Palladium has recently been a speculator’s dream. The metal hit its highest ever price in March 2019, surging to US$1 620 an ounce. The metal, part of the platinum group metals (PGMs) basket, is trading at a premium to platinum (in excess of US$500) last seen briefly in January 2001. This has profound implications for the world’s PGM miners, with companies asking how long the situation is likely to last and what it implies for future mine developments.

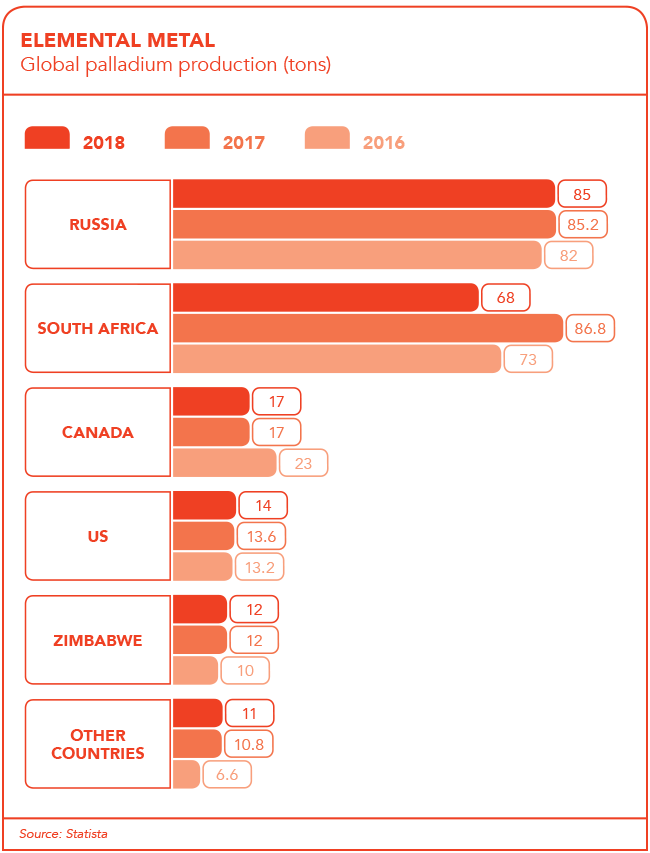

Palladium and platinum mostly come out of the same mines. But the proportional mix of the two minerals varies enormously. The biggest palladium producer in the world, Russia’s Norilsk Nickel (Nornickel), produces four times more palladium than platinum. The company produces 41% of world supply from its Arctic-based network of operations.

Yet Nornickel illustrates one of the features of palladium mining. The metal has been little more than a by-product of its other mining operations. Nornickel’s main businesses are nickel and copper mining. It is the world’s largest nickel miner and is also ranked among the world’s top 10 copper producers.

The relatively marginal position of palladium has traditionally been the case with all PGM producers apart from two palladium specialists in North America (Stillwater and North American Palladium).

Even though Nornickel made a handsome profit from its palladium operations in 2018, with palladium accounting for 28% of total sales (US$2.35 billion), the company seems to essentially regard this as a windfall. It has no immediate plans to invest in more production and boost volumes of the white metal. Most of its recent US$2 billion capex has gone into a copper project (Bystrinksy).

There have been hopes that palladium’s bull run will bail out South Africa’s hard-pressed PGM miners. The country possesses 80% of the world’s reserves of PGMs. But in 2018, Bloomberg reported that more than half of South Africa’s PGM output was estimated to be unprofitable. Earlier this year, in response to electricity price increases, Minerals Council South Africa (MCSA) chief economist Henk Langenhoven suggested there was a danger of this figure rising to around 75%.

MCSA CEO Roger Baxter comments that ‘the sector is in crisis. Over the past five years, it has struggled with an oversupplied market, a function of structural changes in global supply and demand fundamentals, including increased growth in recycling, flat new-mine supply and weaker demand, domestic labour strife, declining productivity and rapidly escalating costs’.

There is no doubt that the surging palladium price has helped the South African industry. The impact differs among the four major producers (Anglo American Platinum, Impala, Sibanye-Stillwater and Northam) though.

The biggest beneficiary has probably been Sibanye-Stillwater, which finally took possession of the world’s fifth-biggest PGM miner, Lonmin, in June this year. Sibanye-Stillwater – originally an operation consisting of four marginal gold mines spun out of Goldfields in 2012 – has alarmed analysts as it racked up debt while pursuing acquisitions at every turn.

The company acquired, in quick succession, Aquarius Platinum and Anglo Platinum’s Rustenburg mines (both announced in September 2015), then Stillwater (December 2016) and, finally, Lonmin. At that point, the company’s debt was 2.6 times underlying earnings and the markets were starting to protest. ‘There is too much debt. We are seeing a lot of balance sheet risk building up,’ says Arnold van Graan of Nedcor Securities.

