While the coronavirus gradually recedes from news headlines, and widespread vaccination reduces both infection rates and symptom severity, industry sectors are focusing on economic recovery and returning to a semblance of normalcy. For mining companies, the COVID crisis is more or less over, which means greater resources can be returned to pre-existing health needs of workers and their communities. And those needs are very real.

Apart from the high risk of injury, mineworkers are inordinately affected by respiratory disorders, heart disease and cancer. These various risks affect not only workers … but also their families and people living around mines.

People are drawn by the potential income of mine-related activities, and unplanned settlements grow, reports Equinet Africa, a regional network on equity in health in East and Southern Africa. This can lead to the spread of infectious diseases such as TB and HIV, and raise the risk of epidemics, such as cholera and typhoid.

‘Because of [its] impact on people, the environment, and social systems, mining [has] both an obligation and responsibility to look after the health of communities. This accountability and responsibility is also enshrined in legislation,’ says Reana Rossouw, owner of Next Generation, a sustainable business consultancy. ‘Mining companies generally focus on two things – access to primary healthcare services and quality of healthcare services. They and their stakeholders – employees and communities, broadly – are also affected by any lack of service delivery by government.

‘For this reason, access and quality form the basis of their healthcare interventions. So typically this plays out in building clinics or hospitals and the provision of services, including resources and staff, and may in some cases be supplemented with additional services such as counselling, access to ARVs, access to family planning, and so on.’

About a third of global unexploited mineral resources are located in sub-Saharan Africa, yet health-related markers for sustainable development are ‘lagging behind’. For African mineworkers and their communities, the benefit of jobs, skills and income is offset by substantial risks, and while occupational health and ESG regulations specific to the mining sector are in place to address these challenges, some organisations and industry bodies have for a while been directing their social investment budgets towards more comprehensive health services.

‘The provision of occupational health services is a statutory obligation,’ according to Thuthula Balfour, head of health at the Minerals Council South Africa (MCSA). ‘Most companies, however, follow a wellness approach and offer medical aid to their employees or have wellness clinics. Diseases such as TB and HIV are monitored and reported on by the industry, and the Minerals Council has a reporting system available to any company that wants to use it,’ she says.

‘Employees are part of a family and community. Diseases such as TB are communicable and it therefore makes business sense to be involved in lowering the risk of disease in the community. The same goes for mental health where the causes are psychosocial. Mental health is a bigger priority than a few years ago, and poor mental health was exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

‘In October 2022, the CEO Zero Harm Forum reviewed the state of mental health in the industry and adopted the WHO Mental Health at Work Brief, which promotes the creation of a supportive environment for mental health in the workplace.’

