As prices have fallen over the past years, analysts have argued that African states didn’t realise the full potential of the last mineral commodities ‘super-cycle’. Iron ore projects have stalled across the continent, platinum producers have laid off thousands of staff and there’s been a retreat of investment from gold exploration – although the gold tide may be turning in light of global economic instability.

Some expected gains never materialised for mining companies, nor their host communities or countries, and it may be some time before a rise in prices makes marginal projects viable again. But other processes, set in motion during the boom years, have continued – notably the reform of mining tax regulations across the continent.

At the height of the past super-cycle, when mineral prices were good, states across the world took stock of their mineral taxes.

Governments often concluded that existing tax regimes were failing to generate adequate revenues from their finite mineral endowments, and passed various laws to increase the share of profits that went to host countries. This was the much-discussed era of ‘resource nationalism’ that continues into the present.

While prices have fallen, a global consensus regarding the need for mineral tax reforms has persisted. This is particularly true across Africa, where the tax taken from mining has historically been much lower than in North America or Europe – a result of the high-risk nature of investment in some places, and of ‘sweetheart’ legacy tax deals made decades ago.

In some areas there is evidently a need for reform, particularly to simplify tax collection and eliminate lost revenues through transfer pricing. Even in South Africa, with its historically well-developed relationship between the state and mining sector, it’s been argued that the country lost US$620 million in untaxed mineral export earnings between 2002 and 2005 through trade with the US alone. But recognising the need for reform and implementing reform successfully are two entirely separate things.

Many companies accept the need to improve local taxation regimes but there is concern that, under current conditions, the wrong approach may limit their ability to operate predictably – or even at all.

Hany Besada and Philip Martin, analysts at the North-South Institute, propose that African states are now drafting the ‘fourth generation’ of their mining codes. Almost two-thirds of African governments rewrote their mineral tax laws between 1990 and 2000 (when the focus was on market liberalisation) to attract investment.

In the fourth generation, according to Besada and Martin, states are principally seeking ‘to integrate mining into Africa’s long-term development at the local, national and regional levels. Above all, this means transforming natural resource capital and transient wealth into lasting forms of capital and industrial growth, with the ultimate objective of reducing African states’ economic dependence on primary resource exports’.

While this is the broad goal of the AU’s 2009 Africa Mining Vision, the evolution of tax regimes and broader mining codes has varied greatly between states.

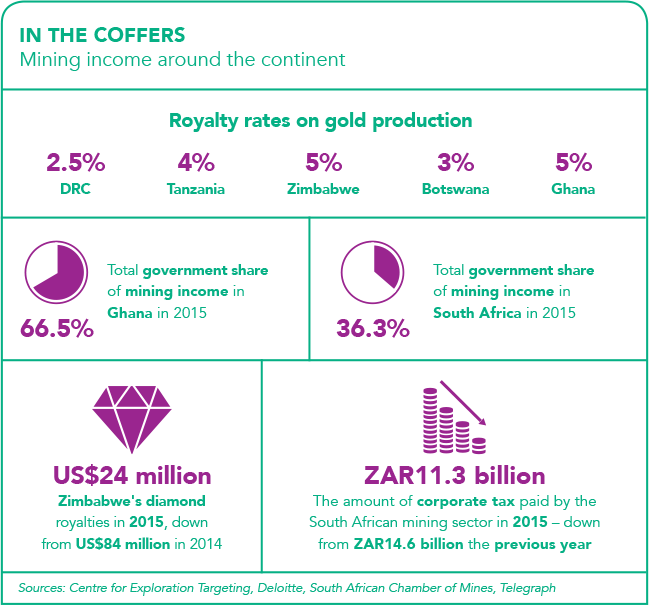

In Zimbabwe, for example, the government has taken a steadily increasing direct stake in mining operations – it has a 50% share in all diamond production, for example, and this year it announced plans to increase this to 100%. But Zimbabwe has been unable to realise increasing tax and royalty revenues from this approach. Diamond royalties in 2015 were US$24 million, according to analysis by the UK’s Telegraph, down from US$84 million in 2014.

