel is the fifth-most common element on the planet and is highly prized for its ability to be used in alloys, and its strength, rust resistance and heat tolerance. Until recently most nickel was used in the making of stainless steel, usually in China, but the surge in battery technology, especially for electric vehicles (EVs), has seen it become one of the so-called ‘green minerals’ and hence subject to much speculation.

‘It has been an extraordinarily volatile year for the nickel market, including some big price swings that were not tied to traditional supply-demand dynamics but rather the uncertainty of what impact such factors as the war in Ukraine and Chinese COVID-related lockdowns will have on the global economy – and therefore demand for nickel and other base metals,’ analyst Myra Pinkham noted in a research paper in the middle of last year for Fastmarkets.

‘There are also questions about whether in the medium to long term there will be enough nickel supply – particularly Class 1 nickel – to meet an expected growth in demand for nickel-containing electric vehicle batteries.’ Fastmarkets said that Russia is responsible for about 6% of the world’s supply, and the country accounts for around 17% of the world’s Class 1 nickel (or nickel sulphate), which is used in EV batteries.

Quoting experts, Pinkham said that ‘nickel prices were already high before the Ukraine invasion’, and ‘by 2040 its usage could climb to as high as 2.2 million tons’.

The Fastmarkets report noted that ‘primary nickel usage in EV batteries will increase by about 25% in 2022’. It mentions that despite EVs currently having a 5% to 8% market share of the world’s light vehicles, ‘by 2035–50 they could make up about 50% of the market’. Given this sort of growth, there would be a need ‘to increase Class 1 nickel supply by about 1 million tons per year by 2030’.

In September, Vale, the Brazilian mining company with global operations, said it expected worldwide demand for nickel to increase 44% by 2030 ‘compared to that expected for this year, due to high demand for use in batteries that power electric vehicles’. In a statement released to Reuters, it said that ‘demand for nickel is forecast to increase rapidly this decade with the energy transition’. It added that its own production of the mineral would increase between 230 000 and 245 000 tons per year ‘in the medium term’ compared to 190 000 tons currently.

In South Africa, according to a Department of Mineral Resource and Energy report, nickel occurs mainly in a 250 km-long swathe across the North West and Limpopo provinces, as part of the Bushveld complex, where ‘it is extracted as a by-product in platinum group metals [PGMs] mining’.

The five biggest South African nickel mines by production in 2021, according to Mining Technology, were Anglo American’s Mogalakwena in Limpopo with an estimated output of 15 449 tons; Nkomati in Mpumalanga owned by African Rainbow Minerals (ARM) and Norilsk Nickel Africa (8 016 tons); Union in Limpopo owned by Siyanda Resources (4 600 tons); Impala in North West owned by Implats (3 945 tons); and Sibanye-Stillwater’s Thembelani, also in North West (3 858 tons).

Only Nkomati is a dedicated nickel mine. Actually, ‘was’ … since its underground operation was placed on a care and maintenance programme in December 2015, and in March 2021 the partners announced that, owing to low nickel prices, it was placing the open-pit mine on care and maintenance too. According to Mining Weekly, ‘total mineral resources as at June 30, 2019, were estimated at 46.35 million tons grading 0.40% nickel, 0.13% copper, 0.02% cobalt and 0.97g/t platinum, palladium, rhodium and gold’. Cue March 2022 … when ARM CEO Mike Schmidt said the partners were considering re-opening the mine.

‘We’ve always said we put the mine on care and maintenance and will wait for better prices,’ Schmidt told Mining Weekly. ‘The question raised is “you’ve got the good prices; what now?” So, we are busy with study options with our partner and we are considering a number of options in terms of the way forward,’ he said. Yet by September last year, Reuters quoted Schmidt as saying ARM was not convinced the nickel price was sustainable and the company was still undecided on restarting operations. ‘The nickel price today is elevated, but if you look at the long-term outlook or consensus, it’s not there yet,’ said Schmidt. He added they would carry on assessing the situation.

It would seem that the nickel rollercoaster continues its ride.