Currently, at least three lawsuits are under way in South African and UK courts, as law firms bring cases on behalf of miners who suffer from silicosis, a debilitating disease caused by a lifetime’s exposure to mineral dusts – notably from the crushed quartz associated with gold production.

The scale of this problem has been well documented since the end of apartheid when it was effectively hidden from view. Observers worldwide are watching the current cases to see what implications they will have – both for the affected workers and for the prosperity of the mining sector.

While these cases have centred around South African mines, they hold possible implications for other African states with an established mining industry. Current and former miners are increasingly aware of the historic risks they have faced, and there is increasing potential for similar legal action in other parts of the continent.

South Africa is one of several African states with a long history of gold mining. Another notable example is Ghana, where gold has been exported since the 17th century. Gold mining in the country was greatly expanded under British colonial rule, leading to a stark rise in cases of silicosis and tuberculosis (TB) among migrant miners from Ghana’s north.

A similar process took place in South Africa from the mid-19th century. As the Witwaters-rand goldfields were developed, the incidence of silicosis increased dramatically, drawing international medical attention. South Africa hosted the world’s first silicosis-related conference in 1930, and led the world in researching the effects of another miners’ disease – asbestosis – in the 1950s. But, given the country’s race relations over the last century, efforts to mitigate these diseases were often directed at the minority of white mineworkers.

The incidence of silicosis among present and former miners has increased since the end of apartheid. A study last year by Gill Nelson, at the University of the Witwatersrand, calculated that around 32% of black mineworkers showed signs of silicosis at autopsy in 2007, up from a reported 3% in 1975. This is perhaps a sign of the greater extent to which the disease is currently monitored, rather than of very low levels in the 1970s. Awareness of silicosis has increased as the scale of the problem has become clear over the past 20 years, and as current lawsuits have progressed.

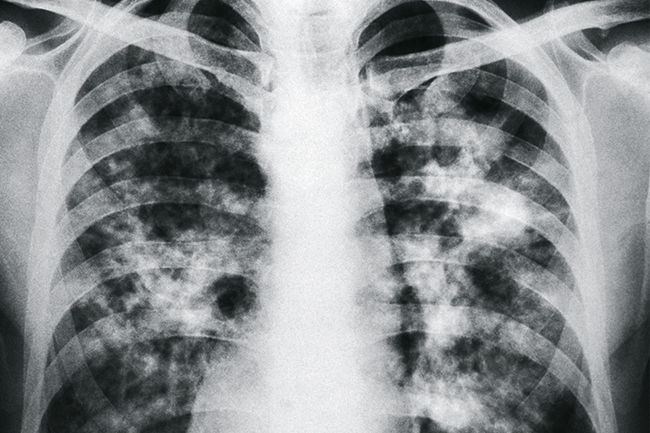

Research into the disease has also been driven by increasing knowledge of the links between silicosis, TB and HIV. South Africa presently has one of the world’s highest TB incidence rates, and transmission is greatly increased among silicosis sufferers.

Health Minister Aaron Motsoaledi recently said the country remains in the grip of a ‘health emergency’ related to TB, with 2 500 to 3 000 cases per 100 000 people. The World Health Organisation’s ‘crisis’ level is 250 per 100 000.

The first major settlement in silicosis litigation came last year, when Anglo American South Africa reached a confidential agreement with 21 former workers from its President Steyn gold mine in the Free State. The miners were represented by the British law firm Leigh Day, which is pursuing a separate settlement via the UK courts on behalf of 4 200 former workers. In March, the group appealed a ruling that UK courts had no jurisdiction to hear lawsuits brought by South African miners.

All parties are now awaiting the outcome of the appeal, which could have significant implications for future litigation. Acceptance of the lawsuit in the UK would raise the profile of the cases internationally, and may convince other former mineworkers to pursue the same avenue. The case has drawn the British parliament’s attention, and earlier this year 43 UK MPs put forward a motion calling for mining companies to pay compensation.

