The numbers can be deceiving when it comes to women in mining. They are disappointing, because female participation in the sector has shrunk in South Africa despite all efforts for gender equity. But as is often the case, the statistics don’t tell the whole story.

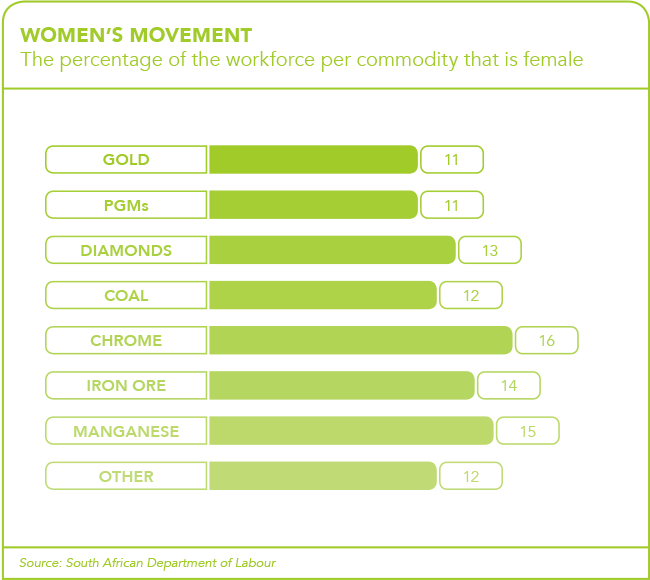

‘If we look at the current figures, women in mining make up about 12% of the country’s mining labour force. The figures did increase to about 14% around five years ago, but we are now in the same place as 10 years ago,’ says Noleen Pauls, principal geoscientist for Europe, Middle East and Africa at Reflex, a global supplier of advanced underground intelligence solutions. She is also a founding member, patron and past chairperson of Women in Mining South Africa (WiMSA), a non-profit advocacy organisation that promotes female participation in the industry through mentorship, training and networking. ‘I do think, though, that it’s easier for women to join, and be accepted into, the mining industry than it was when we formed WiMSA in 2010,’ adds Pauls. ‘There are more initiatives within the mining groups to attract and retain women, and to assist them in making the job easier. And there is more open dialogue about gender diversity.’

According to the Minerals Council South Africa (MCSA), the sector employed in excess of 53 100 women in 2017 – up from a very low base of 11 400 in 2002 but then down again after reaching 58 000 in 2015. At present, 14.9% of the country’s female mining employees work in top management, 15.9% in senior management and 18% each in ‘professionally qualified/middle management’ and ‘skilled technical professions’. Although the industry, particularly gold and platinum, is down-scaling and restructuring, the large players have underlined their commitment to recruiting women into bursary and training programmes, and to improving career prospects as well as working conditions for female employees.

The MCSA says its members are taking physical safety ‘very seriously’, in response to allegations of harassment against women miners. Its 2018 factsheet on women in mining states: ‘Changes that have been made to enable women to feel safe when working underground include improving lighting in working and travelling areas; providing safe toilet, shower and changing facilities; and (in some mines) ensuring that women have work buddies who make sure they do not have to move around quiet areas on their own.’

Companies such as Exxaro are also running self-defence courses for female staff and securing the underground women’s toilets with access codes. Exxaro is also upgrading female workers’ lamps to include panic buttons. In December 2018, the firm announced it had redesigned its personal protective equipment (PPE) clothing to make it more accommodating for women. Underground equipment, such as clothing, boots and tools, is traditionally designed for males and it tends to be ill-fitting for the female physique. Exxaro says it piloted three types of PPE uniform designs on-site, asking female miners for feedback before rolling out the uniform throughout its mines. In addition to improving physical comfort and workplace safety, there’s the challenge of not only attracting young women to this historically male-dominated industry but developing, promoting and then retaining them. ‘A survey done by WiMSA in 2016 showed that by age 55, 40% of the respondents have left the mining industry to pursue other ventures, leaving a gap in senior management and board level,’ says Pauls.

