Artisanal or small-scale mining (ASM) is by far the oldest form of mineral extraction, and still the most extensive in terms of the number of people it employs worldwide. From prehistory – when simple commodities such as chert, salt and ochre, were mined by small communities – through the age of bronze and iron smelting and into the present, artisanal miners have been ex-tracting minerals from the ground.

Many of the world’s oldest artisanal mines are in Africa – notably the Bomvu Ridge iron ore mine in Swaziland, where mining was under way more than 40 000 years ago.

However, although small-scale mining has a long history, it became increasingly marginalised worldwide, with the rise of joint stock companies and industrialised mineral extraction. In fact, it’s been argued that the first-ever stock trade related to shares in a mining venture, in 1288.

By the early 20th century, the days of the mass gold rush and similar small-scale booms were largely over. By 1910, during the Porcupine Gold Rush in Canada – which would see more total ounces mined than any other gold discovery, at 67 million oz to date – small-scale miners were more or less completely excluded in favour of larger companies.

There’s a clear sense that artisanal mining is the ‘original’ form of mining, and it has certainly remained the most widely practised across the continent and around the globe.

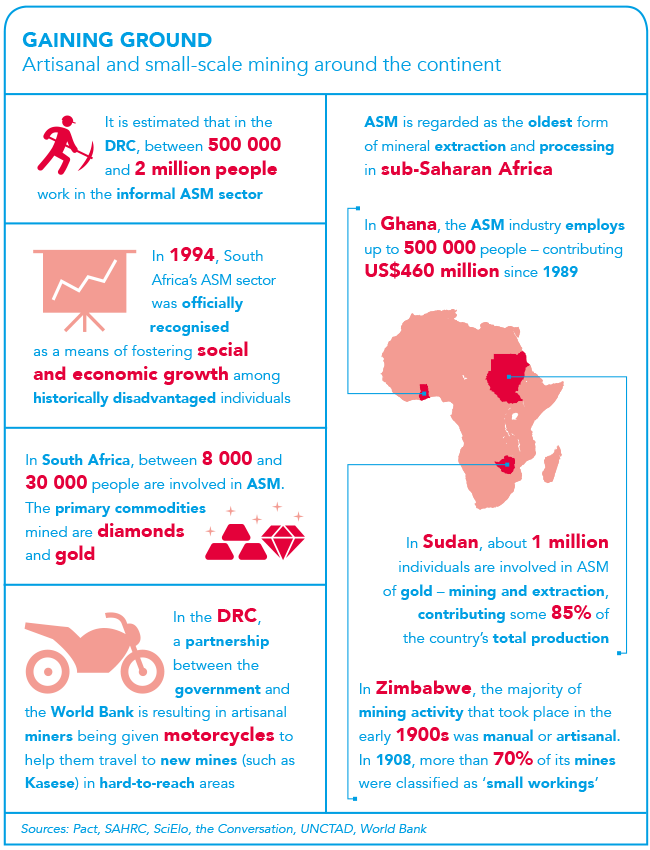

According to the World Bank, there are around 20 million to 30 million artisanal miners worldwide, working in more than 80 countries, and accounting for more than 20% of global gold production (among other minerals). More than 100 million people depend on small-scale mines for their basic economic support.

In countries such as the DRC, the International Finance Corporation estimates that there are more than 2 million small-scale miners, producing around 90% of the country’s total minerals production, a great deal of which is exported through informal networks. In Sudan, the UN Conference on Trade and Development has similarly estimated that there are more than 1 million artisanal gold miners, supporting around 4 million people and responsible for more than 85% of the country’s total gold production.

Artisanal mining never went away, but it’s only relatively recently (in the last 30 years or so) that it has become a focus of government policy and a subject of much debate within the mining sector. Large-scale industrial mining has, for decades, been seen by African governments as the most efficient way of extracting minerals – both in terms of the specific techniques for processing and smelting ores, and in the sense that a small number of big companies are easier to regulate and tax than thousands of small-scale producers.

However, shifting global metals prices, new transport links and flows of information enabled by the internet mean that Africa’s small-scale miners have found increasingly efficient connections to world minerals markets, through networks of middlemen who sometimes operate on the edge of legality. This has steadily increased competition between large companies and artisanal outfits, leading in some cases to direct conflict.

