South Africa’s mining sector has endured a torrid 2023 as global mineral prices retreated strongly from the highs of 2021 and 2022. While observers expect some commodities prices to strengthen in 2024, they are not optimistic about likely trends for three of South Africa’s main minerals – coal, iron ore and platinum. After two sparkling years of performance, where minerals exports were described as having ‘saved the South African fiscus’ mining companies faced much more difficult conditions in 2023.

Figures captured by consultancy PwC show that profits for 29 of South Africa’s biggest miners almost halved in 2023, down to US$5.5 billion compared to US$10.6 billion in 2022 and an even more impressive US$10.8 billion in 2021.

‘Mining is a cyclical business,’ points out Paul Miller, CEO of South African mining investment company AmaranthCX. ‘At the moment, most commodity prices are low because China is flatlining and interest rates are high all over the world.’

‘However, at some point demand is going to revive and so too will mineral prices and the fortunes of mining companies.’ His main concern is that exploration spending is not going into South Africa on any sort of scale. ‘When prices recover, there will be new mine developments, many of them in future-facing minerals like copper, lithium and cobalt. South Africa simply doesn’t know what we have under the ground any more. We’re not exploring,’ he says.

The other big issue is that there is going to be a lot of pain in the interim. ‘We have a policy that we don’t run loss-making businesses,’ says Sibanye-Stillwater CEO Neal Froneman. He is particularly concerned about the platinum sector, which faces not only low prices but a perceived existential threat from electric vehicles.

Froneman notes that ‘we will probably have to go through further shaft closures if prices deteriorate from the current levels. The socio-economic impact of retrenchments is very hard and heavy, and it’s the last thing we want to do’. The potential job losses come at a time when labour relations in the platinum and gold sectors are fraught.

A new tactic, where workers remain underground in protest, has yet to be properly understood. The phenomenon, which occurred at least four times in the closing months of 2023, has been condemned by mine managements as ‘coercive’. Some reports suggest this is the result of a standoff between rival labour unions.

Mining analyst Peter Major points out that declining commodity prices coincide with other problems, notably electricity supply uncertainties and the logistics logjam around Transnet’s bulk ore lines – coal to Richards Bay and iron ore to Saldanha. ‘Kumba Iron Ore currently has to stockpile 9 million tons, which it simply cannot get to the coast to export,’ he says.

This is about one-fifth of the Sishen-based mine’s total annual production and is, in Major’s view, the reason Kumba announced towards the end of last year that it was deferring ZAR2 billion in future investment.

There may, however, be a ray of hope when it comes to logistics issues in the coal sector. The impact of cable theft and a shortage of locomotives (and spares) on the dedicated Witbank-Richards Bay coal export line has seen coal exports plummet to 50 million tons in 2022 and a December forecast of 47 million tons in 2023, the lowest figures since 1993. The Minerals Council South Africa (MCSA) estimated that logistics were the reason for South Africa’s coal miners losing out to the upside of ZAR50 billion in 2022 (and ZAR35 billion in 2021), when prices soared in the wake of European energy sanctions against Russia.

Thermal coal exporter Thungela announced that it had ‘curtailed production at three underground sections’ and had been forced to stockpile 2.7 million tons at site. This, the company said, ‘is equal to nearly one quarter of annual export sales’.

However, the problems at Transnet have been recognised by government. President Cyril Ramaphosa announced the formation of a National Logistics Crisis Committee in his State of the Nation Address in 2023. The committee, which brings together senior government and private-sector representatives, may be starting to have an impact. The top three senior managers at Transnet have been replaced, on a temporary basis, and coal miners have said they are stepping up to fund spare parts for locomotive repairs and refurbishments. More than 200 locomotives have been standing idle as a result of a tax dispute with a Chinese supplier.

