In June it became apparent that the total volume of gold mined in South Africa had fallen below Ghana’s output for 2018. This rendered South Africa only the second-biggest gold producer on the continent and it was widely reported as some sort of metaphor for the ills of South African mining more generally. News agency Bloomberg described it as ‘yet another humiliation’.

Yet the South African mining industry, while depressed, may well have turned the corner. A lot of the optimism evident in 2019 has to do with new political leadership and a much warmer relationship between the industry and government.

Speaking in February, Minerals Council South Africa (MCSA) CEO Roger Baxter noted that ‘the business and mining environment has changed beyond recognition’ in the past year. He argued that ‘instead of deep pessimism, there is today a knowledge and recognition that government leadership is committed to resolving the country’s myriad socio-economic challenges with integrity. For the mining industry in particular, the minister has adopted a similar approach’.

The object of this effusive praise is Gwede Mantashe, South Africa’s Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy, who replaced the controversial Mosebenzi Zwane at the end of February last year. The MCSA said that the reappointment of Mantashe after the country’s general elections in April ‘is a key signal of the seriousness with which the president [Cyril Ramaphosa] is taking the restoration of investor and business confidence in mining’.

While there are outstanding issues between Mantashe and the MCSA, which represents up to 90% of the South African minerals production by value, the minister’s budget vote speech in July was a validation of the faith the industry has placed in him. In typical upbeat fashion, he referred to mining in South Africa as ‘a sunrise industry’. More significantly, he revealed practical measures to address some of the main shortcomings in the enabling environment.

Mantashe announced his intention to improve the mining licensing system. There were repeated allegations and inefficiency under his predecessor. Mantashe had already acted, mostly below the radar, in removing some of the most notoriously corrupt officials. Now he is moving on to address the long turnaround times to process applications. ‘Time frames must be short, without having to effect major legislative amendments, by adopting more effective and efficient internal processes,’ he said.

Slow processing of licence applications has inhibited the upstream industry especially. As of early last year, diamond giant De Beers had received just 16 exploration licences out of the more than 50 it had applied for, after waiting more than two years. Exploration geologist John Bristow comments that ‘this should be a straightforward administrative function. It should have taken a few hours’.

One of the areas most affected by past uncertainty and regulatory inefficiency in the South African jurisdiction is greenfield exploration. South Africa absorbs around just 1% of global spending on this activity – although De Beers’ use of their new licences in 2019 may have doubled the figure – and Mantashe wants to raise this to US$10 billion per annum, which equates to 5% of global exploration share.

To this end, the department will be investing in a geological mapping programme. South Africa’s geological maps are not only out of date but are also notoriously inaccessible. ‘In Namibia, Botswana and Mozambique, you can access geological maps on the internet,’ says Bristow. ‘South Africa has fallen far behind in this area and our cadastre, which should show who owns what on a series of maps, is no longer up to standard.’

Bristow, who is a well-known advocate of the junior mining sector, is pleased that this area has received attention in Mantashe’s budget vote speech. However, he has reservations about its practicality. In Bristow’s view, ‘these are big ideas. I’d prefer to see a few more practical baby steps’.

He suggests, for instance, that greater use be made of existing private-sector information. ‘An operation like Kumba in the Northern Cape is sitting on a huge pile of data. What I’d like to see is the Council for Geoscience accessing resources of that sort.’