Faced with this scenario, governments and large companies have looked for ways to broker a truce. There has been an increasing recognition that small-scale mining can be of national value – as a means of broad-based employment and local spending, and as a potential source of tax revenues.

Artisanal mining also offers a way for countries to exploit mineral deposits that had been deemed ‘uneconomical’ by larger firms, usually because the deposit was too small, too complex, or too uneven a grade to mine via conventional methods.

There are two main issues to be resolved. Firstly, whether large companies and artisanal producers can co-exist within the same mineral areas, with even-handed regulation of resource rights, permitting and environmental monitoring. And secondly, whether African governments can find a reliable way of monitoring production and financial flows among small-scale producers, so as to equitably incorporate them into the national tax base. In the first case, some larger companies across the continent have developed their own approaches to working with small-scale miners, as a way of defusing tension or ensuring that all local mining participants can share in a particular deposit. In other cases, incorporation of small-scale mining activity has taken the form of national initiatives that attempt to integrate small-scale miners into the overall tax and regulatory network.

In both instances, developments in Ghana make a useful case study. In terms of initiatives from the private sector, many analysts have pointed to the example of Gold Fields.

In 2012, the mining company conducted a baseline social study of small-scale mining around its massive Tarkwa and Damang mines, engaging directly with artisanal miners and their host communities to formulate a long-term ASM strategy. This gave small-scale operators access to part of the mining areas, and helped bolster the company’s long-term social licence to operate.

The government of Ghana has also been considered notably proactive in its engagements with the small-scale sector, relative to many other African states. Successive Ghanaian governments have introduced legislation aimed at formalising aspects of artisanal activity, and integration of the industrial and ASM sectors is a consistent policy goal. But, as analysts at the Oxford Business Group note, the government body responsible for purchasing Ghana’s small-scale gold production has reported that, annually, the state loses around US$139 million in missed taxes and royalties. Recent attempts to impose a 10% tax on ASM producers and on the middlemen who purchase unprocessed minerals have met with fierce resistance from the Ghana National Association of Small Scale Miners.

Many analysts now argue that providing security of tenure – some kind of formal mining right – to artisanal miners may be critical for ensuring their participation in other aspects of regulation. A recent integrated study of small-scale mining in Africa, led by Mark Wilson from the University of Michigan, argues that ‘sustainable ASGM [gold mining] development will not be easy without support for miners to legalise and formalise their activities. The costs of permit fees, of travel expenses and of work time lost contribute to their calculations of the perceived value of actually obtaining mineral tenure rights’.

The study concludes that these cost constraints for small-scale miners ‘make the transferability of mining rights fundamental to miners investing in sustainable and environmentally sound activities. Mineral tenure can be used, for example, as collateral for financing aimed at developing and sustaining improved mining’.

In other words, it may yet require a substantial overhaul of the mining cadastral and permitting systems in many African states in order to give small-scale producers a measure of security that would allow them to access financing, make investments in improving their mining practices and, ultimately, contribute as taxpayers.

Another African country that is often hailed as a success in this regard is Tanzania, where an estimated 1 million people work on artisanal projects. The Tanzanian government and the World Bank have collaborated on ASM policy for a number of years. The country’s Mining Act of 2010 established mineral rights for small-scale producers, and the state has at times adjudicated in favour of ASM producers. An example is its tax dispute with Pangea Minerals, which saw one of the company’s mining blocks re-awarded to several thousand small-scale producers.

However, it remains to be seen whether the right balance can be struck, to maintain the presence of larger companies while expanding support for the ASM sector. Tanzania has at least partially succeeded in the integration of artisanal producers into the national tax base, and in creating a regime where the legal and operational parameters for each subsector are relatively well understood. The World Bank has also set aside a specific fund that offers grants aimed at boosting revenue collection in Tanzania’s ASM sector.

At present, there are one or two relatively well-advanced test cases among the many African states that host small-scale mining. Larger mining firms, ASM representative groups and other countries are watching to see what happens in Ghana and Tanzania, as well as a handful of other countries that have developed their ASM policies. But vast funds continue to flow out of the continent’s ASM sector through informal networks, with relatively little tax value returned for national development and, often, neither large nor small companies can depend on tenure awards.

In many African countries, there remains a relatively high potential for conflict between industrialised miners and artisanal outfits, a situation that will surely persist until a coherent policy solution can be found.