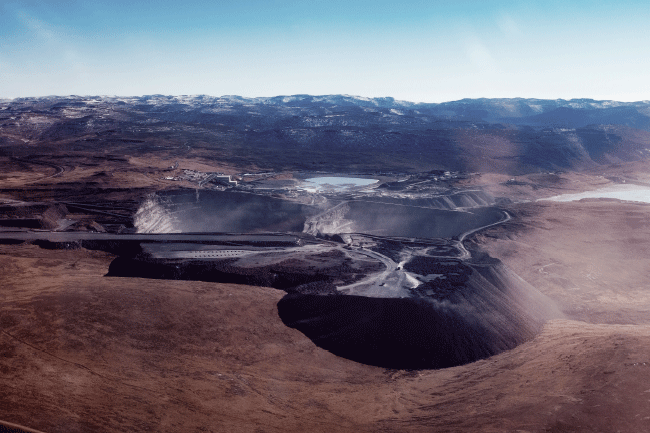

North-eastern Lesotho is gemstone country. Some of the biggest and best diamonds mined in recent years have come from a series of kimberlite intrusions found in an area with a radius of not much more than 50 km. While there have been sporadic attempts to mine diamonds in the region – most notably by Rio Tinto (1969–1972) and diamond giant De Beers (1977–1982) – none were sustainable until Gem Diamonds reopened the Letšeng mine in 2006. Today there are four main companies active in the area, two of which started mining since 2016.

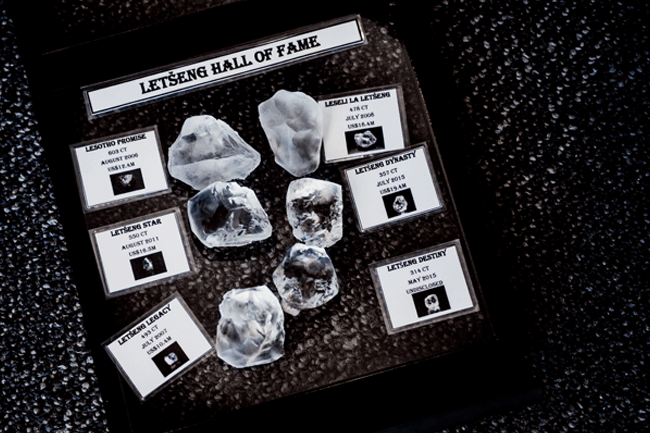

In early 2016, the fifth-largest diamond ever found, a 910 ct monster, was unearthed at Letšeng. It was sold in March 2018 for US$40 million. The Letšeng mine, jointly owned by Gem and the government of Lesotho, has subsequently set a world record for the number of diamonds larger than 100 ct found in a year. It recovered 15 such stones in 2018.

The diamond potential of Lesotho, then a British protectorate called Basotholand, was first identified in 1947, but until 1969 all activity was conducted by informal artisanal miners. As so often in Africa, these were the true pioneers, without whom the viability of the resource may never have been established. The Eureka moment came in 1967 when a local digger, Ernestine Ramaboa, found a 601 ct brown diamond in the Letšeng area.

Ramaboa and her husband Petrus concealed their discovery and walked for four days across the mountains to the capital, Maseru, where the government stepped in to ensure their safety. The stone, which came to be called the Lesotho Brown, netted the Ramaboas US$300 000.

It was cut into 18 stones, of which one, a 40.42 ct marquise, was purchased by Aristotle Onassis and given to Jacqueline Kennedy for her engagement ring. It was sold in 1996, as part of the former US First Lady’s estate, for US$2.6 million.

The primary characteristic of Lesotho’s diamond fields is the low grade of its diamondiferous kimberlite, typically less than 2 ct per 100 tons mined. But the quality of stones is extremely high, which means the industry pays an exceptional price per carat. In 2014, the carat value of diamonds from Letšeng was 21 times the global average. That mine is the world’s most consistent source of type IIa diamonds – gemstones with exceptionally low nitrogen content, which tends to make them more ‘makeable’ (easier to cut into a single large diamond). What makes the low grades of Lesotho viable is that among the gems produced are very rare large diamonds.

Letšeng mine has produced six of the world’s 20 largest diamonds. But this characteristic is a double-edged sword for diamond miners. Their business models depend on these large discoveries. Without them, operations are not financially viable. Indeed, there is a long track record of financial difficulties for companies operating on the Lesotho diamond fields.

