‘More than 90% of our end-consumers are women,’ says Deirdre Lingenfelder, head of safety and sustainable development at diamond mining group De Beers. It seems therefore fitting that an increasing proportion of the people wresting the diamonds from the ground are women too.

Companies dealing in extractive commodities – diamonds as well as gold, platinum, iron ore, zinc, manganese, coal and others – have stepped up their programmes to recruit, fast track and retain more women at all levels of their operations, from underground labour to senior management.

‘Around 24% of our workforce is female, a quarter of our management positions are occupied by women, and our South African mining company De Beers Consolidated Mines has been named South Africa’s Top Gender Empowered Company in the resources category,’ says Lingenfelder, who after nearly 20 years in the mining sector finds that attitudes are changing for the benefit of women as well as broader diversity.

This is partly driven by legislation, such as the Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act and the Mining Charter, and partly by the understanding that companies with women among their senior leadership perform better in terms of profitability, return on investment and innovation.

Globally, South Africa stands out as the only mining jurisdiction with active legislation addressing diversity in the workplace and in management.

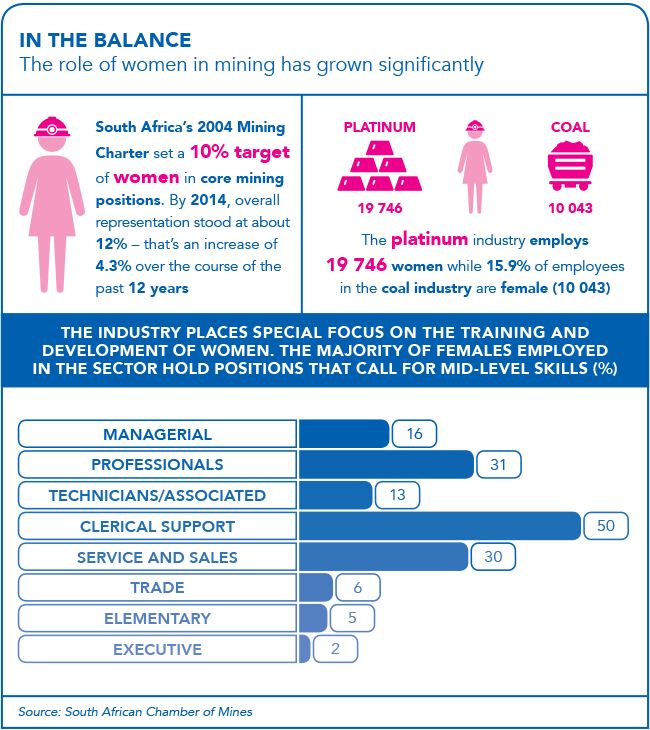

The Mining Charter’s initial target of 10% female representation in mining has been met, and in many cases exceeded, by the industry. However, in April 2016, the new draft Mining Charter dramatically increased employment targets to a minimum of 30% black women in senior management positions, 38% in middle management and 44% of black females in junior management.

Former Mining Minister Susan Shabangu said in a 2012 speech that demographic representation ‘must effectively mean that women will enjoy 52% representation at all levels of the mining sector in time. This is consistent with the societal characteristic, dealing with race also, which we in South Africa are working towards’.

At present, this percentage is still a very long way off. True, South Africa has caught up with the rest of the world in terms of gender diversity since legally allowing women miners to work underground – a restriction that was lifted only in 1997. Furthermore, NPO Women in Mining (WIM) UK and PwC found in their 2015 Mining for Talent survey: ‘South Africa has consistently remained the jurisdiction with the highest percentage of women on boards of listed mining companies trading on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE).

‘The three-year trend of women on JSE-listed mining company boards in the top 100 shows a relatively stable position [17.4% in 2014], with a slight decrease in the last year.’

International Women in Mining – an organisation with more than 9 000 members and 45 groups around the world, aims to increase the number of women in the industry and serving on boards. It is built on mentorship, training and networking.

Noleen Pauls, chairperson of the organisation’s local group, Women in Mining South Africa (WIMSA), says that the prospects for women in mining are great.

‘Approximately 61% of graduates coming into the marketplace are women, slightly less in purely technical fields, so the pipeline is growing. Mining companies are coming increasingly onboard with tertiary education bursaries and training programmes, empowering women through career advancement,’ she says, adding that female representation in mining in South Africa has doubled from 7% in 1994 to 14% in 2014. But owing to the overall slump in the sector, this percentage had contracted to 10% by the end of 2015.