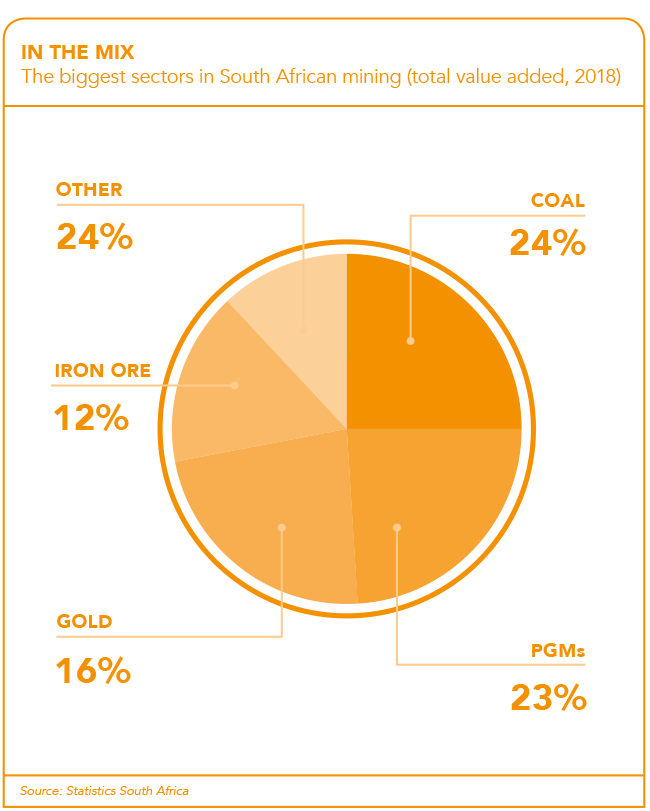

Although relations between the minister and the industry have improved, they do not see eye to eye on everything. A court challenge by the MCSA to the minister’s BEE Mining Charter is still outstanding although there have been no new statements by either party on the issue for several months. Even if Mantashe’s approach makes a big difference, South African mining is still near the bottom of a decade-long trough. A Statistics South Africa press release published in June indicates that minerals production was down 10.8% for the first three months of the year, after falling 1.6% in 2018.

In a February 2019 report, McKinsey comments that ‘over the past decade, the South African mining sector has stagnated. In real terms the sector’s value declined by 4% between 2007 and 2017. In fact, 47% of South African mining jobs, along with 42% of revenues, are in the vulnerable bottom quartile of global cost competitiveness’, according to the international consultancy.

However, the picture varies depending on which mineral sub-sector is concerned. While gold production was down 24.4% in May this year (compared to a year ago) and there were also falls in production of diamonds (30.7%) and iron ore (5.2%), other minerals have done better, according to Statistics South Africa. Coal production was up by 8%, platinum group metals by 6.8% and manganese ore by an impressive 29.3%.

While annual production comparisons refer to a contrast between two snapshots and can be misleading, the decline of gold is deep and structural. In contrast to dropping South African production, gold output in Ghana jumped 12% in 2018. Mantashe argues that in South Africa, ‘gold is an old sector and naturally it will decline’. He suggests that ‘new minerals that are discovered are becoming more important’. But there is more to the issue than an ageing resource simply being played out.

South African gold’s decline is not simply a geological challenge. The industry’s two biggest cost factors are labour and electricity. Labour accounts for 53% of total operating costs, a far greater proportion than in any other mining sector. The cost of labour has steadily climbed over the past 20 years. ‘Over more than two decades, labour costs have continued to increase at well above inflation,’ notes a July 2018 industry fact sheet. Between 2006 and 2016, labour costs increased by 18% while productivity declined by 3%, it adds.

With electricity, the problem is not only soaring costs (since 2008, the price has increased more than 500%) but also reliability of supply. Renewed load shedding by national power utility Eskom in the early months of this year was the main reason for the dramatic collapse of gold output.

Mantashe now has responsibility in that area too. When Ramaphosa restructured the government after the April elections, the energy portfolio was added to Mantashe’s responsibilities. This doesn’t mean his primary responsibility is sorting out Eskom’s cash crunch – that vests with Pravin Gordhan’s Department of Public Enterprises – but having a mining-savvy minister in energy is considered a positive factor by the industry.

In his budget vote speech, Mantashe claimed that South Africa’s policy and regulatory framework is ‘stable and predictable’. Indeed the gazetting of the third iteration of the Mining Charter in September last year appears to have been the reason for the country’s improvement in the Fraser Institute’s mining policy attractiveness rankings. In the rankings for 2018 (released in March 2019), South Africa placed 56th out of 83 countries rated. For 2017 it was 81st out of 91.

Mantashe listed new mining investments, totalling R45 billion, in the past year as evidence that South Africa is ‘an attractive destination for mining investment’. These include the first phase Vedanta Resources US$1.6 billion zinc mine and smelter, at Gamsberg in the Northern Cape, which opened in February. It is intended to be the world’s largest zinc mining and processing complex, and has been a decade in planning and development.

The Gamsberg project does indeed read like an endorsement of South Africa’s prospects. Vedanta stepped in and acquired the resource after the previous owner, Anglo American, had failed to develop it. Economist Iraj Abedian is of the opinion that the ‘story’ illustrates that ‘with proper and professional collaboration between the private sector and state departments across all spheres of governance, South Africa can achieve effectiveness and efficiency in the administration of its mining laws and regulations’.

It may well be that Gamsberg is more the face of South African mining’s future than the declining gold industry. It suggests a movement away from precious metals and towards industrial commodities. It also shows that mining companies and government can collaborate. That is why, on the evidence of statements by the MCSA, South African mining is suddenly looking a lot more optimistic than it has for years.