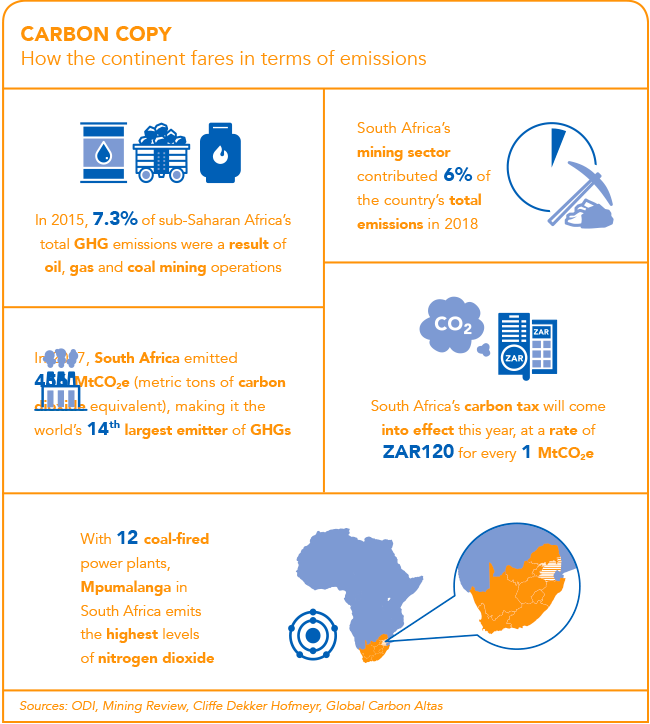

Mining requires vast amounts of energy. Whether it is shallow, opencast mining using heavy haul trucks running on diesel, or deep underground mining that needs electricity (generated largely from coal in South Africa) for haulage, cooling and dewatering, the industry is a major contributor to green-house gas emissions and global warming.

Coal mining is a culprit on three fronts: it generates emissions from its operations, like other mining activities, but it also releases fugitive methane gas and provides a carbon-based product for electricity generation. In June last year, 288 institutional investors, representing US$26 trillion of assets under management, called on G7 leaders to phase out coal in energy generation, as they said governments’ current plans to limit emissions were too weak. The group included Allianz Global Investors, Nomura Asset Management, HSBC Global Asset Management, CalPERS and other US pension funds.

Anglo American has operated coal mines in South Africa and Australia for decades. In its latest climate change report, CEO Mark Cutifani argues that the company was ‘unlikely to make any significant future commitments to thermal coal in the long term’. Coal, he says, is still expected to remain an important part of the energy mix up to 2040 because it has a critical role, through electricity production, in alleviating poverty and sustaining prosperity. ‘It would be detrimental to the development prospects of many of the world’s emerging economies and poorest countries, to simply stop mining coal. That said, fossil fuels will be increasingly contested by society and, as a result, the role of thermal coal will decline.’

However, the global roll-out of alternative energy – solar and wind generation, as well as electric vehicles – is likely to boost demand for many other minerals. These include iron ore, aluminium, copper, platinum group metals and various metals used in batteries. So no one is suggesting a need to disinvest from the mining sector in general – in fact, the reverse. ‘The low-carbon transition of the South African economy is often portrayed as being in conflict with mining and, as such, is criticised for being “anti-development”,’ the WWF notes in a 2018 paper. ‘However, the transition is actually contingent on the availability of the metals and minerals necessary for the manufacturing of clean technologies.’

Improving energy efficiency and switching to renewable sources make sense for mining companies in several ways: it is good for the environment, stimulates demand for their products and, in South Africa (where electricity supply is unreliable and increasingly expensive) it can help save money. According to the International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM), whose member companies include African Rainbow Minerals, BHP, Anglo American, South32, Vale, Lonmin, Gold Fields, Glencore and AngloGold Ashanti, about half of the emissions from mining and processing are Scope 1. That refers to the use of fuel in operations and fugitive methane emissions from coal mines. The other half is Scope 2, which refers to the use of electricity, mostly in refining and smelting.

‘Implementation of cost-effective energy efficiency has the dual benefit of reducing operational greenhouse gas emissions while improving productivity and reducing costs,’ it states. The ICMM says its members are conducting studies into how they can reduce their greenhouse gas emissions and use natural resources (including water) more efficiently, supporting research into industry-appropriate technologies, and measuring and reporting on their progress.

