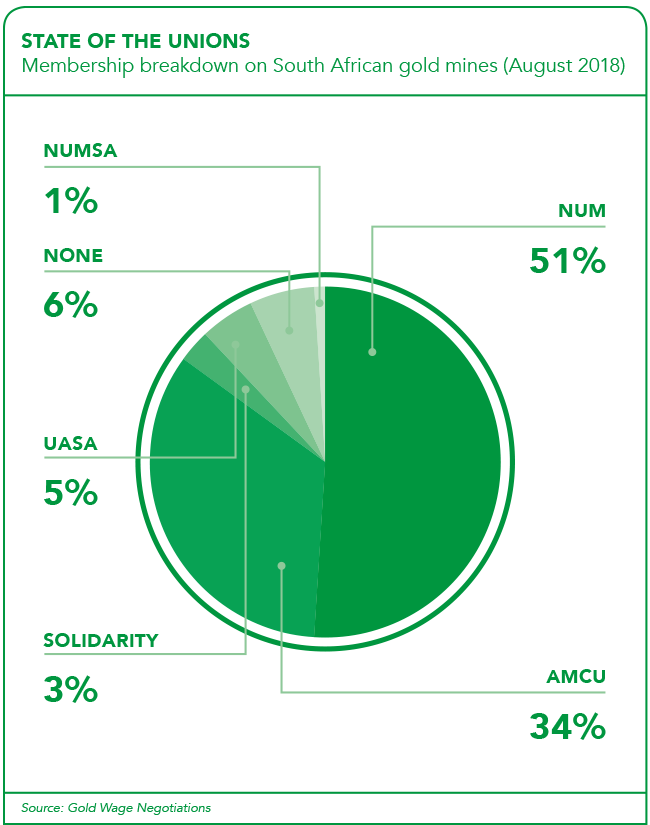

Trade unions and mining houses in South Africa are again locked in what looks like could be another protracted wage-negotiation process – this time in the platinum sector, following industrial action last year in the gold sector that saw frequent outbreaks of violence, including several deaths. However, the legal framework that governs South Africa’s industrial action is slowly catching up, as legislators attempt to rewrite the statute books to minimise factors that typically increase the likelihood of violence and intimidation during strikes.

Anastasia Vatalidis, head of labour and employment at Werksmans, says that in the historic judgement in March in the Labour Court (LC) on secondary strike action, the LC ruled (after deliberating for two weeks) that the right to engage in secondary strike action was not unfettered. In the matter of Anglo Gold Ashanti and Others vs the Association for Mineworkers and Construction Union (Amcu), the court held that before employees may engage in strike action, certain procedural requirements of the Labour Relations Act (LRA) and the reasonableness requirement must be met in order for the secondary strike to be protected.

‘Essentially, it’s an enquiry into the extent of pressure that is placed on the primary employer, in this case Sibanye-Stillwater,’ according to Vatalidis. The judgement came after Amcu went on strike at Sibanye-Stillwater’s gold mines, followed some months later with notices of intention to commence secondary strikes across the gold, platinum, chrome and vanadium sectors at numerous further employers, including Impala Platinum, Rustenburg Platinum, Northam Platinum and Harmony Gold. Vatalidis says that the court concluded that this did not accord with Section 66(2) of the LRA and ruled that the proportionality assessment didn’t permit the grouping together of a collection of secondary employers in a specific industry.

Melanie Hart, partner at Fasken, concurs, adding that what was unusual about Amcu’s proposed campaign of secondary strike action in support of the primary strike at Sibanye-Stillwater, was that the union attempted to pool together 15 employers with operations in different commodities, in order to increase pressure on the primary employer to accede to their demands.

‘Had the court ruled in Amcu’s favour, this would have paved the way for Amcu to use a similar strategy, relying on the combined socio-economic impact of the secondary strikes on the primary employer, during the current wage negotiations in the platinum sector. However, the court found that the companies served with the secondary strike notices stood to suffer considerable losses as a consequence of the secondary strike, in circumstances where it would have no impact on Sibanye-Stillwater. As such, the secondary strike was disproportionate to the goal of the strike and therefore not protected. Amcu has since petitioned for leave to appeal.’

Turning to the platinum sector, where Amcu recently called for 48% wage increases in some instances, Hart argues that this will ‘absolutely’ set employers and the union poles apart, and lead to another round of protracted negotiations similar to recent events in the gold sector. ‘Considering the huge chasm this way-above inflation demand is likely to cause between the parties, the likelihood of protracted strikes later in the year is very real,’ she says.

