Since April last year, mining firms in South Africa – and the country’s broader public – have been waiting for the implementation of the redrafted Mining Charter. The modified charter was due to be gazetted at the end of March (a deadline not met). In May the country’s mining minister referred to it as ‘a revolutionary tool’. It already faces opposition from the Chamber of Mines and other industry bodies.

Investors and mining houses are watching closely to see how various proposed revisions, first announced last year, will be written into law. The new draft comes at a time when the country faces systemic economic instability and concerns about credit ratings, and the requirements of the redrafted charter could significantly exacerbate or diminish these concerns.

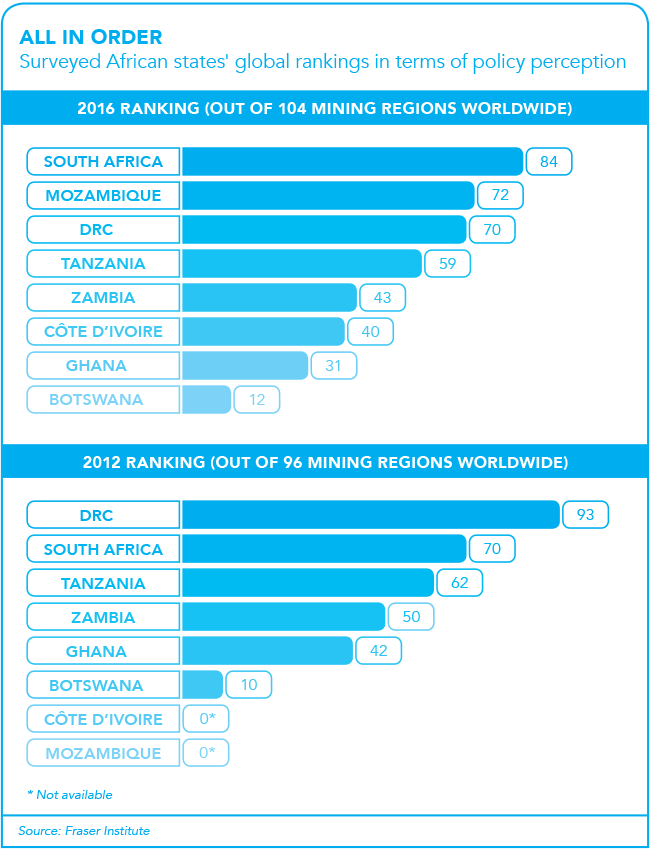

According to a 2001/02 Fraser Institute mining survey, South Africa was rated 13th globally in terms of investment attractiveness – and first in Africa – out of 47 international mining jurisdictions surveyed. The think tank has conducted surveys of mining regions since 1997, sending questionnaires to junior and major mining companies about their operational and exploration outlook – the companies surveyed represent a major share of global mining exploration expenditure in any given year. In 2001, South Africa was ranked 28th in terms of ‘policy potential’, which indicates perceptions of state minerals licensing.

By 2006, South Africa was rated 53rd for mineral policy potential out of 65 countries and regions surveyed by the Fraser Institute, and was ranked seventh of the nine African countries included in the report. In terms of investment potential – measured as the perceived mining potential of a region given its current legal framework – South Africa had fallen from 14th to 55th place out of the 65 countries surveyed.

This decline has continued. In 2016, the country was ranked 74th of 104 regions surveyed for mining investment attractiveness, and 13th of the nearly 20 African states in the survey. It was ranked 84th of 104 regions for its policy potential – only South Sudan and Zimbabwe were lower among African states.

The tail-off in mining sector enthusiasm has serious implications for a country like South Africa, which has been estimated to hold the largest metal and ore reserves of any country globally – valued at around US$3.3 trillion in 2014. Like many African states, its economy depends on the best use of its mineral endowment. For this to happen the minerals licensing system has to be clear, efficient and a dependable base for future investment.

‘Licensing’ covers a very broad range of mining activity – from the granting of a mineral right and mining licence, to the subsidiary environmental or operational permitting that governs day-to-day operations and leads towards eventual mine closure.

In some areas, South Africa’s minerals licensing regime is relatively permissive. Unlike in Canada or Australia, for example, mining companies in South Africa can begin development of a licensed mining lease before final compensation has been agreed with the surface owner of the land. In other areas, licensing in South Africa is markedly more complex, including in terms of the ownership requirements that need to be met for a mining right to be maintained. This area is a key focus of attention for the redrafted Mining Charter.