Yet the Stillwater transaction has changed the picture. The mine in Montana is a pure palladium producer and the acquisition boosted Sibanye’s ratio of palladium to platinum to 50/50, the most palladium-heavy of all miners after Nornickel. The company has also resorted to other strategies to buy down its debt. Selling gold production forward to Wheaton Precious Metals brought a cash injection of US$500 million.

However, none of the South African miners appears to be relying solely on palladium to improve their prospects. For Sibanye-Stillwater, the acquisition of Lonmin actually lowers the proportion of palladium in its mix, as the Lonmin assets are located on the western limb of the Bushveld complex, which is less palladium-rich than the northern limb.

Anglo American Platinum (Amplats) has also done especially well out of the palladium surge. The company’s only remaining major asset in South Africa is also the world’s biggest open-pit mine, Mogalakwena, which is highly geared towards palladium. Amplats was able to forecast spectacular half-year results in June with headline earnings expected to be 80% higher than they were a year ago.

The impact of the palladium price rise on Impala Platinum (Implats) and Northam Platinum has been less spectacular but still positive. ‘It’s a tremendous difference from a year ago but we are not out of the woods yet as a sector,’ said Northam CEO Paul Dunne in May. He added that the PGM basket price would need to rise another 20% for most South African mines to be sustainable.

Implats is particularly troubled. Last year the company said it was losing ZAR2 billion a year and the only way ahead was job cuts, which could affect up to 13 000 employees as the company seeks to eliminate loss-making areas of production.

While conditions remain tight, Implats has returned to profitability on the back of the improved PGM basket price in 2019. ‘We have customers asking to buy all our palladium and rhodium. [But] that demand does not fully compensate for losses from mines that produce mainly platinum,’ says Implats group executive: corporate affairs Johan Theron. Implats is reported to be considering raising its stake in a palladium deposit owned by Platinum Group Metals, which operates in the Bushveld complex.

Implats’ retrenchment plans are paralleled by a similar strategy at the former Lonmin assets now owned by Sibanye-Stillwater. These plans have aroused the ire of South Africa’s Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (Amcu).

Ahead of the annual mid-year wage negotiations, Amcu has tabled a minimum wage demand of ZAR17 000, a massive jump from the ZAR12 500 of previous rounds. The higher palladium and rhodium prices are clearly a factor in this. ‘We are really glad that it is going so well with platinum and it is high time that the bosses share their hyper-profits with the workers who toil every day,’ says Amcu boss Joseph Mathunjwa. Amcu is associated with long strikes.

The union has only recently emerged from a five-month stand-off with Sibanye-Stillwater’s gold mining division, during which there were nine deaths. The problem is that Amcu faces the threat of deregistration if the union does not hold a leadership conference (scheduled for September) and Mathunjwa wants a success to take into that event.

While all South African platinum miners face the threat, those with the most labour-intensive operations (Implats and Sibanye-Stillwater) are more vulnerable to disruption.

The prospects for both palladium and its close relative, platinum, are intimately related to trends in the automotive industry. The biggest use of both palladium and platinum is in automotive catalysts. Although palladium is more widely used in petrol-engined vehicles and platinum in diesel engines, the two are to some degree interchangeable.

Some regard the rise in demand for palladium as a result of its relative cheapness prior to 2016. But there was a technical component to the shift in relative demand from platinum to palladium. Over the lifespan of an autocatalyst, palladium is less effective at removing sulphur from emissions.

However, increasingly stringent regulations in the US and EU have seen an improvement in the quality of petrol (less sulphur), making palladium a more viable substitute for platinum. In addition, consumer reactions to Volkswagen’s 2015 ‘Dieselgate’ scandal (where the company had intentionally programmed engines to produce lower emissions readings during tests) have seen the market for diesel-engined vehicles contract in Europe and North America.

According to PGM market-watcher Johnson Matthey, ‘world output of light-duty diesel vehicles contracted by around 4% in 2018, due to a 10% drop in European production’. In fact, production volumes for diesel cars in Europe fell by nearly a million units in 2018. Johnson Matthey’s May 2019 report indicates that platinum availability is marginally lower than demand in mid-2019 – supply is 6 189 thousand ounces (koz) while demand is 6 316 koz. With palladium, demand also exceeds supply (7 805 koz versus 6 996 koz).

The situation will not last forever. A 2019 Reuters poll found that, in the opinion of 27 analysts and traders, palladium will cost an average US$485 an ounce more than platinum this year, a record-breaking premium. Those polled, however, believe the gap will narrow in 2020 as the rally fizzles out and platinum recovers after an eight-year downturn. But they are not bullish about platinum in the immediate future.

The median forecast for platinum was US$865 for this year, the lowest annual average since 2004, rising to US$925 in 2020. Mining companies have reacted rationally to the palladium price surge. They have gratefully accepted the windfall while not doing much to indicate that they are counting on it in the longer term.

For South African miners it is a temporary positive element in a much bigger equation. But it does provide some relief from the prevailing headwinds, especially labour and electricity prices.