In South Africa, the mining industry and the minister both swear allegiance to the concept of economic transformation, while remaining at loggerheads over practical measures to achieve it. The deadlock became even more intractable on 15 June when Minister Mosebenzi Zwane published Mining Charter III. Its previously unseen and more radical provisions horrified the Chamber of Mines, which immediately brought an interdict to prevent the implementation ‘in any way directly or indirectly’, pending a judicial review application.

On 14 July, the chamber announced that it had reached an agreement with the minister that he would not implement the provisions of Mining Charter III until a court had ruled on the chamber’s application. A date for the hearing was set for September.

According to Wandisile Mandlana, an attorney at Bowmans, the chamber’s biggest problem with Mining Charter III is that ‘it came as a shock’. It is substantially different and more onerous than the draft gazetted in April last year. Among other things it hiked the black ownership requirement to retain a licence in the mining industry from 26% to 30% and specified that compliance with this new benchmark was required within 12 months.

Mandlana points out that Mining Charter III had supposedly been the subject of an extensive consultation process. But all submissions to the Department of Mineral Resources were in response to the 2016 version, and the June 2017 version is so different, that it appears to be ‘an entirely new document’.

The chamber argues that not only was there a lack of meaningful consultation but that Mining Charter III’s provisions are either ‘too vague to be enforceable’ or should be deemed irrational. So secretive was the process that even Deputy Minister of Mineral Resources Godfrey Oliphant said, in an interview on Talk Radio 702, that he was not consulted or informed about the changes.

How irrational are the provisions of Mining Charter III? Bruce Dickinson of Webber Wentzel argues that ‘the irony is that Mining Charter III is worse for transformation than its predecessor’. He points out that black, community and employee entities that are supposed to be empowered by the charter will in fact be disadvantaged, adding that it ‘specifies three types of empowerment owners – 14% to black-owned entities and 8% each to communities and employees – and requires that these ownership levels be maintained in perpetuity’.

The problem is the specification, in section 2.1.1.4 of Mining Charter III, that each of these types of entity can only dispose of its shareholdings to another entity of the same kind. ‘Community entities will only be able to sell their shares to other community entities and the same applies to the other types,’ says Dickinson. He points out that this means only very small markets exist in each case, if indeed there is any market at all, adding that ‘these three ring-fenced groupings aren’t able to leverage their holdings for future investment so they’re not very useful’.

Mandlana argues that the increase in the ownership threshold ‘is not in itself a problem – so long as the decision is rational’. He says, however, that he ‘struggles to see how Mining Charter III can be supported on a rational basis’. Mandlana adds that it ‘disregards existing rights’ and does not distinguish between ‘a mining asset that has perhaps three years of life left in it and one that may run for 50 years but imposes the same obligation – and hence costs – on the owners of each’. What it achieves is to change the terms on which mining rights have been issued by administrative decree. This is one of the objections raised by the Chamber of Mines. Tebello Chabana, the chamber’s senior executive for public affairs and transformation, says ‘it amounts to law-making without going through the legislative process’.

The biggest implication for existing empowerment processes is that Mining Charter III simply ignores the industry’s argument that it should include the ‘once empowered, always empowered principle’. In other words, the industry wants to know that once a company has transferred a proportion of equity to designated groups – irrespective of the quantum involved (be it 26%, 30% or another figure) – it will be considered ‘empowered’, even if the beneficiaries sell their shares to non-designated buyers. The minister, however, wants to control who shares are sold to and, therefore, affects the rights of both current shareholders and prospective future owners.

This is not the only example of excessive rigidity that Mining Charter III attempts to impose on the industry. The charter specifies (in Section 2.1.1.12) that ‘black person shareholders shall actively control the trading and marketing of their proportional share of the production’. In other words, a designated shareholder, in terms of the charter, can sell a proportion of mine production separately to the rest of the operation.

Chris Stevens, Werksmans Attorney’s head of mining and resources practice, describes this as ‘an entirely unworkable and nonsensical provision’. He points out that the published version of Mining Charter III is badly drafted and, at many points, incoherent ‘and open to all sorts of interpretations’.

Section 2.1.3, for example, says that sellers of mining assets must grant ‘black-owned companies a preferential and option to purchase’. Not only does this not make grammatical sense, says Stevens, but ‘it gives no sense of how it would work in practice’. In any case, encumbering existing ownership in this way would contravene South Africa’s Companies Act.

Chabana says Mining Charter III is a classic example of regulatory overreach. Dickinson’s colleague Jonathan Veeran agrees.

