Driven by record or near-record high international prices for ‘future-facing’ decarbonisation metals – lithium, nickel, cobalt and copper – as well gold and (contradicting the ‘green’ narrative) coal, gas and oil, the recent commodities surge has commentators talking about a new super-cycle. But matters are more complex than a simple onward and upward trajectory, with different drivers affecting different mineral commodities and jurisdictions.

The last super-cycle was good for sub-Saharan Africa, with the exception of South Africa, which largely missed out. In the decade-and-a-half to 2014, African mining jurisdictions had boomed on the back of China’s massive expansion after joining the World Trade Organisation at the end of 2001. The value of China’s trade with Africa soared from US$4 billion in 1996 to US$200 billion in 2014, a 50-fold increase.

In 2014, however, commodity markets suffered a massive downward correction, starting with a 70% plunge in the oil price. It soon spread to other mineral commodities, with global mining companies being forced to cancel exploration and development spending and dispose of assets on a massive scale. Anglo American put coal, iron ore, manganese and nickel assets up for sale as part of what one newspaper described as a ‘shrink to survive’ strategy.

The correction altered the continent’s prospects. ‘External tailwinds have turned to headwinds for Africa’s development,’ according to the World Bank. But now, the post-2014 cutbacks are an important factor driving the price surge because they eventually induced a scarcity of supply in many mineral commodities.

When the COVID pandemic retreated and the global economy began to bounce back, there were inadequate quantities of most minerals being taken out of the ground. Jeff Currie, global head of commodities research at investment bank Goldman Sachs, pointed out in February that mining-investment levels have been low since the downward correction of 2014/15. ‘Of the 27 commodities that make up the Goldman Sachs index, every single one of them is in a deficit,’ he said. Established miners did very well in 2021. The top five Western diversified miners (BHP, Rio Tinto, Vale, Glencore and Anglo American) earned a profit totalling US$82 billion in the first half of 2021.

Although margins slipped a little in the second half of the year, commodity prices surged again after Western sanctions on Russia, following the invasion of Ukraine in 2022, which removed substantial chunks of palladium, platinum, gold and coal from the market, and may heavily impact diamond supplies. The question facing mining companies as they try to decide what to do with these profits is whether they are seeing a bounce-back from the lows of the pandemic or the beginnings of a new super-cycle driven, in part, by a boom in decarbonisation metals that will last a decade or more?

Some are in no doubt. Evy Hambro, global head of thematic and sector-based investing at BlackRock (the world’s biggest investment firm with US$10 trillion under management), said in January that ‘we’ve got a decade worth of high rates of investment into infrastructure [ahead] as the world seeks to decarbonise. What we’re likely to see is strong demand that will keep prices at very, very good levels for the producers for many years into the future. And that could be decades’.

Currie agrees. ‘While supply is very constrained, there has been a structural change in demand,’ he says. For metals alone, ‘the core of the story is the war on climate change […]. In this decade alone, you’re going to see upwards of US$16 trillion of additional capex on green investments. That’s the equivalent of […] about what China spent in the 2000s. Over the next decade, it’s two Chinas’.

Other observers see greater complexity in the situation. Mike Townshend of Cape Town-based Foord Asset Management observes that ‘there’s no agreed definition on what a super-cycle is. My definition is that it has to be a sustained period of elevated prices – at least 10 years – driven by a structural change in demand’. He reckons the last super-cycle was driven by ‘a significant population shift in China’, which produced a massive infrastructure boom there. ‘Just think of all the apartment blocks, airports, railway lines, roads and power stations that had to be built.’

Townshend points out that ‘high prices generally draw new supply into the market’. This is likely to be happening right now. However, he adds that ‘you are not going to see all commodities rising equally from these elevated 2021 levels’. His caution is shared by some of the big miners.

Commenting on the second half of 2021, Huw McKay, VP of market analysis and economics at BHP Group (the world biggest diversified miner by market cap), said that ‘the half-year was characterised by yet more extraordinary volatility, but instead of a shared, albeit staggered recovery pattern, highly idiosyncratic trends have emerged’.

Yet McKay does generally accept that after a mild correction in 2022, long-term prospects are good in many areas. ‘What is common across the 100 or so Paris [climate change agreement] pathways we have studied is that they simply cannot occur without an enormous uplift in the supply of minerals such as nickel and copper,’ he says.

Although mining investment into the continent was one of the casualties of the 2014 drop in prices, some diversified miners have continued to invest in big future-facing commodity projects.

