Rail systems are among the positive spin-offs of the colonial era in Africa. A glance at a map of the continent shows that these were designed to move goods and people between ports and the interior.

The railway system in Southern Africa focused on the mineral-rich Witwatersrand in South Africa, the country’s ports and Mozambique’s port of Maputo (known as Lourenço Marques when the railway line running from Pretoria was opened in 1895).

The backbone of the railway network ran from Cape Town in South Africa through the British-controlled territories of Bechuanaland (now Botswana) and Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) to the Copperbelt of modern-day Zambia (then Northern Rhodesia). It was also indirectly linked to other ports in the British colonies.

Railway journeys in the region became legendary. Writers and travellers recorded their experiences as steam locomotives pulled ornate wooden carriages along railway lines that passed through the Cape mountains and across the arid Karoo landscape. The spectacular girder bridge, high above the Zambezi river at Victoria Falls, featured in writings of early travellers. More recently, it was the scene of decisive and historic political discussions between the former Rhodesian government and its successors.

Pulled by Garratt steam engines, heavily-laden coal trains thundered down the escarpment, delivering coal from the Witbank collieries to Lourenço Marques for export. Meanwhile the busy Durban-Johannesburg line carried all types of cargo – and full container trains have been moving in both directions since 1977.

With most passengers switching to air and road transport in more recent times, and much cargo now moving from door to door on trucks, post-colonial railway construction projects have mostly surrendered the need to export bulk minerals or agricultural products.

Built over several decades and completed in 1929, the Benguela railway was key to the export of copper and other minerals from the Zambian Copperbelt and the DRC’s mineral-rich Katanga province.

The railway was largely destroyed during the Angolan civil war, and reparation work was focused on making only the Lobito to Luau (near the DRC border) stretch operational. Ongoing conflict in the country will delay the complete restoration of the line, which means Katangese and Zambian mines will not be able to use it for export, which is vital for earning foreign revenue, especially as the country still struggles with internal political strife. As the railway remains unconnected to Zambia, it further prevents the use of transcontinental links to Dar es Salaam and Beira.

These challenges bring into sharp focus a project between the NorthWest Railway Company and South African-based shipping and logistics company Grindrod. It aims to build a new direct railway link from Chingola and three other mining towns in the Zambian Copperbelt, to the Angolan border. It will connect to the Benguela railway, thus obviating the troubled DRC.

Once the two-phased, US$990 million project has been completed, Central Africa – and particularly Zambia – will have renewed access to the Atlantic seaboard and Lobito. This will provide significant impetus to economic development in that remote area of Zambia, which is rich in mineral and agricultural potential.

Grindrod’s involvement in the project will include rail construction; the building, supply and leasing of locomotives and other rolling stock; and managing railway operations.

When completed, this new infrastructure will significantly improve freight transport access into Central Africa, and stimulate employment in Zambia’s North-Western province.

Despite accelerating upgrades and new railway systems coming into service or being planned, rail infrastructure cannot handle the volumes

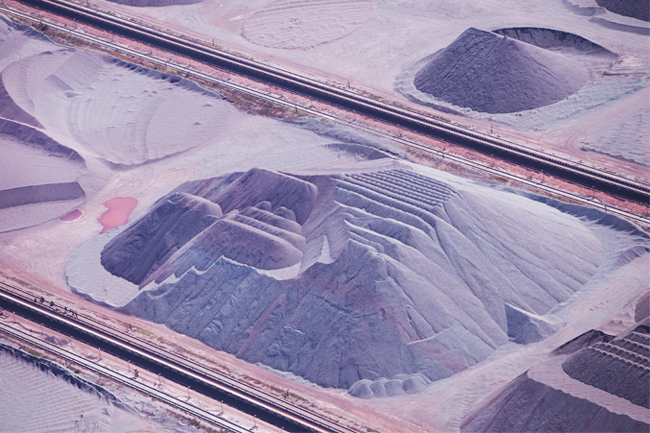

In South Africa, several upgrades over the years have helped the Sishen-Saldanha Bay railway keep pace with the demand for the high-grade ore exported via the west coast port. The most recent upgrade, which was completed ahead of schedule in 2011, now allows about 60 million tons of ore to be railed.

This includes about 9 million tons from Kumba’s new Kolomela mine at Postmasburg in South Africa’s North West province, which is linked via a 36 km extension to the existing ore line from Sishen.

The line has been so efficient that in excess of 11 million tons of ore came from the new mine – 2 million tons more than expected. Transnet Freight Rail has provided a capital investment of more than US$400 million for additional rolling stock to upgrade electricity infrastructure and extend the rail link.

The overall harbour development plan for Saldanha Bay is ambitious and includes costly ship and oil rig-repair facilities that centre around a large dry dock; more general-purpose quay space; an oil-blending facility; and extensions to the iron-ore export terminal to cater for any further growth in exports.

Figures of around 88 million tons of ore per annum have been mentioned. But for this to take place, the carrying capacity of the main railway line between Sishen and Saldanha Bay will need to be increased. This can be achieved by either doubling the number of passing sidings on the line or laying a double line for the full distance. It is a costly exercise, although the largely flat terrain decreases the cost of railway construction. Progress was being made until the environmental impact assessment was put on hold in early 2014, which effectively halted the project.