In Tanzania, the state may also be facing difficulties, after changes to its overall tax system were announced in 2016. Reuters reports that a number of the country’s largest foreign investors, including its mining firms, are planning to scale back investment after the new regime was announced – at the same time as the government reached a substantial settlement with its largest gold mining companies, regarding unpaid corporate taxes.

In Zambia, the challenges of mineral tax reform are evident in the country’s rapid shift between different models.

In late 2014, the government announced that it would cease collecting income taxes from mines, and would instead seek revenues through an increased royalty rate – which rose from 6% to 20%.

and gemstone mining workforce being regulated

By April 2015, however, the decision was reversed in the face of wholesale opposition from mining firms that argued falling copper prices meant it would lead to job losses and production cuts. Zambia’s revised mineral tax regime now comprises income tax at 30%, a royalty rate of 9% and variable profits tax at 15%.

Other African countries are focused on reforms in the artisanal and small-scale mining sector. Artisanal mining has proven difficult to tax effectively, but it has drawn increased attention following the downturn in prices – production and income in the sector have to some extent been maintained, while falling at larger operations.

In Madagascar, the government has suggested that it plans to integrate informal gold and gemstone miners – one of the largest sectoral workforces in the country – into the tax and environmental regulation systems.

Against this general backdrop of tax reform, South Africa is arguably receiving the most investor attention at present.

In what is the continent’s biggest minerals economy, concerns have been raised following the unanticipated April 2016 announcement of the new Mining Charter, to be implemented in early 2017. As well as changes in mining ownership laws, the revised charter includes new taxes earmarked for skills and local supplier development – including a 1% levy on the revenue of foreign suppliers, tax of 0.15% for research, and a defined revenue contribution to community development.

The focus on taxing turnover, rather than profits, has generated concern and criticism from industry representatives faced with falling margins. South African Chamber of Mines CEO Roger Baxter argues that ‘the cumulative effect of the proposals, combined with existing corporate taxes and royalties, skills development levies and more, would materially affect the viability of an industry already in crisis’.

These concerns are shared by numerous observers who consider uncertainty regarding future net income as the central factor limiting investment – and growth in tax receipts – in South African mining.

Analysts at Deloitte report that ‘while the reviewed charter has brought some clarity in areas of prior uncertainty, there is an overall feeling that underlying uncertainty persists. The investment required as the industry moves out of the down-cycle may define the speed at which it returns to a growth path. South Africa cannot afford to again fail to take advantage of the next up-cycle, and investor confidence in the regulatory and policy landscape is critical’.

The decision to revise the charter follows the report of the government’s own Davis Tax Committee, which warned in 2014 about risks regarding the earmarking of mining revenues to address external problems, saying that ‘changes to tax design should be approached cautiously, without trying to compensate for problems that lie outside the tax system’.

The South African situation is representative of the difficulties elsewhere on the continent. African governments, seeking to generate maximum minerals income, are in contest with international investors wary of further exposure to local uncertainty after a minerals boom when it briefly looked like both sides could get what they wanted.

It’s not necessarily the case that higher taxes inevitably deter investment, or that lower taxes inevitably bring more. As research by Australia’s Centre for Exploration Targeting has shown, it’s the overall perception of policy that matters, rather than the specific rate.

South Africa had one of the lowest effective mining tax rates in Africa in 2015 at a total government share of 36.3%, but it did worse in terms of policy perception (relative to tax rate) than Ghana, where mineral taxes give a government share of 66.5%.

If mining tax reforms generate revenues that only benefit a small group; ultimately reduce total employment; or deter investment entirely, then change may be worse for host countries than no reform at all. But improved tax regimes that deliver a larger share of mining income to host countries can demonstrably co-exist with a thriving mining sector.

The minerals are not going anywhere, and there are companies willing to accept reduced margins for long-term security. In South Africa, other factors – including global commodity prices as well as the uncertain policy environment – have contributed to an ongoing period of relative stagnation.