The global copper market has been in supply deficit for the past three years, with the United States Geological Survey estimating that demand exceeded production by 400 000 tons last year.

Tom Albanese, the former CEO of diversified mining giant Rio Tinto, anticipates that global copper use over the next 20–30 years will exceed humankind’s total historical consumption of copper over the preceding seven millennia.

Ore grades are falling and major new land-based discoveries are becoming less frequent, and not just for copper – mining companies of all varieties are looking for more profitable sources of ore.

Just as the decline of land-based crude oil reserves has driven exploration for ‘unconventional’ hydrocarbon supplies, in Canada’s tar sands or deepwater Atlantic drilling off Brazil, unparalleled demand for various mined commodities is now leading explorers towards the seabed.

Coastal and deep ocean floors are potential treasure houses of minerals, with reserves greatly exceeding those remaining on land – states and private companies are already delineating the most productive areas beneath the waves. But with its phenomenal costs, uncertain technological efficiency and a relatively undeveloped legal and environmental framework, seabed mining presents major challenges for the participation of African states and companies. As the rush to stake claims intensifies, there is a risk that some countries may lose out.

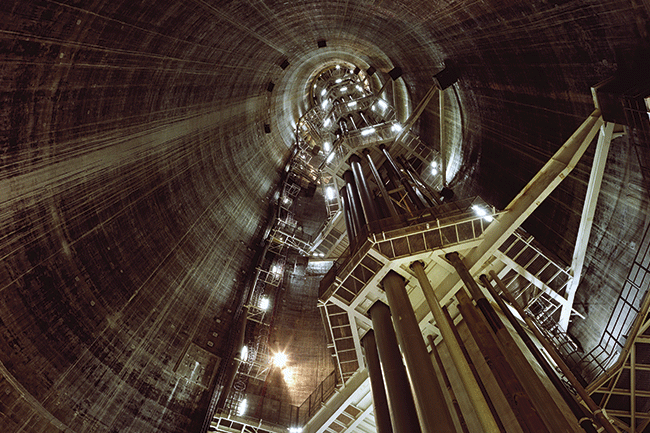

It’s been known for decades that the ocean floor holds significant mineral wealth in three general forms. There are alluvial minerals like diamonds, phosphates and iron ore, washed out from land-based deposits and laid down in sediments on the coastal seabed. There are massive sulphide deposits, often containing rich grades of copper and gold, which precipitate as rising hillocks around ‘black smoker’ volcanic vents on central ocean ridges.

There are also vast fields of potato-shaped polymetallic nodules that carpet the sea floor in areas along some fault lines – for example the 7 420 km Clipperton Fracture Zone in the central Pacific. The nodules contain a varied mixture of nickel, manganese, copper, cobalt, molybdenum and rare earth elements, requiring little drilling or blasting to harvest them.

The coastal and deep ocean floors are potential treasure houses of minerals, with reserves greatly exceeding those remaining on land

While the potential for mining the seabed has been under discussion since the middle of last century, concrete developments have only been made in the past 20 years. The International Seabed Authority (ISA) was established in 1994, drawing on principles enshrined in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, with the aim of regulating access to seabed minerals that lie beyond the jurisdiction of any coastal states.

The ISA’s oversight of seabed mining is based on the idea that deepwater minerals are part of the ‘common heritage of mankind’ and should be accessible to both coastal and landlocked states. While it has taken some time for the first permits to be issued, the ISA has now granted at least 12 licences to explore various regions of the ocean floor. These are issued either directly to states or to private companies operating under state sponsorship.

Outside Africa much recent development has occurred in Australasia, particularly around Papua New Guinea (PNG) and New Zealand. Toronto-based Nautilus Minerals has recently returned to its high grade Solwara I project, sponsored by the PNG government, where it has identified a phenomenally rich indicated resource of 1.03 million tons of ore at 7.2% copper, 23 grams per ton (g/t) silver, and 5g/t gold. By comparison, the average ore grade of land-based copper operations was estimated at 0.61% in 2009.

After concluding a funding dispute with the PNG government, which postponed development of the project, Nautilus announced it would spend US$180 million–US$260 million on a specialised mining vessel to retrieve ore at the Solwara project. The company has seen keen interest from major mining houses – Metalloinvest holds a 20.75% stake and Anglo American 6%.

