Let’s start with the worst-case scenario, before imagining the best-case ‘sunrise’ scenario, which envisions South Africa as the continent’s most transparent and efficient mining jurisdiction.

‘It is 2028 and the delays and corruption in the granting of prospecting and mining rights under the amended Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act (MPRDA) have grown worse […] with 10-year waiting periods increasingly common,’ writes Anthea Jeffery, head of policy research at the Institute of Race Relations (IRR), in her policy paper titled Sunset or Sunrise for Mining in South Africa.

‘The longer the delays continue, the more officials in the Department of Mineral Resources (DMR) can solicit “inducements” to speed up the process.

‘The MPRDA’s vague rules also make it easy for these officials to delay the granting of rights on the basis, for example, that communities have not been adequately consulted, or that the mining company’s capacity to fund post-closure environmental rehabilitation has not sufficiently been shown.’

Thankfully, this bleak ‘sunset’ outlook is made up. There’s no reason why South Africa’s prospecting and mining rights processes can’t still be improved and become more transparent, efficient and fair.

The country’s new regime has sparked cautious optimism among industry role players. Mining minister Gwede Mantashe said in his budget vote speech in May that the issuing of mining rights and the proper processing of applications for mining licences was among his department’s key priorities. He promised to weed out corruption within the DMR and highlighted other challenges, such as delays and the double-granting of licences.

‘The backlog in new mineral right applications stretches as far back as 2012 in some regional offices,’ he said. ‘It has further been found that the applications for renewal of prospecting right applications go as far back as 2010. The implication of unprocessed renewal applications is that it blocks any other party from applying for mineral rights in that area.’ In theory, things should be running smoothly, seeing that the DMR has been using a centralised online application platform since April 2011.

The South African Mineral Resources Administration Database (SAMRAD) was introduced to streamline and modernise the application process by linking three components: a public viewer portal (for the public to see the availability of land); a geographic information system (for land selection); and a quality management system (for processing and adjudication of applications).

However, in practice the electronic application process is not working the way it should. Access to SAMRAD (via the DMR website) is unstable and intermittent, obliging some applicants to lodge their paperwork manually. Analysts have warned that while the database is a credible initiative, it has inhibited rather than encouraged growth of an already-stressed sector.

To stimulate the industry, South Africa could, for instance, simplify the application process and reduce the red tape for new entrants and potential investors in the early stages of the mining value chain.

‘Prospecting operations are the lifeblood of the mining industry. Without ongoing prospecting, new deposits are not located,’ says Warren Beech, mining head at law firm Hogan Lovells SA. ‘Both reconnaissance and prospecting operations are high-risk operations in the sense that only a small percentage of prospecting operations identify and locate viable reserves.’ Therefore, prospecting must be encouraged if the country wants to enable greenfield exploration and other new mining projects.

Simplifying the application process and requirements could also assist in legalising small-scale and artisanal miners, who are currently excluded because they typically can’t access SAMRAD and can’t comply with the current financial provisions, technical access and environmental compliance requirements.

To complicate matters, there’s a lack of information regarding the location of possible mineral deposits in South Africa.

‘In order to access the mining rights register, you have to file an application at the DMR in terms of the Promotion of Access to Information Act,’ says Manus Booysen, mining partner at Webber Wentzel in Johannesburg.

‘All mining rights are registered with the Mineral and Petroleum Titles Registration Office, but this information is not generally available to the public,’ says Booysen, adding that establishing which areas in South Africa are still available for mineral rights applications is not a simple process. ‘You can only ask for a specific location, not for a general overview of availability.’

Here the argument that the DMR is protecting commercially sensitive information simply doesn’t stick.

‘Yes, a mining work programme contains confidential financial information, such as the mining company’s cash flow forecast or market figures for a particular metal,’ says Booysen. ‘But a cadastre system can be designed exclusively to disclose basic information regarding which areas are held under mining or prospecting rights, and which areas are still available.’