Gold Fields, which operates gold mines in South Africa, Australia and South America, says energy accounted for 17% of operating costs in 2017 and 19% in 2016. In 2017 it started to align its integrated energy and carbon-management guideline with the global energy-management standard, ISO 50001. Energy and carbon management is now part of the operational and strategic approach to the business. It promotes energy awareness and provides training for staff and contractors. In addition, independent auditors collate its energy and carbon emissions data.

Between 2018 and 2020, Gold Fields is aiming for a 5% to 10% saving on its annual energy consumption and a 17% reduction in carbon emissions. This would be a saving of about 800 000 tons of CO2-equivalent carbon emissions in the three-year period. Global gold miner Barrick has also set ambitious targets to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions. Its goal is to keep its current emissions flat in the short term and reduce them by 30% by 2030, from a 2016 baseline of 3.5 million tons of CO2-equivalent emitted. ‘This target is also closely aligned with the national targets set by many of our host governments,’ it notes.

Meanwhile, Cutifani says Anglo American’s ultimate goal is ‘waterless, carbon-neutral mines’. Several years ago the group launched an energy- and carbon-management programme called ECO2MAN, which identifies where energy is being used and how to improve practices. Anglo American intends to improve its energy use by 8% and save 22% of its greenhouse gas emissions by 2020, measured against the projected ‘business as usual’ consumption.

In 2017, Anglo’s board approved the inclusion of these targets within the long-term incentive plan for top executives. For 2030, Anglo has set the bar even higher. By then, it intends to reduce net greenhouse gas emissions and improve energy efficiency by 30% each, and to reduce abstraction of fresh water in water-scarce regions by 50%.

Some of the energy-saving projects Gold Fields has undertaken include commissioning a 40 MW solar PV plant at its South Deep mine in South Africa, which will be built and operated by an independent company, providing about a fifth of South Deep’s electricity at a competitive tariff. At the group’s Sandton head office, it has installed 128 kW of solar panels, which reduced the cost of grid electricity by 45% between 2015 and 2017. The group has also switched to gas-fired power at its Tarkwa and Damang mines in West Africa, and its Granny Smith and Gruyere mines in Australia.

Sibanye-Stillwater, which took over the Kloof and Driefontein mines from Gold Fields a few years ago, has also completed a pre-feasibility study on a 150 MW solar PV plant that would help to supply power to those operations.

In 2016, Anglo American reduced energy consumption by 5.8 million gigajoules. It did this by implementing 320 energy-efficiency and business improvement projects, which saved an estimated US$90 million.

Anglo’s subsidiary Kumba Iron Ore, which uses diesel-powered haulage trucks in its Northern Cape open-pit mines, has made significant energy savings through improving payload-management systems, rolling out a diesel-energy-efficiency management programme, optimising the loading of haul trucks and adjusting haul truck engines.

At Anglo’s metallurgical coal mines in Australia, it has saved greenhouse gas emissions by capturing and using coal-mine methane for power generation. Two methane-fired power stations at Moranbah North and Capcoal, operated by an independent company, together generate more than 100 MW. Combined, these two power stations cut 3.7 million tons of CO2-equivalent emissions annually.

At Anglo’s subsidiary De Beers, there is a study under way into mineral carbonation, which is a naturally occurring process in which CO2 binds to rock, although it is normally too slow to offset CO2 emitted by human activity. De Beers is looking into accelerating the process of carbonate mineral formation in kimberlite tailings, the waste rock from diamond mining, as a form of carbon capture and storage. The study is currently taking place at Venetia mine in South Africa and Gahcho Kué in Canada. Anglo American has also invested, through AP Ventures, in a company called Greyrock Energy, which has developed a technology that converts waste gas, routinely flared at oil production sites around the world, directly into liquid fuels.

If Greyrock’s solution could address a mere 5% of the natural gas that is flared worldwide, it would offset Anglo American’s entire Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions. Global miner and trader Glencore has run a pilot study at its Boshoek ferroalloys smelter in South Africa to generate electricity from waste gases. It showed that Boshoek could reduce its Scope 2 emissions every year by 8% or 60 000 tons of greenhouse gases.

Last year, Glencore implemented another project that will see a second wind turbine being added at its Raglan mine in Canada. The first wind turbine is estimated to have saved 2.2 million litres of diesel, equivalent to taking 1 350 vehicles off the road. ‘Mining is at the heart of the South African economy, and will remain crucial for the low-carbon transition in the country,’ according to the WWF. Irrespective of the future mix of low-carbon technologies, the demand for metals and minerals will abound. South Africa needs to embrace this opportunity to revive its mining industry to become a leader in the manufacturing of low-carbon technologies, to re-industrialise its economy.’