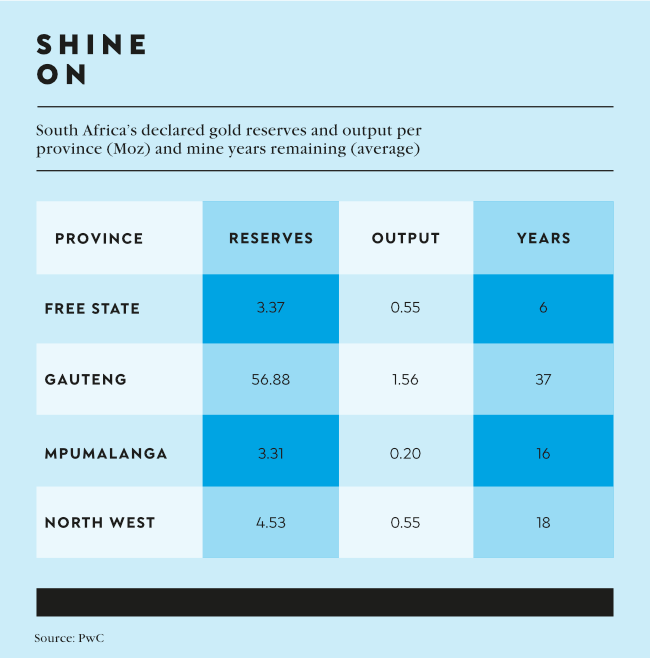

Yet while global headwinds have hit platinum group metals (PGMs), iron ore and coal miners in 2023, South Africa’s gold miners have provided a bright spot in the gloom.

The gold narrative has been gloomy for many years in South Africa. Tonnages mined have fallen year after year for five decades, leaving the country, once indisputably the world’s gold mining champion, ranked 10th in the world and second in Africa, behind Ghana. In a move that seemed to symbolise the decline of South African gold mining, AngloGold Ashanti moved the company’s primary listing from Johannesburg to New York in 2023. The miner has no remaining gold assets in South Africa, having sold its last two ageing mines, Mponeng and Moab Khutsong, to Harmony Gold Mining between 2018 and 2020.

Yet gold mines in South Africa bounced back strongly in 2023 on the back of a robust performance for the ‘safe haven’ metal in the face of global political and economic uncertainties. In the latest issue of its annual publication, SA Mine, consultancy PwC ranked Gold Fields as the top company by market cap on the JSE (at ZAR234 billion), rising from fourth place last year, and displacing Anglo American Platinum at the top of the rankings. South Africa’s other major listed gold miner, Harmony Gold, is ranked sixth, up four places from last year.

The share price of another South African gold miner, DRDGOLD was one of the top-performing stocks on the JSE, up 63% at the time that PwC’s SA Mine report was published. But DRDGOLD also represents one of the limitations of the gold sector in South Africa.

Although listed on the mining board, it is a surface-based tailings retreatment operation. It essentially reprocesses old mine dumps and slime dams to extract gold that was originally missed by older, less-precise technologies. The company, part-owned by gold and platinum giant Sibanye-Stillwater, is a product of South Africa’s gold mining past, not its long-term future.

Nevertheless, there is new investment happening in the South African gold sector. Gold Fields expects its South Deep mine, the most recent and most mechanised gold mine in South Africa, to continue producing for another 95 years. But even the older, supposedly close to worked-out deep shafts may have more life left in them than many expect, especially if the gold price holds up. Harmony, which owns South Africa’s second-, third- and fourth-most productive gold mines, said last year that it aimed to deepen its flagship Mponeng mine, already the deepest in the world. ‘My personal belief is that it will be a mine that’s got a very long life; it’s very high grade ore and it’s certainly something that’s worth pursuing,’ Harmony CEO Peter Steenkamp told Reuters. Prior to the mine’s sale to Harmony in 2022, AngloGold Ashanti had completed only the first of a planned two-phase expansion process.

One of the major headwinds facing the mining industry is energy security. Opinions are divided over whether there is a realistic chance of load shedding – the curbing of supply to protect the stability of the system – being reduced by state initiative.

What is clear though is that the Stage 5 and Stage 6 load shedding experienced repeatedly in 2022 and 2023 resulted in costs for miners. Nedbank has argued that mining lost 6% of output in 2022. But the problem has prompted a proactive response from the mining industry. Following the lifting of a cap on embedded generation in 2022, most bigger mining operations started to implement their own solar installations.

At South Deep, Gold Fields is already drawing power from its Khanyisa solar plant. Intended to provide 50 MW, the plant will save South Deep ZAR123 million a year and massively reduce the mine’s carbon footprint.

According the MCSA, 29 mining companies in South Africa have embarked on 89 projects intended to deliver 6 500 MW of renewable energy. When the Electricity Amendment Act is passed, they will be able to sell surplus energy into the grid, thereby helping address a critical national constraint.

Many miners in South Africa are in survival mode but the signs are that they are hunkering down and doing what they need to do to get by. When global interest rates come down and the Chinese economy starts to move again, they are likely to be leaner and better positioned to grow.