A ripple of relief went through the South African mining industry in late February when President Cyril Ramaphosa announced the replacement of Jacob Zuma’s compromised Mineral Resources Minister, Mosebenzi Zwane. The new minister, Gwede Mantashe, is a political heavyweight – having recently served as secretary-general of the ruling ANC – and has considerable experience in the mining trade unions.

Mantashe has a tough job ahead. Parts of the industry – notably underground platinum mining and thermal coal supplies to energy parastatal Eskom – are in trouble. The regulatory framework as well as the relationship between the industry and the government were casualties of his predecessor’s erratic tenure, with the result that investment in new mines, exploration and projects dried up almost entirely. Nevertheless, even this early in Mantashe’s tenure, some promising green shoots are visible.

Generally, the industry has been under considerable pressure, shedding 70 000 jobs (15% of its labour force) since 2012. But internationally, the revival of mineral prices is continuing and, if Mantashe makes the right moves, will support a reformed South African industry.

The Minerals Council of South Africa (formerly known as the Chamber of Mines) describes Mantashe as ‘a man of integrity and dignity … with a sound and fundamental knowledge of the industry’. Meanwhile, mining executives who encountered him as during his time with the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) have described him as ‘an extremely tough negotiator’.

Mantashe’s challenge is to restore confidence in the enabling environment for mining and, in the immediate future, secure agreement over the sector’s BEE charter. The current charter is intended to replace the 2010 version and is critical in setting the levels of black, indigenous ownership required of mining licence holders.

Mantashe declared that he would drive a process to produce a final, agreed Mining Charter within three months. During its dispute with Mantashe’s predecessor, the mining industry had sought a declaratory order from the High Court over the issue of whether once black ownership of a company had reached the levels prescribed in the 2010 charter (26%), the firm could be regarded as permanently empowered.

At issue are the black partners that cash out while the mining asset is still viable. The government’s position was that the company needed to ‘top up’ black ownership, while the industry preferred the opposite ‘once empowered, always empowered’ position.

The industry greeted Mantashe’s appointment by suspending the High Court application. Yet once it became apparent that the new minister did not intend renegotiating the entire charter but instead had chosen to simply negotiate the points of difference in Zwane’s original draft, it reactivated the process. The court ruled in early April in favour of the ‘once empowered, always empowered’ principle. Mantashe announced that he would not contest this matter.

However the court also ruled, almost incidentally, on the legal status of the charter. It found – in a split (two-to-one) decision – that it is merely aspirational, has the standing of a policy paper or guideline, and is thus not a legally binding requirement.

As the charter had previously been regarded by the department as its strongest legal instrument, Mantashe had no alternative but to appeal. This may play havoc with his three=month deadline as legal experts suggest it will require an 18-month to two-year process.

Mantashe is going to have to finesse the process, possibly separating the issue of the charter’s legal status from negotiating agreement on the actual document. This issue may well prove to be the make-or-break factor in determining the success of his tenure.

It’s not going to be an easy road. Trade union rivalries are likely to complicate the charter process. Like Ramaphosa, Mantashe is a product of the NUM, and its rival – the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (Amcu) – has argued that his personal history may make him too partisan to deal with them. Amcu leader Joseph Mathunjwa welcomed the dismissal of former minister Zwane but somewhat ominously stated that Mantashe has ‘his own skeletons in the closet’.

The union had previously warned that a Ramaphosa government could lead to austerity and job losses. Amcu is the majority union on South Africa’s platinum mines and has a strong presence in the gold subsector.

There was a profound re-alignment within the trade union space during the latter years of Zuma’s presidency. A leftist formation, the South African Federation of Trade Unions (Saftu) has been spun out of workers who left the once dominant Congress of South African Trade Unions, arguing that it had effectively become a creature of the ruling ANC.

Far from reconciling with the Ramaphosa government, the new federation has set out to consolidate its place on the political left by opposing South Africa’s new minimum wage legislation (which Ramaphosa was instrumental in formulating). Amcu is not formally tied to Saftu but it has similar ideological concerns and could be swept up in its struggles, with consequences for the mining industry. The trade union experience of the new minister is likely to be tested by these dynamics.

The charter aside, there have already been some promising developments in regulatory matters. Under Zwane, De Beers applied for and failed to get the 54 prospecting licences it needed to augment current production and locate new deposits. But as Mantashe was preparing to assume office, the Department of Mineral Resources relented and granted 16 licences. ‘The wind of change is indeed blowing,’ says De Beers CEO Phillip Barton.