Observers worldwide are watching to see what implications current cases will have for affected workers and the prosperity of the mining sector

In South Africa, Leigh Day and local lawyer Zanele Mbuyisa are also involved in litigation against AngloGold Ashanti, in a lawsuit representing 1 255 former miners with silicosis. The country’s high court recently ruled that the case should proceed without delay, given the risk that some of the claimants might die before the legal process concludes.

Another large class-action lawsuit against a set of 32 South African mining companies is also registering claimants at present.

Represented by Richard Spoor Attorneys, Abrahams Kiewitz Attorneys and the Legal Resources Centre, the suit comprised around 25 000 former mineworkers at the end of 2013. This would be the country’s largest-ever class action – and the number is likely to rise.

There are also efforts to register former miners for state-administered compensation programmes, which have been the subject of criticism for failing to adequately provide and disburse silicosis-related funds. Earlier this year, a Yale University study noted that the shortfall between available funding and required compensation is currently upwards of US$67 million. The study noted ‘separate and unequal treatment of mine workers with occupational lung disease under industry-specific compensation law, in comparison to workers outside of the mining sector’, and argued that ‘improving compensation funding mechanisms and raising benefit levels will likely require multi-stage legislative reform’.

There have nevertheless been increased efforts to register former miners for what compensation there is. In comments to Mining Weekly earlier this year, the Employment Bureau of Africa (TEBA) said it was attempting to trace 200 000 former miners who had been diagnosed with occupational lung disease so that they could claim compensation.

Another large class-action lawsuit, against a set of 32 South African mining companies is also registering claimants at present

According to TEBA CEO Graham Herbert, the maximum payouts ‘were up to US$14 000 per claim’, and that almost a million people stand to receive compensation – including workers from Mozambique, Swaziland and Botswana.

While these cases may appear localised to South Africa, there are implications for similar litigation in other African countries. Some states may lack the legal framework under which silicosis claims can be brought, or state-operated compensation mechanisms may, in some cases, stop former mineworkers from pursuing civil suits. But in a highly-connected world, knowledge of litigation in South Africa is likely to influence the views of mineworkers and legal representatives across the continent, as is an increased awareness of occupational disease.

This is suggested in the popular movement against the poorly regulated use of asbestos in Nigeria, with individual cases already brought by UK law firms on behalf of Nigerians.

Many former workers are now aware of the links between earlier mining employment and lung problems later in life as silicosis can take decades to develop. Across the continent there are generations of African mineworkers who may yet be affected by the disease.

If similar lawsuits are initiated, they could in turn affect gold producers in countries such as Ghana and Mali, or asbestos operations in Zimbabwe – Africa’s only current producer of the carcinogenic fibrous mineral.

Should the current lawsuits in South Africa be successful, they could have a significant financial impact on the local mining sector, as would similar cases in other African states. There are few reliable estimates of what the total damages may amount to – earlier projections ranged from US$46 million to US$100 billion – and it is too early to gauge what the overall effects on the gold sector may be.

Substantial amounts will also be required to make up the shortfall in current state compen-sation funds, and it remains to be seen whether the money will come from taxpayers or the companies involved.

The conclusion of silicosis claims in South Africa will represent an overdue settling of accounts between thousands of affected former miners, the mining industry of the past and the country’s future mining sector. Although it may be costly, a satisfactory settlement is arguably essential to provide the sector with continued social license to operate, at a time when labour relations are unstable. Increased awareness of silicosis is also generating improvements for current workers, with the installation of better methods of dust control, in addition to government programmes to eliminate new cases of the disease by 2030.

Governments and mining companies across the continent must engage equitably with people who may have been harmed by past mining activity, realising that there is increasingly little investor acceptance of those that seek to evade responsibility where it can be proved.

Most importantly, given that silicosis often takes years to emerge, mining companies must improve their current practices where needed, to avoid similar claims being brought by the mineworkers of the future.