There’s no such thing as ‘good timing’ when it comes to fatal accidents in the workplace. But when the news broke, in mid-October 2018, that two mineworkers had died in unrelated incidents at Dishaba mine near Thabazimbi, in South Africa’s Limpopo province, and at Kopanang mine on the West Rand, the timing was particularly bad. News of those deaths hung heavily in the air over the two-day Mine Health and Safety Summit, taking place at the same time near Johannesburg.

It made the words of Minerals Council South Africa (MCSA) vice-president Neal Froneman, speaking at the summit, ring even louder: ‘Our industry cannot rest until the goal of zero harm becomes a reality.’

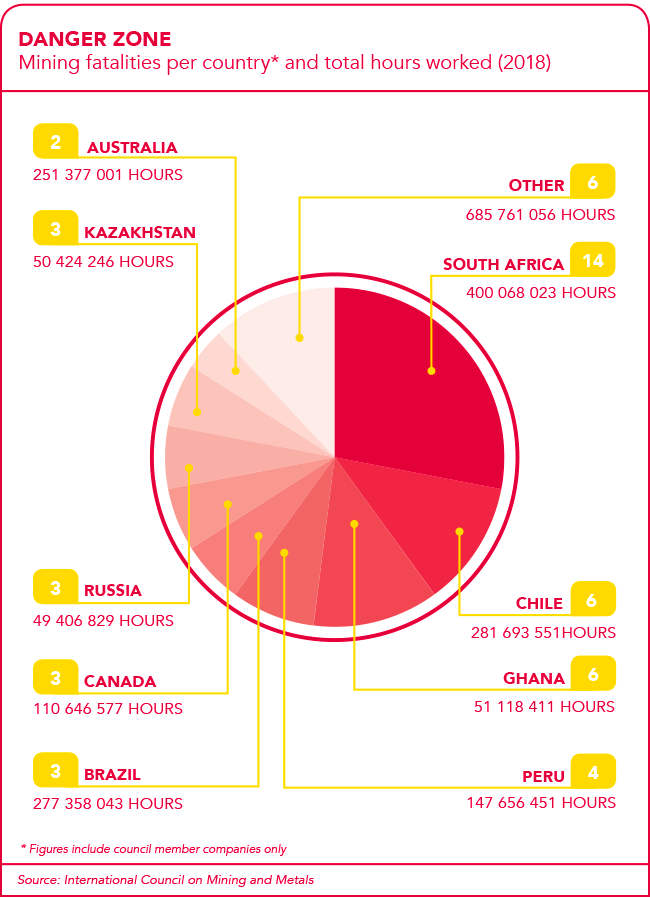

Within a year, South Africa’s mining industry appeared to have taken a giant leap towards that goal. In September 2019, the council reported that the local industry had seen 35 fatalities in the year to date – significantly down on the 63 reported over the same period in 2018. (By the end of 2018 that figure had risen to 81.)

The past 25 years have seen a steady reduction in the number of fatalities in South Africa’s mines, and in mines across the world, driven largely by tightened industry regulations and labour legislation. This has brought our mines closer to zero harm (after all, the figure in 1993 was an horrific 615 deaths), but 35 deaths are still 35 deaths too many.

Every miner has the right to return home safely after their shift, but is the industry goal of zero fatalities by 2024 even possible? Mining is, of course, an inherently hazardous operation – both in large and small-scale mines. Once you’ve dropped down that mine shaft, you’re exposed to risks that range from fires to flooding to fall of ground; from cramped spaces and dust-filled air to heavy machinery and vehicles that you can’t always see – or that can’t see you.

MCSA president Mxolisi Mgojo suggested a way forward during his keynote address and further remarks at the Joburg Indaba in October 2019. ‘I think we’ve put the building blocks in place in terms of how we should look at safety and health into the future,’ he said. ‘I think also we need to accept that there are new ways you can address the issues by adopting new technologies. Therefore, I would be encouraging all of us to continue to understand how we can leverage technologies to drive down our safety and health issues.’

Mgojo acknowledged that there have been significant improvements in safety and health performance over the past two decades, but insisted that a step-change is needed for zero harm. ‘There are a lot of resources still there in the ground and a lot of them are inaccessible from a safety point of view,’ he said. ‘Therefore, with the utilisation of new technologies that we can implement, we can continue making this industry a sunrise industry while at the same time addressing these issues.’

Frederick Cawood is director of the Wits Mining Institute (WMI) at the University of the Witwatersrand, and a firm believer in the power of technology to save lives in South Africa’s mines. In his foreword to the new Best Practice Report on Health and Safety on South African Mines, launched in August by the Southern African-German Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Cawood writes that while much of the global conversation on the future of mining is dominated by the Fourth Industrial Revolution, mining professionals are deeply aware of the immediate challenges.

