Not too long ago, artisanal mining was the only game in town. Apart from one or two exceptional sites, such as the infamous Potosí mine that funded the Spanish empire, historically mining comprised small-scale operations with a few men, intense manual labour and rapid swings from boom to bust. During the gold rush days of the last century, this kind of mining made California the wealthiest state in the US. In Africa, small-scale mining helped increase the population of Johannesburg from a few hundred to more than 100 000 people in less than a decade, following the discovery of gold in the 1880s.

Over the last 80 years, however, the bulk of mineral production and revenue generation has shifted to large-scale operations, holding exclusive access to particular areas and deploying technologies that lie beyond the expertise or budget of most smaller operators. Under these conditions, artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) has often been seen as a problem to be solved, even though it continues to employ more people than conventional, large-scale mining.

Things, however, are changing. Economic conditions continue to attract thousands of people to the artisanal sector and a new generation of affordable equipment is putting improved yields within their reach. Governments are recognising that well-regulated ASM may offer a way of broadening the economic base of mineral-rich districts, and several established companies are finding new ways to work with small-scale miners.

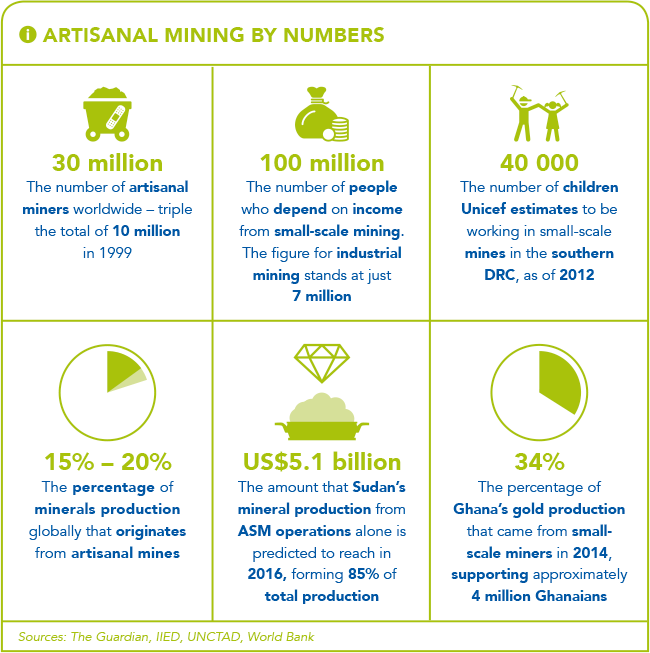

An accommodation is clearly needed. According to the World Bank, since 1999 the number of small-scale miners has increased from 10 million to 30 million people, while around 100 million people depend on artisanal mining as a source of income, compared to about 7 million people in industrial mining. It has also been estimated that 15% to 20% of total global minerals production comes from the small-scale sector.

This type of mining brings a particular set of problems that will have to be addressed before it can realise its potential. The hard-to-supervise nature of ASM means that its environmental impacts are often very high compared to production, with particular concerns being raised about erosion and serious pollution through the massive use of mercury in artisanal gold production.

In some African states, small-scale mining has been linked to the widespread use of child labour; losses in food production as local agriculture declines; and funding for organised crime or paramilitary groups. It has been extremely hard for states to generate consistent revenues from the sector to support national development, and many are concerned that small-scale techniques are an inefficient way of extracting a finite mineral resource.

However, if ASM can be effectively regulated, there are many potential benefits. As analysts at the Economist have noted, artisanal mining creates jobs in some of the most remote parts of the continent and tends to sustain these jobs more effectively than larger producers during boom and bust cycles. Small-scale miners’ immediate earnings are generally spent locally, with their savings invested in other local businesses. They are also prepared to mine marginal deposits that would simply not be considered by any larger operator.

For established mining companies, fair and effective engagement with small-scale miners is important not only because of these potential benefits but also because it helps them maintain legitimacy among host communities that might otherwise be excluded from a mine’s local opportunities. Events earlier this year – when a number of artisanal miners were killed by state security forces at the massive Kibali gold mine in the DRC – were indicative of the serious tensions that can arise when governments and the formal sector fail to broker an effective compromise.