Analysts at BMI Research argue that uncertainty regarding implementation of the contested ownership requirement, which stipulates that a mining company maintain a consistent 26% level of black participation, will continue to weigh on the South African mining sector after the charter’s precise details are gazetted. The analysts say that ‘even as a rise in iron ore and gold prices have improved the outlook for major miners in the country, policy uncertainty regarding the final conditions of the charter and a generally declining investment environment in the country will mean any recovery is short-lived’.

Criticisms have also been made of South Africa’s ‘first in, first assessed’ system for granting a mining right. This system was intended to ensure fairness – it grants first consideration to the earliest application for a particular mining right. However, a recent report from the Institute of Race Relations argues that the system is vulnerable to abuse, noting the case of Kumba Iron Ore and the Sishen mine. Here, a relatively unknown company was able to gain access to a large stake in the Sishen mine, although its licensing application appeared to have been submitted after Kumba Iron Ore’s own application – the Constitutional Court eventually found in Kumba’s favour.

Various other licensing concerns have also affected South African mining, according to Rita Spalding and Jonathan Veeran, partners and mining law experts at legal firm Webber Wentzel. ‘In our experience, the biggest difficulty companies face is inefficient administration,’ says Spalding.

‘A company will apply for a mining right, and although there’s a time period stipulated in the legislation, these periods are simply not adhered to by any stretch of the imagination. This has huge implications for the mining company – you just never know when your licences are going to come through, and similarly with renewals.’

Spalding adds that there are also problems with competing claims that arise from the cadastral system and the areas granted under mining or prospecting rights.

‘There’s an internal appeal process for resolving competing applications,’ says Veeran. ‘But it’s enormously inefficient – it takes years to go through that process. And even then, it’s usually only when you actually go to court that the matter is resolved. And a lot of that can be politically driven. For example, if you do not have the right empowerment partners, you may not get dealt with as quickly as others.’

Veeran points to the recent case of Aquila Resources, handled by Webber Wentzel, as an example of the difficulties that companies can face, and as an important case for future claim resolution. Here the High Court recently found against the Department for Mineral Resources (DMR), which had improperly sought to set aside the company’s mining rights in the Northern Cape.

The court not only restored Aquila’s mining rights but also found that the DMR had displayed systemic incompetence. Meanwhile other companies involved in the dispute were found to have deliberately obstructed Aquila’s exercise of its right.

Turning to Africa more broadly, some potentially positive legal developments have taken place. Writing in Business Day, mining law expert Peter Leon noted the benefits that may follow from the African Mining Vision Private Sector Compact, announced at the African Mining Indaba in 2016 and reaffirmed this year. Intended to create closer collaboration between mining companies and governments, the compact aims to develop mutually determined standards in various areas, including the refinement of minerals licensing policies across African states.

Licensing regimes across the continent vary enormously, and a particular country’s licensing requirements can have a decisive effect on how it is perceived by mining companies and investors. In the 2016/17 Fraser Institute survey, Botswana was the top-ranking African state for its mineral policies, and the 12th most attractive mining jurisdiction worldwide in terms of policy. As a state that depends largely on forex earnings from mining, its licensing policies are closely tailored to companies’ needs. Licensing in Botswana is often hailed as fast and dependable – a licence will be granted if a relatively straightforward list of requirements is met.

At the other end of the scale are countries where open conflict or policy instability mean companies cannot count on the success of any licensing application. The latest Fraser survey lists Zimbabwe, Afghanistan and Venezuela as the least attractive mining regions in terms of mineral policy.

By giving the perspective of mining-related companies only, the Fraser survey doesn’t necessarily indicate whether a particular jurisdiction’s licensing policy is effective in the pursuit of broader national economic goals – or if a state’s overall policy environment is conducive to sustainable business practice. In 2016, for example, mining companies ranked Eritrea’s policy attractiveness ahead of regions such as France and the state of California.

The survey nevertheless acts as a critical barometer for the mood of the global mining industry towards a state’s minerals licensing and other policies. In South Africa, industry bodies are already launching court cases in response to the uncertainty and shifting requirements of the new Mining Charter, and potential investors are waiting to see how workable the redrafted licensing laws will be. If they cannot be convinced, the effects will be more far-reaching than a low score from the Fraser Institute.