There’s been similar recent activity in New Zealand where several companies have established claims to rich deposits of iron ore off the coast of the North Island. These include Ironsands Offshore Mining and Trans-Tasman Resources, which defined a significant ferrous sands resource of 4.6 billion tons ore at 6.23% iron.

Deepwater minerals are part of the ‘common heritage of mankind’ and should be accessible to both coastal and landlocked states

Elsewhere, the UK government announced a partnership with US firm Lockheed to explore for polymetallic nodules over a 58 000 km² area of the Pacific floor. The UK joins several other states that received exploration permits since 2001 – including Russia, Bulgaria, Cuba, Czech Republic, Poland, Slovakia, Korea, China, France, India, Belgium and the island states of Nauru, Tonga and Kiribati.

In Africa, the state that has seen the most activity is Namibia, where a form of seabed mining has been in operation for decades as part of the state’s partnership with De Beers.

The Debmarine Namibia joint venture operates on the extensive marine diamond deposits to the north of the Orange river mouth, with an estimated 80 million carats (Mct) located in shallow waters off the coast – around 90% of the country’s total diamond reserves. By harvesting diamond-bearing gravels from depths of 90–140m, and processing them aboard the ship, the company is able to produce around 1 Mct every year.

Namibia has also seen a great deal of interest in the potential for mining marine phosphates – the base chemicals for most fertilizers. From around US$80/t in 2007, the value of phosphates has rocketed in recent years to US$430/t in 2009 before stabilising at around US$170/t. Marine phosphate exploration in Namibia has been led by UCL Resources, with its expansive Sandpiper project located south of Walvis Bay.

Sandpiper has been estimated to hold reserves of 133 million tons at 20.4% phosphorus, with a further indicated and inferred resource of 1 688 million tons at similar grades, all at depths from 180–300m.

Elsewhere in Africa, however, there has been relatively little development of seabed mineral resources and no African states have sponsored exploration in the deep oceans beyond their territorial waters. As British Prime Minister David Cameron observed, there is now a ‘global race’ to secure exploration rights and commence mining on the sea floor.

But African states are not well prepared to capitalise on this new opportunity, for a set of related reasons. The first is cost. A study in 2008 calculated that it would cost around US$2.26 billion a year to run an operation for harvesting deep sea manganese nodules, including maintaining the undersea mining equipment, transport vessels and a specialist on-shore processing facility.

The other major constraint is technological expertise, which itself comes at a high price. Any state or company that seeks to enter this technically demanding area would need advanced knowledge of areas like sea floor geophysical survey, the deployment of remotely operated vehicles, marine ecology, and the ability to monitor and mitigate the environmental effects of mining at great depths.

The environmental dimension to seabed mining poses one of the major challenges to its future development – there is a sense in some quarters that environmental understanding of the activity has lagged behind the granting of permits and development of extractive methods.

The environmental dimension to seabed mining poses one of the major challenges to its future development

This is clear in the case of Namibia, which has just imposed an 18 month moratorium on marine phosphate mining in the country. Moves towards phosphate mining had drawn criticism from commercial fishermen, scientists and environmental groups who argued that potential disruption of marine ecosystems had not been adequately assessed. There are environmental risks from direct disturbance to the seabed as nodules are harvested or hydrothermal vents cut open, and from the treatment of tailings material. Some companies have proposed that tailings could be piped back and deposited on the ocean floor, but this might generate a sedimentary plume that affects large areas outside of the mining lease.

From an investor’s perspective this makes marine miners a riskier proposition – environmental restrictions and costs may rise significantly as society becomes more aware of this activity.

While environmental issues are big question marks hanging over seabed extraction, African states and companies also need to find a way of entering the sector in the first place.

Brazil’s former defence minister Nelson Jobim suggested it may be necessary to create regional or transatlantic agreements so that African states can partake in undersea mining. He was suggesting an agreement between Brazil and West African states.

Whether it’s through overarching bodies like the AU, or regional blocs such as the SADC or ECOWAS, financial and technological co-operation may be the only way for many countries to access these mineral reserves.