Fiona Leppan, director: employment at Cliffe Decker Hofmeyr, says the heart of a primary strike, being a power play between an employer and its employees, is absent in a secondary strike, as a secondary employer cannot put an end to a secondary strike by complying with a demand, as the secondary employer would be party to the primary employer’s dispute with its workforce.

‘The LC found that the factual enquiry under the LRA does not permit such a “grouping together” when applying the proportionality test, because it ignores the critical issue that an assessment of the impact of the secondary strike calls for a consideration of all the relevant facts and a weighing up of relevant factors that may be unique to a secondary employer.’

Leppan says that lumping employers together for that purpose deprives the single secondary employer of the protection afforded to it under the LRA – in essence, not to have to endure a secondary strike that is unreasonable in relation to its impact. The current wage negotiations in the platinum sector are taking place against a contraction of 1.5% year-on-year in overall mining production in May. This extended the sector’s fall to a seventh consecutive month, according to Statistics South Africa.

Henry Ngcobo, employment law director at Bowmans, says if prolonged strikes happen this year in the platinum sector, it ‘certainly’ could impact negatively on employers’ operations and increase the risk of them being unable to honour their contractual obligations as suppliers of platinum to international and local customers.

‘They may then have to declare force majeure if the contingency measures they have put in place to mitigate the impact of the strike turn out to be insufficient or inadequate.’ He adds that miners sometimes have stockpiles of reserve supplies and use skeleton staff in an effort to counteract the impact of a strike but, again, it would depend entirely on the duration of the strike.

In South Africa, skeleton staff are sometimes intimidated by striking workers and often strikes are characterised by violence. It boils down to a power play between employer and union members – each side tries to exert the most pressure on the other to achieve its objectives.

In March this year, says Ngcobo, ‘coal producer Wescoal issued notice of force majeure to Eskom of its inability to continue supplying coal from its mine at Vanggatfontein after the dismissal of its employees following a violent strike. It’s common for commercial contracts to include industrial action or strike action as a defined force majeure event, especially in South Africa, where long and violent industrial action is a common occurrence’.

He goes on to explain that impossibility of performance does not excuse the performance of contract, and a defaulting party has to show that the force majeure provision is reasonable and fair in all circumstances. The defaulting party may even be required to demonstrate that it has taken all reasonable steps to avoid the occurrence of the force majeure event and to mitigate its effects on the aggrieved party. In the context of strikes and industrial action, this is more so.

If the defaulting party can demonstrate that it did all it reasonably could to avoid the disruption; that the performance is objectively impossible; and that it was unavoidable by a reasonable person, the courts are likely to uphold the defence of force majeure.

Ngcobo says that the risk of an employer having to declare force majeure on a contract is primarily dependent on the nature of the strike demands; the nature and intensity of the strike itself; the duration of the strike; and the planning and effectiveness of any contingency measures employers have put in place to minimise the impact of a strike on their business operations. ‘Management’s objective should be to minimise the disruption caused by strike action and to return to full production as soon as possible,’ he says.

Warren Beech, partner and head of mining and infrastructure at Eversheds Sutherlands, argues that the South African labour relations legal framework that governs industrial action is catching up with that of countries such as Australia and Canada, where strikes tend to be less violent.

‘These countries have strong legal frameworks that have been in place for a long time,’ he says. ‘In South Africa, the Labour Relations Amendment Act [LRAA], which came into effect in January this year, is an attempt to facilitate an environment and framework that reduces the levels of violence that occur by requiring, among others, a secret strike ballot, rules regarding picketing and advisory arbitration in certain circumstances. Around the world where mining takes place – including countries in South America and in many African states – strikes are always a very emotive issue and often involve employees from, and other members of, impoverished local communities around the mines who want to participate in the mineral wealth. Often, the lines get blurred and strikes get violent.’

Beech adds that the fact strikes in countries such as China – another significant commodity producer – are not particularly violent is not so much a result of a strong legal framework as much as it is a function of that government exerting control over its population. However, he says, South African laws are getting closer to those of Australia and Canada, and so he expects to see ‘a greater degree of level-headedness coming from our unions and employers in time’.

Vatalitis agrees that while the amendment was introduced to address strike violence in circumstances where employees who do not want to participate in strike action are often subject to intimidation and harm, whether the courts will actually enforce the amendment that requires trade unions and employer organisations to provide that a ballot be recorded and in secret will only be tested in time.

‘To date our courts have not been willing to declare a strike unprotected merely as a result of a union having failed to hold a ballot, let alone a secret ballot.’