At an international level, there is increasing co-ordination of efforts to improve the regulation and integration of small-scale mining in Africa. Until recently, the World Bank operated its Communities and Small-Scale Mining programme, the intention of which was to prompt governments to begin regulating and encouraging the sector. Now that this has concluded, it operates numerous bilateral ASM partnerships with African states.

Meanwhile, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development has initiated a similar multi-state project that is aimed at developing stable supply chains to link artisanal African gold producers with buyers outside the continent.

Developments are evident in many parts of Africa. Earlier this year in Ghana, for example, the state and business leaders began discussions towards comprehensive reform of the ASM sector, which has been partly regulated for some time already.

‘What we need is a major shift from an ASM sector driven by poverty and a lack of options to ASM operations that are run like efficient businesses with adequate access to finance,’ Toni Aubynn, CEO of the Minerals Commission, said at a symposium organised by the UK-based International Institute for Environment and Development. ‘We need to shift from an insecure and dangerous sector to one that enjoys secure rights and provides safe and decent jobs.’

Similar developments have been taking place in Mali since 2014, where attempts are being made to formalise the sector along the lines of conventional mining. As Abdoulaye Pona, president of the country’s Chamber of Mines, said in comments to Reuters: ‘Miners will no longer continue to dig holes from right to left, here and there. Mining will be done in selected corridors, and at the end of the activities we will close the holes to restore the ecosystem.’

Other nations have the same idea. Sudan has recently started looking for ways to formalise the sector, in a country where 85% of total minerals production (valued at an estimated US$2.5 billion) comes from artisanal activities. And in South Africa, civil society groups and the Human Rights Commission are pressing for increased recognition of legitimate ASM activity, distinct from the ‘illegal’ mining of disused gold workings that has drawn a lot of media attention.

Across the continent, the relationship between small-scale miners and larger firms will be critical to whichever policies are chosen. Despite the history of antagonism here, as both groups compete for the same underlying resources, some established companies are taking the lead in finding new ways to work with the ASM sector.

Across the continent, the relationship between small-scale miners and larger firms will be critical to whichever policies are chosen

At Randgold Resources’ operations in Mali, the company has reached an agreement to allow artisanal mining to proceed on shallower gold deposits in its lease area. ‘People have been doing this for hundreds of years. We respect that. But when they apply for a government permit, the government deems it illegal,’ said the company’s community development manager, Hilaire Diarra, in a recent discussion with Mining Weekly. ‘When we offer an alternative, they’ll jump at it. We’ve rolled this out to other operations in the DRC.’

A similar approach has been adopted by AngloGold Ashanti at its Siguiri gold mine in Guinea – a region where artisanal mining has been part of the economy for centuries. On the other side of the continent, in Tanzania, the World Bank has been helping broker a long-running and extensive collaboration between mining houses and ASMs. Here AngloGold works in conjunction with the Geita Region Miners Association, representing artisanal miners. The company provides its technical personnel as trainers to local small-scale operations, covering aspects of efficient mining, including geology, metallurgy and occupational health.

In addition to government and corporate activity, there has been a proliferation of third-sector organisations that are focused on integrating Africa’s small-scale mining into more formal networks of production and sale. Bodies such as the Artisanal Gold Council aim to improve the technological capabilities of ASM gold miners by providing access to direct smelting methods, with a view to eliminating the use of mercury as a separating agent.

Further down the value chain, Fairtrade Gold is establishing a certification scheme that links artisanal producers with buyers, and ensures operations are free from labour exploitation and/or environmental mismanagement. The Diamond Development Initiative International (partly funded by jewellers Tiffany & Co) is taking a comparable approach to Africa’s ASM diamond production.

Ultimately though, there is still insufficient co-operation, sharing of resources and regulation of ASM activity in most African states. For its benefits to be realised, there needs to be further oversight and formalisation – otherwise the risk is that the lion’s share of revenues will disappear into the pockets of middlemen, or be lost in inefficient and risky methods of production. If a clear understanding of roles can be negotiated between small-and large-scale miners, then there is every possibility that artisanal mining will become an increasingly central part of the continent’s mining environment.