‘At the top of the agenda is intelligent, precise mining that causes no harm to mineworkers and their communities,’ he says. ‘Miners are faced with countless risks every day – rock falls, working with and in the vicinity of heavy machinery, and health risks that arise from poor working and living conditions,’ according to Cawood.

He adds, however, that digital technologies have the potential to take mining to the next level when it comes to health and safety, pointing to WMI’s collaboration with Sibanye-Stillwater to build the Digital Mining Laboratory (DigiMine) – ‘a 21st century, state-of-the-art’ mining facility suitable for doing health and safety research in a controlled environment.

‘DigiMine is equipped with digital systems to enable research for the mine of the future and is a one-of-a-kind laboratory with a significant research agenda to transfer surface digital technologies into the underground environment – the enabler for a mine that can automatically observe, evaluate and take action.

The ultimate objective is to use technology to put distance between mineworkers and the typical risks they are exposed to on a daily basis,’ says Cawood. ‘Once these technologies are in place and work reliably, we will be able to “see” risks more clearly and communicate their location to the workers. More importantly, technology can “navigate” the individual to safety.’

The Mine Health and Safety Council reports that fall of ground (FOG) fatalities contribute roughly one-third of fatalities in the mining sector (36% in 2016; 37% in 2017; and 27% in 2018). In fact, those two deaths in October 2018 were related to FOG.

That high proportion is consistent with the realities of modern-day mining: for more than a century, the most economically feasible and most productive method of extracting the ore body has been through blasting operations. That’s why, when the MCSA established its CEOs Elimination of Fatalities Team in 2012 (later renamed the CEO Zero Harm Forum), its first area of focus was FOG.

One way to deal with FOG is through advanced illumination. Underground mines are incredibly difficult to light up, on account of the dust and confined spaces, and the non-reflective rock-face surfaces that provide poor visual contrasts. Without adequate visibility, miners struggle to see the visual cues that warn them of slipping, tripping, pinning and striking hazards – and FOG.

A range of headlamp technologies is helping address that problem. The Best Practice Report, for example, showcases the Schauenburg SCAS II Schaulicht SmartLite, which is fitted with a dual-band data radio and an LCD display module that allow user-configurable text messages to be dispatched from the control room to a specific user or group of users.

Its environmental-monitoring graphical user interface allows control-room operators to be warned of dangerous underground conditions such as gas build-up, fires or seismic movement, letting them communicate those threats back to underground personnel in near real-time through the lamp’s full two-way communication technology.

Poor visibility also contributes to mining’s relatively high rates of collisions. In the US, the National Institution for Occupational Safety and Health attributed more than 40% of the industry’s most serious injuries to accidents classified as ‘struck by or caught in machinery and powered haulage equipment’. This makes proximity-warning systems – especially wearables, which tell people where machines are and machines where people are – a vital area of safety technology innovation.

North America-based Carroll Technologies Group is an industry leader in this respect, developing automatic monitoring and alerts that provide additional visibility without distracting mineworkers. ‘To help minimise those risks, visuals are important [as is] a collision-avoidance system, because you can’t always have visuals on where everything is,’ Carroll Engineering president Allen Haywood told Mining Technology. ‘Let’s say you have a large loader that is moving forward and backward all the time, or loading trucks, a crusher or a loading facility. There is no way that the operator can see what’s behind him, that is in close proximity.’

The company’s dash-mounted PAS-Z Proximity Alert System alerts drivers to the presence and proximity of people, obstacles and other vehicles. In dark and dusty environments, this enables a level of vision that the human eye simply cannot offer.

Martin Provencher, industry principal at US software company OSIsoft, notes that many mining companies already have access to life-saving technologies. ‘They in most cases already have the tools. They are just not using them.’

He uses the example of smartphones and personal fitness trackers, which are a fairly common sight in gyms and offices above ground, yet could also help control rooms to monitor miners’ health. ‘If you want to monitor the heartbeat of an employee working 5 km down below, you can just have them wear a FitBit and it’s easy to gather the information. Then there is an alarm that tells me I have one guy 5 km below that’s having a heart issue, send the emergency team there,’ he says.

That kind of thinking is becoming more widespread as the industry turns to technology to limit injuries and fatalities, and to achieve that goal of zero harm. In South Africa, one union leader recently called for mining CEOs to be held personally, criminally responsible for the death of any mineworker.

Mineral Resources Minister Gwede Mantashe immediately dismissed the idea (‘If there is an arrest every single time a person is injured or dies there will be no one left to run the industry,’ he said), but the broader point was already on the industry radar. Mineworkers demand – and are entitled to – safer working environments. To that end, 34 South African mining CEOs gathered at the beginning of 2019 to launch a new safety strategy: Khumbul’ekhaya (Nguni for ‘remember home’).

That, together with ongoing work by the WMI, the Mandela Mining Precinct and the CEO Zero Harm Forum, has already seen South Africa’s mines become – statistically, at least – less deadly. It’s not yet down to zero, but it’s a start.