‘The problem is that it is the Minerals and Petroleum Resources Development Act [MPRDA] that provides the basis of the minister’s powers. But Parliament hasn’t yet passed the [long-awaited] amendment to the act. These amendments would be the legal basis for the new charter. It’s not in place, so the minister’s actions are ultra vires. He has sought to use powers he doesn’t actually have.’

From a legal perspective, says Veeran, it is necessary to pass the MPRDA before enacting the new charter. The 2013 MPRDA Amendment Bill aims to elevate the charter to the status of legislation while giving the minister the power to amend it, but the bill is still before Parliament, so might not pass this year.

Mandlana agrees and points out that the problems go beyond legal process. ‘The charter establishes a Mining Development and Transformation Agency, to be funded by a levy on mining companies.’ However, the Minister of Mineral Resources does not have the power to impose taxes, he says. ‘This is a National Treasury competency, which means that minister is usurping the powers of the Minister of Finance – not to mention Parliament as well.’

Mining Charter III also creates a whole range of new definitions, including that of beneficiaries as ‘black persons’, as well as ‘naturalised black person’, which replaces the term ‘historically disadvantaged’. Chamber of Mines CEO Roger Baxter has pointed out that this would allow the controversial Gupta family to qualify as beneficiaries under the present wording. Mandlana argues that the wording is inconsistent with the MPRDA and, at best, sows further confusion.

It may turn out that not only is the published Mining Charter III impossible to implement but that it is also not legally enforceable. In the meantime, Zwane is sticking to his guns, defending the published version, albeit on principle, not substance. In August he told a gathering of the Black Management Forum that the standing 30% ownership provision ‘does not go far enough’. It is a mechanism to achieve radical economic transformation, he said. However, opposition has been voiced, in some way, in almost every quarter. It is not only the usual suspects such as the Chamber of Mines and the Democratic Alliance, but also the Economic Freedom Fighters, the National Union of Mineworkers, the ANC and National Treasury that have, at the very least, articulated reservations.

It seems to be a case of back to the drawing board. Mandlana argues that while the concept of empowerment is not being contested, the procedural shortfalls and impracticalities require a new process. Dickinson and Veeran suggest that ‘first prize’ would be a new negotiation between the minister and industry but with the ANC leadership conference looming at the end of the year, this might not happen very soon. Yet time is of the essence.

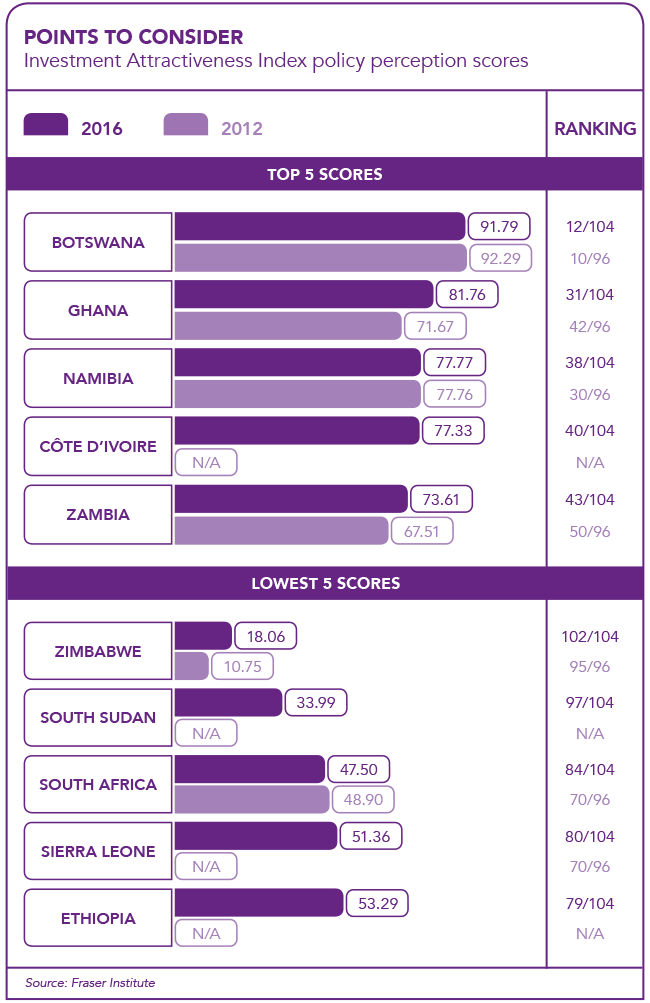

Dickinson says that in 20 years of practice he has not seen the industry ‘as dismal’ as it is at present. While politicians posture, jobs and investment suffer.