As a result, many women who enter core mining jobs as operators, and technical mining positions as geologists, chemical engineers and mechanical engineers, don’t progress beyond mid-management. While the Mining Charter has been a useful tool for gender inclusivity, it has simultaneously encouraged a numbers game that, ironically, isn’t helping transformation. Some companies are so focused on complying with gender quotas that they neglect to instil a genuine culture of diversity in their organisation and boardroom. Which in turn has been proven, again and again, to boost the bottom line and contribute to corporate sustainability. ‘Recognising and embracing the new generation of female executives in the industry will be a challenge for the traditional South African mining industry in the next two to five years. There is an abundance of female talent ready and able to take over and lead the industry to new heights,’ according to Thabile Makgala, Impala Platinum mining executive, who recently took over as WiMSA chairperson. ‘Even though it’s 2019 and much progress has been made, networking with colleagues, superiors and individuals from other organisations is something women have to do more of if we want to attempt to level the playing field and achieve our professional goals,’ she says.

Makgala speaks from experience: she was the first female learner official at a South African deep-level gold mine (Gold Fields’ Kloof and Driefontein) and later the company’s first female regional country head of technical services. In November 2018, she was named one of 16 South Africans to feature among ‘100 Global Inspirational Women in Mining’ from 28 countries. The list – now in its third edition since its launch in 2013 – was compiled by Women in Mining (WIM) with the goal ‘to attract and retain female talent in the mining industry by showcasing inspirational stories of women who have successfully pursued a career in mining’. The launch of the 2018 publication saw another South African role model – Daphne Mashile Nkosi, the founder of Kalagadi Manganese and a 2015 nominee – as guest speaker. Her struggle from rural poverty to manganese tycoon is one of the most inspirational stories in the business.

Successful female role models and mentors who understand the industry are crucial for women working in mining, because according to Pauls: ‘They provide life-long advice and a personal cheerleader, and help the mentee to push boundaries and learn new skills that she may need in future roles.’ She adds: ‘As most mentors are eager to see their mentees succeed, they help make connections. Networking also helps with making connections, which I also think is very important in directing career paths.’ That’s why WiMSA offers, in addition to networking events, its so-called ‘Mentor’s Manors’ platform whose format ranges from ‘dragon’s den’-style events to guest lectures and group discussions. ‘Our mentoring tends to focus on confidence, self-leadership, speaking up for oneself, and other softer skills that help to pave the way within careers,’ says Makgala.

The large mining companies have already introduced a multi-pronged approach to gender inclusivity. De Beers, for example, has doubled its female appointment rate into senior positions over 12 months, with 51% of new senior hires being women. In a three-year partnership with UN Women, the group is investing US$3 million to advance girls and women in its diamond-producing countries. This includes more than 1 200 female micro-entrepreneurs in South Africa, Botswana and Namibia. In December 2018, De Beers further announced the facilitation of a five-year contract for a women-owned SME from Musina, called Chibadura Trading, as the local distributor for light-duty vehicle tyres, rims and batteries for its Venetia diamond mine.

Another diamond producer, Petra, offers a leadership development programme to advance women into managerial positions, runs diversity management training sessions and ensures gender balance in new recruits: in 2018, 44% of Petra interns were female, as well as 33% of engineering learnerships, 40% of mining learnerships and 39% of bursars.

Meanwhile, Nombasa Tsengwa, Exxaro head of coal, says: ‘We have a whole lot of retainer interventions; the most impactful one that Exxaro applies is to identify a clear career path for each individual and those who are best performers are fast-tracked through independent development plans. We are also very deliberate about targeting and specifying positions that must be filled by women. If none [are placed] internally, we go externally.’

Tsengwa, who was voted ‘SADC’s Most Influential Woman in Business and Government’ in the mining category, adds: ‘Above all, women have a voice in our organisation. I am an example of the success of this approach. We are not perfect; we grow all the time and are open to suggestions.’ Anglo American has followed suggestions and invested in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) education of girls, which is vital for most mining careers. New science laboratories at Parktown High School have pushed the take-up of science as a subject choice among female grade 9 learners by 30%.

Makgala notes that high school career days and mine visits to educate girls about career opportunities in the mining sector should also be encouraged. There are many reasons for attracting young female talent – beyond increasing gender statistics – as women could make a meaningful contribution to the industry, if given the chance.