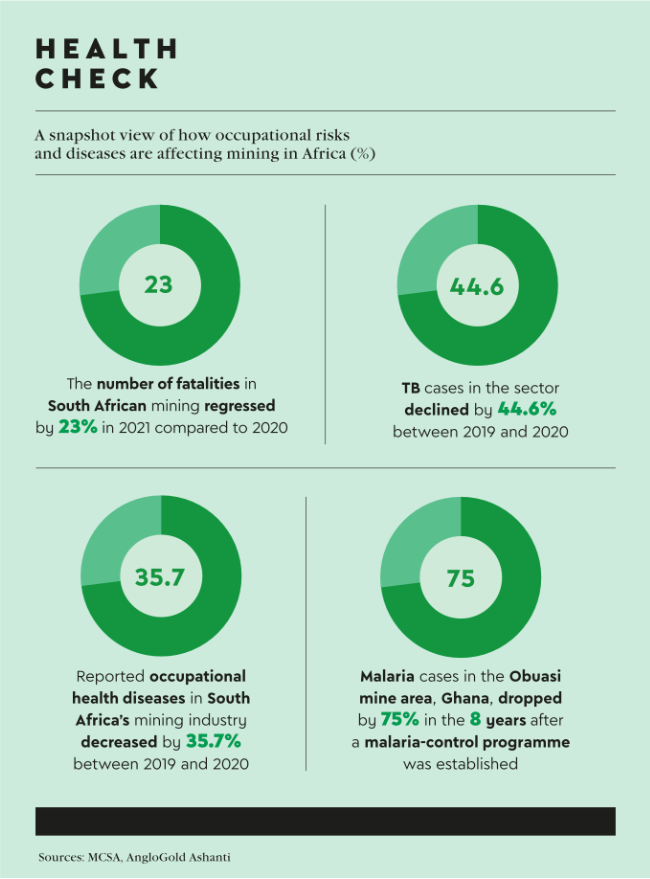

Founded in 2012, the forum brings together industry CEOs to address health and safety challenges and accelerate the sector’s ‘journey to zero harm’. While the overarching impact has been a huge reduction in fatalities since inception – most recently, a 35.7% decrease in reported occupational health diseases to 2 013 in 2020 from 3 130 in 2019 – safety performance regressed in 2021 for the second consecutive year, with a 23% increase in reported fatalities, compared to 2020.

The decline in diseases across all categories shows interventions are working, with the biggest decline seen in coal worker’s pneumoconiosis and pulmonary TB. The industry has seen a 44.6% decline in cases of TB to 849 in 2020 from 1 533 in 2019 – a commendable achievement considering that in South Africa, a global TB hot spot, prisons and the mining industry have the highest transmission rate.

That drop may be credited to another MCSA initiative, Masoyise iTB, a multi-stakeholder programme established in response to the high rates of TB and HIV among miners. It includes representatives from trade unions, government and other organisations, all of which worked closely to reach the project’s goals.

Between 2016 and 2019, Masoyise iTB achieved targets including making annual TB screening and HIV testing and counselling available to all mining employees; monitoring screening performance for TB and HIV; and conducting TB contact tracing exercises.

Masoyise iTB continued in 2019 as the Masoyise Health programme, which has a wider mandate beyond TB and HIV to include non-communicable diseases, and is currently set to run until 2024.

While Southern African mines battle TB, countries further north face a different foe – malaria, which remains one of the biggest health challenges in sub-Saharan Africa.

Endeavour Mining, which owns and operates gold mines in Côte d’Ivoire, Burkina Faso and Senegal, has partnered with the Ministry of Health and Public Hygiene in Burkina Faso to make Dangouna village malaria-free by June 2023. The protocol was signed in April 2022, and its pilot project will benefit more than 1 150 people in the village, aiming to reduce the incidence of malaria by 90% by February 2023 and to achieve a 0% malaria mortality rate by June.

Endeavour Mining’s pre-existing malaria-control programme includes providing mosquito nets to the communities in which it operates, residual spraying inside homes and buildings, and reducing the amount of stagnant water on site, which is a breeding ground for the insects.

It isn’t the first – AngloGold Ashanti set up its malaria-control programme in Ghana in 2014, AGAMal, which saw a 75% drop in cases in the Obuasi mine area in just eight years.

‘In my personal opinion, mining companies bear a big responsibility for the health of their workers and communities,’ says Rossouw. ‘However we should also recognise that from an economic perspective – this responsibility and contribution to the broader context of ESG challenges – is a declining responsibility.

‘I think [mining companies] are doing a lot – and the South African government and economy has become very dependent on the additional support it gets from the mining sector, over and above their taxes and income. But let’s face it, the traditional large mining companies no longer operate the way they used to.’

Rossouw points out that Anglo American was instrumental in designing and developing the Impact Catalyst as a way to mitigate the impact of divesting and closing down mines. Co-founded with the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, Exxaro and World Vision South Africa, the initiative counts as one of its projects the Community Oriented Primary Care programme, which was initially developed by the department of family medicine at the University of Pretoria, and has been successful in several municipalities.

‘Our most important priority is to ensure that everyone is better off and healthier having worked for Anglo American,’ says Charles Mbekeni, health lead for Southern Africa at Anglo American. ‘We need our people to be healthy, happy, engaged and fulfilled in work and life. It makes us safer, more productive, and a stronger force for good in the communities where we operate.

‘We tackle the threats to health and well-being wherever we find them, with separate programmes for physical and mental health – including our Living with Dignity programme to tackle the scourge of gender-based and domestic violence prevalent around the world – for creating a healthier working environment, and for encouraging healthy lifestyles.’