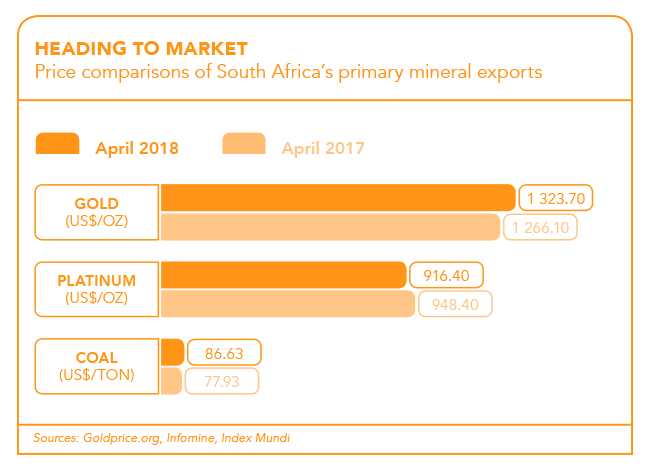

International events will support a reformed South African industry. In mid-2018, commodity markets are once again looking strong. Indeed, in the view of US Global Investors’ Frank Holmes, mineral commodities ‘are flashing a once-in-a-lifetime buy signal’. It has to be said that this optimism is not universally shared, with the World Bank’s April 2018 Commodities Price forecast looking very flat for the next few years and even declining for some minerals, including coal and iron ore.

In any case the positive outlook does not apply equally to all minerals. Holmes’ bullishness is mostly in reference to energy commodities and gold. He is not alone. In April, Goldman Sachs commented that ‘the case for owning commodities has rarely been stronger’. The US-based investment bank was expecting gains in oil and aluminium in particular to top 10% in 2018.

The major anticipated driver of mineral prices, for both Holmes and Goldman Sachs, is China’s Belt and Road policy. That policy revolves around a massive increase in communications and transport infrastructure – including roads, high-speed railways, airports, harbours, dams – designed to connect China’s economy to the world. It will affect as many as 68 countries and 62% of the global population.

The Belt and Road programme is still in its infancy. The US$180 billion invested so far seems an impressive sum. But it is dwarfed by the estimated total cost of between US$4 trillion and US$8 trillion, which is 12 times more, in real terms, than the Marshall Plan that revived European economies after the Second World War, according to BHP.

South Africa’s main mining subsectors – platinum, coal, iron ore and gold – each face their own opportunities and constraints. Eskom’s financial stress means it has not been able to invest in the ‘tied’ mines that supply its power stations with coal. The result is the re-emergence of the possibility of an undersupply – the dreaded ‘coal cliff’ – which might have adverse national implications for energy security.

However, the new government will already be alert to the dangers Eskom’s finances pose to the national economy.

In January, even before becoming national President, Ramaphosa, as Deputy President, ordered the reconstitution of the parastatal’s board in order to reintroduce adequate standards of corporate governance into its operations. A rational and honest Eskom is an essential first step towards the sectoral restructuring that South Africa’s tied coal producers require.

The platinum sector is particularly stressed, given not just South African issues but also a global oversupply partly related to technical changes in the global economy, especially the rise of electric and hybrid vehicles. An April report by investment bank JP Morgan Cazenove argues that 2.6 million ounces or 60% of South Africa’s production of platinum is unprofitable. But the problem can be expected to unwind as lower global production levels push prices up again in 2020.

Unfortunately, the bank cautions, most of that supply cut will come from South African producers, who will have to close and moth-ball shafts and retrench workers.

Those platinum mines that survive the contraction will be in a position to thrive after 2020. This is an area where the industry itself needs to be active. Sibanye-Stillwater’s all-share takeover of world number-three platinum producer Lonmin could generate ZAR1.5 billion in savings by integrating the adjacent Rustenburg operations.

Mantashe has voiced approval of Sibanye-Stillwater’s management style, noting that ‘there is a lean management structure [on the company’s gold mines] and a lot of emphasis on the mines’. He has said he suspects the takeover ‘will work’.

The Lonmin deal is just one example of an area where the new minister and the industry are in the process of finding one another. However, it remains to be seen whether the recent fatal accident at Sibanye-Stillwater’s Driefontein shaft will have an effect on the fledgling relationship.

That said, Mantashe is proving a great deal more receptive than his predecessor and, if he maintains momentum, the schism between government and the big mining companies may rapidly be healed. The industry needs to seek and use these opportunities.