BHP itself was inactive across the continent since it spun off all its African assets to form South32 in 2015. But it announced earlier this year that it had invested US$100 million in a huge Tanzanian nickel project (Kabanga) and has also been looking for some sort of involvement in Ivanhoe’s Kamoa-Kakula copper mine in the DRC. Both projects are directly confronting resource nationalisms by including processing facilities.

BHP CEO Mike Henry says he is ‘confident we have the capabilities to pursue opportunities in what some would see as tougher jurisdictions, but the size of the opportunity needs to be commensurate with the increase in management effort that is going to be required’. It is widely understood that many African countries are among Henry’s ‘tougher jurisdictions’. In Guinea, Rio Tinto is still struggling to develop the huge Simandou iron-ore deposit with its estimated reserves of 2.4 billion tons. After a saga that goes back a decade or more, a new military junta seized power in the West African country last year and has set out to change its relationship with foreign mining companies. The junta wants miners to build the export rail road to its own port of Conakry, rather than using the (shorter and cheaper) planned route via Liberia’s Nimba.

Gold miners have battled for several years with localisation demands in Tanzania, with Barrick Gold, one of the two big foreign investors in the jurisdiction, resolving matters by selling 16% of its three mines to the government in 2020. On the other hand, a company with a big appetite for risk, Endeavour Mining, which has gold-mining investments in Burkina Faso, Mali and Côte d’Ivoire, has grown sufficiently to find itself listed in the (London) FTSE 100 index for the first time in March. The other mining companies represented on the FTSE 100 continued to outperform the index in 2022, an outcome that some interpret as supporting the super-cycle idea.

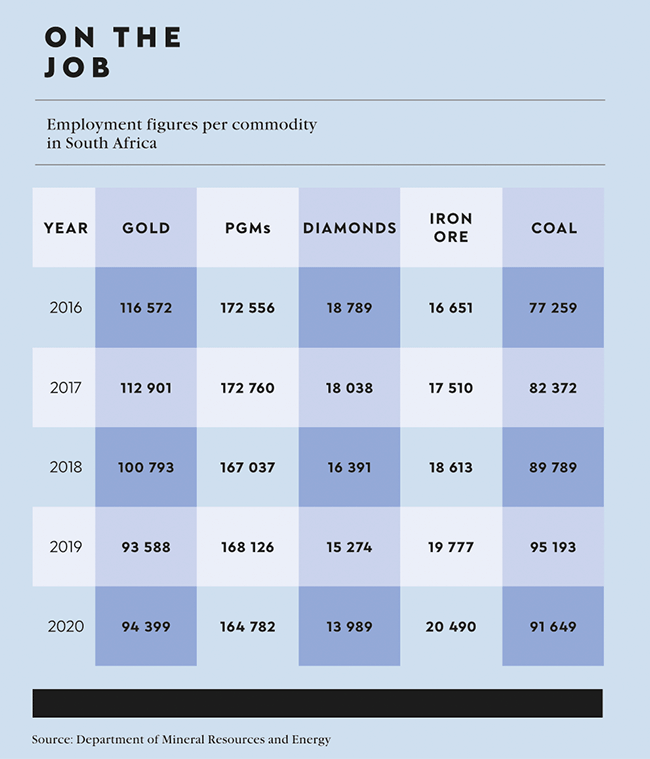

South Africa, the continent’s most established mining jurisdiction, may lose out again if a new commodities super-cycle does consolidate. While the country’s miners thrived on red-hot minerals prices in 2021, with a production rebound of 11.2% and total minerals sales 39.1% higher, the general trend in the jurisdiction has been downwards. Despite the recovery, output dropped at an average rate of 0.3% per year between 2016 and 2021.

In fact, capex into South African mining has been falling for a number of years. In 2021, gross fixed capital formation in mining in South Africa stood at ZAR114 billion. ‘That’s scary; it’s not even keeping pace with deterioration and wear and tear,’ says Minerals Council South Africa chief economist Henk Langenhoven. South Africa’s big problem is an absence of greenfields investment, which in turn reflects low investment in exploration, now down to a quarter of what it was in 1994. At the heart of the issue is the performance of the public authorities, which were sitting on a backlog of 5 326 mining permit applications in 2021.

If a super-cycle is indeed taking off – with legs that go beyond a rebound from COVID and temporary tightness in supply resulting from the Ukrainian invasion – it will be driven by decarbonisation. The big question is whether the substitution of low-carbon solutions, especially in automotive and energy generation, can indeed provide the scale of impetus that China’s expansion did in the first decade of the current millennium.

If it does, African development could be lucky enough to get another big boost.