Of the four significant mining companies in Lesotho, one (Namakwa, which operates the Kao mine) had to delist in 2013 after being unable to service its US$360 million debt. It still mines, now under the ownership of a Ukrainian equity fund.

Firestone is the biggest producer in carat volumes on the Lesotho diamond fields. According to the company, ‘care and maintenance activities continued during the quarter [ended 30 September 2020] to preserve cash and to retain our ability to recommence operations when the market for Liqhobong production has recovered sufficiently’. Firestone, which has operated the US$185 million Liqhobong mine since late 2016, added that it was in talks to confirm a debt standstill arrangement with Absa until September 2021.

The other two miners are Lucapa Diamond Company (which owns the Mothae mine and commenced commercial production at the beginning of 2018) and Gem Diamonds. The latter recovered a 603 ct stone (the Lesotho Promise), which was sold for US$12.4 million in 2006. This was the find that, in the words of an industry insider, ‘gave us the confidence to go ahead and invest in the [Lesotho] industry’.

Gem Diamonds produces very small volumes – only 113 974 ct in 2019 – but among these are impressive big gemstones. In 2019, 37% of Gem Diamonds’ total revenue came from just 27 stones. Yet discoveries of 100 ct-plus stones fell in 2019 compared to the previous year (to 11, down from 15), and the decline showed in the company’s bottom line. Profit fell from US$52.4 million in 2018 to US$15 million in 2019. Combined with general downward pressure on the diamond market, this news saw the company’s share price fall to an all-time low.

Diamond mining is a massive boon for the mountainous, land-locked kingdom of just less than 2 million people. Lesotho is surrounded by South Africa and highly dependent on its linkages into its giant neighbour’s economy.

Until this century, its main export was labour to the gold mines of South Africa. By some estimates, in the late-1970s, half of Lesotho’s able-bodied male labour force was employed on the gold mines and the government received half its revenue from migrant remittances.

Employment on the gold mines of South Africa peaked at 127 000 in 1990. But even at that point it was clear that the numbers were not sustainable as South African mining houses responded to political change by settling workers around the mines and converting single-sex hostels for migrant labour into family units. By 2019, the number of Lesotho-resident miners in the South African industry had fallen to 45 000.

Until recently, Lesotho might have been mistaken for any ‘labour-sending area’ in Southern Africa. It retains many of the underdeveloped, deep-rural characteristics of the areas that have traditionally sent men to the gold mines. Eighty percent of Lesotho’s population is dependent on subsistence agriculture (according to the AfDB). However, there have been attempts to free the economy from its dependency on sending migrant labour, and the emerging diamond industry can be seen as part of this trend.

Lesotho has very few natural resources. Apart from the western lowlands, it consists of one mountain chain after the other, and commercial agricultural potential is minimal. Aside from diamonds, there are no minerals beyond traces of uranium and building industry inputs (sand, clay and gravel).

From the Lesotho government’s perspective, the biggest problem is accessing independent sources of revenue. In 2000, more than half of government revenue came from Lesotho’s share of Southern African Customs Union (SACU) receipts. SACU maintains a system of free trade among its five members (South Africa, Botswana, Namibia, Lesotho and Eswatini) and it charges non-members a common external tariff.

With ongoing moves to free up trade for the entire African continent, however, Lesotho’s share of SACU receipts has dropped dramatically over the past two decades and was estimated, by the World Bank, to be a mere 15.2% for 2019/20. In 2016, the government of Lesotho announced its ambition to increase diamond production from 300 000 ct per year to 1.5 million ct. Thanks mostly to Firestone’s high-volume operation (approximately 750 000 ct to 850 000 ct/year), the country’s production volumes reached 1.3 million ct in 2018.

Although the government of Lesotho owns part of all the significant companies operating in the country’s diamond fields, there are some murky areas in its financial relationships with the industry. It is possible, however, that diamond revenue contributes up to 5% of Lesotho’s GDP. Unfortunately, the diamond market was depressed even before the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic roiled the world economy. The Lesotho industry is heavily dependent on discoveries of big, high-quality gems, but the price of such stones has historically been much more volatile than that of lower-grade diamonds. Most diamond miners went into lockdown as the pandemic ran its course. Their futures depend on how buoyant demand for their premier product will be when the global economy stabilises.

By David Christianson

Images Gallo/Getty Images