Since the inception of the ore and oil terminals at Saldanha Bay, environmental issues have dominated discussions regarding the port’s expansion. A national park covering the southern half and western side of the lagoon, aquaculture beds to the north of the terminal and the busy leisure boating and fishing sector have added weight to arguments against further expansion.

Antagonists point to the iron-ore dust that pervades the land around the harbour area, while the seabed has also been affected by it. The presence of this dust has been raised during exploratory talks between ship and rig-repair companies, who say that certain welding technology is incompatible with iron-ore dust because such operations need a clean environment to obtain the best results.

To their credit, Transnet National Ports Authority, which controls the harbour and terminal, has taken significant steps to ensure that the dust is kept to a minimum, and harbour development plans have taken this into account. Until these peripheral matters are resolved, further expansion of the ore terminal is doubtful – and this will be to the detriment of local labour and the wider economy.

By signing an agreement to build the 1 500 km Trans-Kalahari railway earlier this year, the governments of Namibia and Botswana have affirmed the need for another significant railway development in Southern Africa. They are prepared to involve private investors to help fund the US$9.2 billion cost of the project.

Driving the railway plan is landlocked Botswana’s need to export as much as 90 million tons of coal per annum from its large coalfield in the south-east, with much of it going to power stations in China, India and Europe via a new deepwater coal terminal at Walvis Bay in Namibia.

The proposed railway would cross central Botswana and link to the existing Namibian line at Gobabis. A significant upgrade to the Namibian railway system would be required to handle the regular movement of heavy-haulage, high-speed coal trains.

To ship coal to Asian terminals, capesize bulk carriers of about 300m in length with 18m draught would be needed to make the ocean leg economical. A new coal terminal with the required depth of water, length of quay to accommodate at least two ships at a time, and large stockpile area will have to be constructed. But the proposed Walvis Bay terminal will be inadequate to export the envisaged volume of coal, which will require 10 ships a week. Botswana may have to rely on South African harbours to export some cargoes to the East.

African economies will see an average growth of 4.7%, compared to significantly lower growth rates in Europe, Japan and the US

An alternative, which is preferred by a few in Botswana, is to use a proposed port that can be constructed south of Maputo at Ponto Techobanine. Coal brought via a dedicated heavy-haulage railway from central Botswana via Zimbabwe can then be exported.

Support from the three countries involved in the project was initially enthusiastic, but seems to have dwindled. The overall – and very ambitious – plan for a railway system going east to Ponto Techobanine and west to Walvis Bay will not be limited to coal exports as it will give Botswana vital, direct access to the Indian Ocean for general trade with Asia. The Walvis Bay link will also enhance trade with Europe and the US.

Brazilian mining giant Vale is currently busy with a US$1.8 billion project to construct a 912 km rail link from its colliery at Moatize in Tete province via Malawi to Nacala, a deepwater port on Mozambique’s north coast.

Once operational, the project (which includes various upgrades to the port) should see some 18 million tons of coal exported per year.

A closer option to help export Tete coal involves a proposed railway to Macuse (near Quelimane) where a deepwater port is planned. The project has already been signed over to an Italian-Thai consortium, but after costs were re-evaluated, it showed that the project had escalated from US$3 billion to US$5 billion. Since major financial issues have to be addressed, the project seems to have stalled.

The UN’s Department of Economic and Social Affairs states that African economies will see an average growth of 4.7%, compared to significantly lower growth rates in Europe, Japan and the US. As mining and industrial development continues across the continent, road transport becomes even more important.

Despite accelerating upgrades and new railway systems coming into service or being planned, rail infrastructure cannot handle the volumes of freight being moved to and from ports, not to mention the increasing volumes of intra-African trade.

Up to 80% of goods moved around Africa do so by road. In addition to industry and infrastructure, growing African economies have also created a burgeoning and consumptive middle class, which has increased retail demand and made supply chains more reliant on road freight.

As road-based logistics experts grab the chance to service this market, some companies have chosen to operate regionally while others have specialised in moving certain commodities. Among those that have taken the latter course is Johannesburg-based Cargo Carriers, which has achieved significant growth in the sub-Saharan African fuel, mining chemicals and bulk dry powder industries. In the face of the rapidly expanding construction sector, the firm has developed a niche market to move bulk dry cement.

It recently acquired a majority stake in the Zambian haulage company BHL, which gave Cargo Carriers access to an expanding market in Zambia, Namibia, the DRC and Angola. Initially focused on the mining and chemical industries, BHL is successfully expanding into the manufacturing and agricultural sectors.

While Southern African railways will provide the backbone for heavy, long-distance haulage, road transport has filled niche markets. Given its flexibility to serve greater areas and provide door-to-door services, it is the preferred mode of transport for some commodities.

Since expansion of mining, agriculture, industry and general commerce is a hallmark of the current African scene, all forms of transport are destined to play an even greater role in helping stimulate further growth and development in this rapidly evolving continent.