Pauls is optimistic that the gender targets will be on track again, as soon as the cyclical downturn of the sector picks up.

Claire McMaster, head of HR at mining exploration and consultancy firm MSA and a previous WIMSA chairperson, says: ‘If you look at the numbers in the context of the shrinking mining industry, they’re acceptable. There are currently fewer jobs in mining but the majority of women have managed to hang on to their jobs.’

Claire McMaster, head of HR at mining exploration and consultancy firm MSA and a previous WIMSA chairperson, says: ‘If you look at the numbers in the context of the shrinking mining industry, they’re acceptable. There are currently fewer jobs in mining but the majority of women have managed to hang on to their jobs.’

While much has changed for the better, women are still held back by the male-dominated culture of the sector. Respondents in the Mining for Talent survey cited the ‘boys’ club mentality’ and ‘lack of senior management commitment to diversity’ as some of the key obstacles blocking their career path.

Nowadays sexism may not be as blatant as it once was, but gender bias still exists – even among women themselves.

McMaster says that many mining houses offer gender-sensitivity training to employees and management at all levels, which is often grouped with diversity-sensitivity training and frequently takes place under the umbrella of the company’s transformation programme. This has been shown to tackle unconscious bias.

‘People generally don’t realise how biased they are, and how much they are led by stereotypical thinking,’ she says, adding that a change of company culture regarding attitudes towards gender and diversity needs to be driven from the top down to be effective.

Lingenfelder underlines the importance of mentorship and networking. ‘I have, in the past, experienced the negative perceptions around gender and age. It required me to work that much harder in gaining and keeping the respect and support that might in other situations automatically be granted.

‘I have gone to great lengths to establish a network of support, from career mentors and other women in mining – we call each other ’wing women’ – to subject-matter experts.’

Anglo American Coal SA is one of the companies to have set up a successful mentoring programme for graduates and junior employees. The programme is open to everybody, but the proportion of women mentees is particularly high.

An internal database is used to collect details of those wanting to find – or become – a mentor. The HR team provides mentorship guidelines and matches mentors with mentees.

Philip Williamson, the company’s head of HR, says: ‘Having a nominations page for mentorship, both as mentors and as mentees, meant that the mentors who put themselves up were far more committed to the programme. Consequently, they were motivated and actively interested in their mentees and helping them progress.’

According to Pauls, female graduates prefer female mentors as they share similar challenges and feel they can relate better. ‘As the younger generation of graduates climb the corporate ladder within mining companies, the amount of female mentors will increase, addressing this issue,’ she says.

Another challenge that specifically affects women in underground and core mining jobs is safety and sexual harassment.

‘Working relationships with male mineworkers are often not easy. The view among many men, including those who would ordinarily consider themselves progressive-thinking, is that women don’t belong underground,’ South African Chamber of Mines president Mike Teke told a WIMSA workshop.

He added it was paramount to keep women safe in their workplace, especially where one or two women were working among several hundred men. ‘Some of the initiatives implemented as a result of the chamber-led task team include “buddy” systems, panic buttons, two-way radios, tracking systems, securing vulnerable areas on a mine, sealing off abandoned areas, self-defence training, regular visits by supervisors and an intimidation hotline.’

De Beers employees, for instance, have access to channels to voice anonymous concerns, and Anglo American Platinum has a sexual harassment hotline, surveillance cameras and biometric access control to women’s changing rooms. Sibanye Gold has established a task team to develop strategies to attract more women and address the personal safety and integration of female employees into male-dominated working teams.

Impala Platinum has a ‘women in mining’ safety forum in Rustenburg that meets monthly to identify and address safety and health issues. The company has also recently improved the availability and quality of specialised personal protective equipment for women.

Teke said that ensuring women’s safety also meant providing them with appropriate clothing and equipment: ‘Overalls need to be a different shape to men’s – and concepts like side slits for additional ventilation make life difficult for women, and may mean they have to wear even more clothing, defeating the purpose.

‘Sizing is entirely different too – a small woman is unlikely to be able to work comfortably in an overall meant for a small man. Webbing and strapping for safety and other equipment will sit differently – and sometimes problematically – on a woman’s body.’

Most mining houses have already listened to their female workforce and introduced separate ablution facilities, women-specific personal protective clothing and ergonomically correct equipment.

Their efforts have gone a long way towards improving the opportunities for women in South Africa’s mining sector – an area where much has been achieved already but where so much more still needs to be done.