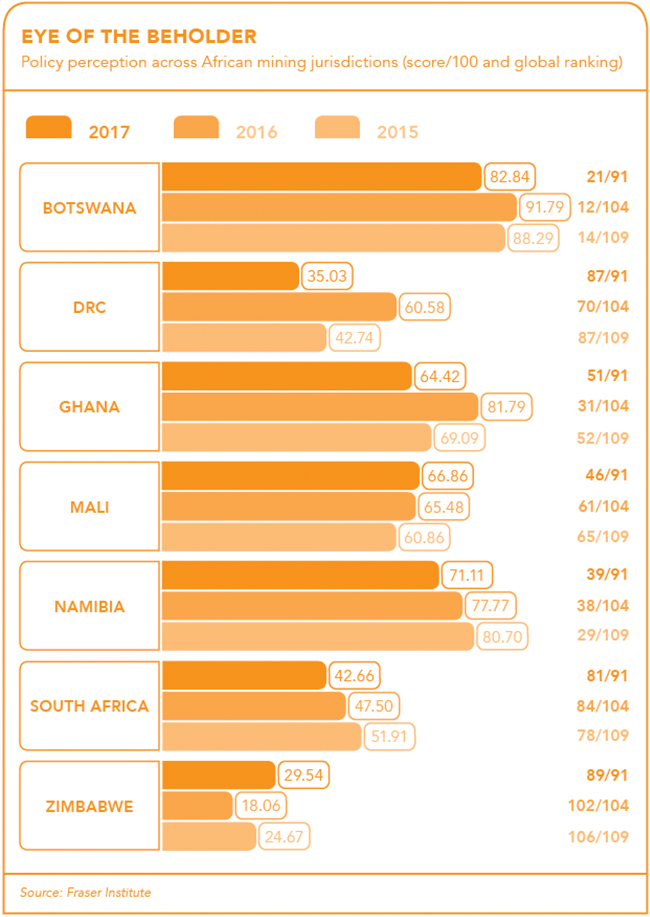

Experts have suggested that South Africa could learn from other African mining jurisdictions, notably Botswana and, to a certain extent, Kenya, which are more transparent and provide the necessary information online at the click of a button.

Neighbouring Mozambique also has an efficient mineral rights-management system, according to Allan Saad, consulting exploration geologist. ‘You just pull up the cadastral map of Mozambique,’ he told Mining Weekly.

‘It tells you who has got the rights, where, when they applied for them, when they lapse, and who owns them, within split seconds.’ In a twist of irony, the article points out that it was a South African company that supplied the cadastre system to Mozambique, while the former government struggles on with its own ‘highly criticised’ SAMRAD.

A well-administrated, real-time online management system also goes a long way towards preventing the double-granting of licences – one of the problems mentioned by Mantashe.

‘On a practical level, an application must be refused if another person holds a right over the same mineral and land, and the current system is not efficient in this regard,’ according to Beech.

‘There are numerous cases where an applicant is granted one of the rights, only to discover that another party already has a right in respect of the same mineral or land. This places both parties in an extremely difficult position, which often has to be referred to the courts for resolution, at great cost to the parties. There are also often anomalies in the rights that are granted, such as the description of the land or minerals, which again leads to disputes.’

Corruption Watch, an NPO affiliated with Transparency International, also strongly recommends that the DMR improve SAMRAD. ‘The proper implementation and administration of an online cadastre system will ensure transparency of information and greatly reduce the possibility of corruption creeping in,’ it states.

In October 2017, the organisation released its report, Mining for Sustainable Development, which outlines weaknesses in the mining rights application process that are giving rise to corruption. The research covers applications of prospecting rights, mining permits, mining rights and environmental authorisations.

Although the MPRDA provides for specific time frames for the processing of applications, these are not consistently adhered to, says the report. The delays deter investors and hinder junior mining companies.

‘It’s taking too long,’ says Booysen. ‘The government should ensure that the DMR is capacitated with regards to manpower, relevant skills and in-depth knowledge of the MPRDA.

‘Currently, the various DMR regional offices interpret the legislative and regulatory provisions very differently,’ he says. ‘The inconstant application of the law results in a plethora of internal appeals and judicial reviews, delays and costs.’

Part of the problem is the high discretion afforded to the DMR as well as the unclear language used in certain regulations and legislation that does not capture the intent of the drafters, which leads to interpretative difficulties. ‘It’s a question of clarifying the legislation,’ says Booysen.

This takes us to the ‘sunrise’ scenario as imagined in the IRR policy paper. ‘By 2028, the MPRDA has been substantially reformed to give South Africa the benefits of stable, predictable and competitive mining regulation,’ writes Jeffery. ‘An efficient, electronic cadastre system has been established, which provides up-to-date information on all new mineral discoveries, the mining and prospecting rights already granted, and the status of all rights applications.

‘The MPRDA’s deadlines for decision-making – two months for prospecting rights and six months for mining rights – are strictly followed. The huge backlogs in decision-making have been cleared.

‘Since the criteria for the granting of rights are certain and objective, the agency’s officials have no power to try and steer either prospecting or mining rights to their “preferred” applicants. A zero-tolerance approach to corruption is also evident.’

Wishful thinking? Perhaps. But while this scenario may seem utopian at the moment, it’s obvious that transparent and efficient mineral licence processes are in the best interests of all mining stakeholders – from government, mining companies, trade unions and host communities to the broader South African economy. Essentially, this is what drives socio-economic growth and attracts much-needed foreign direct investment.

Jaqueline Pinto, mining lawyer at Norton Rose Fulbright, sums up: ‘Investors look for policy certainty and stability at all levels, starting with the basic application process of the mineral rights tenure all the way through to more nuanced policies, because the investment horizons are extremely long and it’s capital-intensive to bring a mine into an operating position.’

According to Corruption Watch, it makes sense to start by getting the mining rights application process right, because it’s one of the first points of call in the mining chain. A clear, streamlined and well-administered application process is likely to decrease corruption further down the line. This, in turn, could form the tentative beginning of a sunrise in South African mining.