Golden sunflowers sway in the fields surrounding the Geita gold mine in north-western Tanzania. Despite ideal climatic conditions, this crop had never been cultivated in the area until AngloGold Ashanti (AGA) encouraged local farmers to plant sunflowers as part of its CSI initiative. The miner’s five-year Geita Economic Development Programme intends to stimulate employment creation and income generation in the host communities near the company’s open-pit gold mine.

In addition to the sunflower co-operative, which produces oil, seeds and animal feed, the programme – currently in its third year – has achieved measurable success in rice paddy cultivation.

In an effort to commercialise and upscale smallholder farmers, AGA established large-scale rice farming in the villages of Saragulwa and Nungwe, approximately 20 km from the mine. About 980 farmers are involved in the paddy co-operative, which cultivated 125 ha of land in 2016 and extended that to around 350 ha in 2017.

‘Geita gold mine brought in professionals to train us in modern farming with good technologies,’ says Judah David Ng’hindi, chairman of the Saragulwa village, in a company video. ‘We observed that good seeds increase our yields from about nine to 15 bags of rice per hectare. Geita is building us a big store to keep our harvests and a brand new machine to process our harvests. They have also assured us they will bring seeds and fertilisers.’

According to AGA’s 2017 sustainable development report, local farmers had been cultivating rice from traditional seed varieties in these fields for decades. Since the inception of the CSI project, their yields have increased by up to 225% as a result of improved seed quality and modern agricultural techniques.

In 2017, Geita completed the construction of a modern storage facility that enables farmers to sell their produce throughout the year and take advantage of seasonal price fluctuations. The mine also intends for farmers to partner in an irrigation scheme that uses water from nearby Lake Victoria, to ensure the sustainability of its economic development programme.

AGA says it closely monitors the progress of the programme and transfers the learnings to its other operating jurisdictions – in this case from Tanzania to Ghana and Guinea. In total the company spent US$24.1 million on community investment across its operations in 2017 – up from US$20.2 million in 2016.

Most mining companies have by now recognised the inextricable relationship between mines and their host and labour-sending communities. The success of a mine can’t be separated from the socio-economic situation of its workforce and the people living around it. Therefore the industry leaders go far beyond the requirements needed to maintain their licence to operate, which in South Africa is legislated through social and labour plans (SLPs).

Companies such as Anglo American, AGA, Exxaro, Harmony Gold and Impala Platinum (Implats) have articulated their ‘responsible mining’ strategies and, according to Minerals Council South Africa, are spending triple the standard CSI of 1% net profit after tax.

‘Notably, 16 of the 66 operations managed by 28 companies reported financial losses in 2016, yet they collectively contributed more than ZAR180 million to mining community development,’ the council states in its transformation fact sheet.

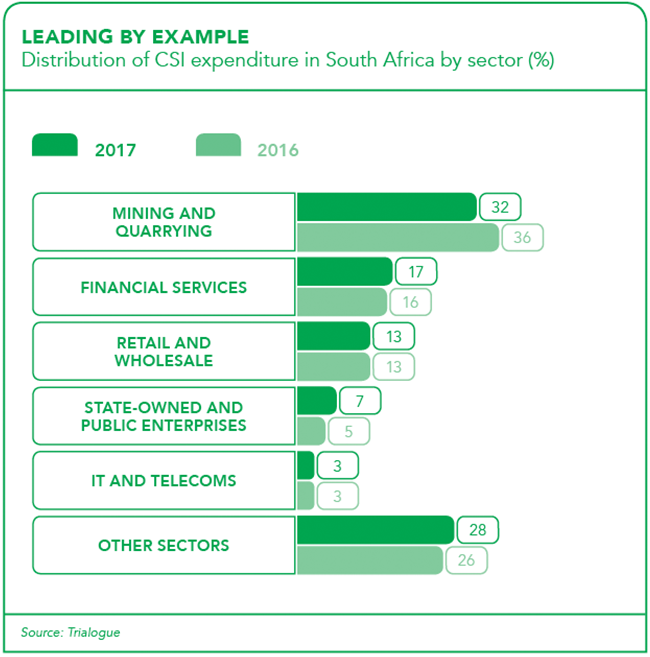

Research by CSI consultancy Trialogue estimates that despite challenging economic conditions, South African companies invested more than ZAR9 billion in CSI during 2016/17 – taking it to a total of ZAR137 billion over the past 20 years. This has been disproportionally driven by the mining and quarrying sector, which still accounts for around one-third of the country’s total CSI spend.

‘The mining industry has an unprecedented opportunity to mobilise significant human, physical, technological and financial resources to advance the Sustainable Development Goals [SDGs],’ according to the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), which recently published an atlas showing the linkages between mining and the SDGs.

The idea is to nudge mining companies of all sizes towards incorporating the relevant development goals into their business and operations.

Mapping Mining SDGs: an Atlas describes the positive and negative impacts of the global mining industry, which tends to be located in remote, ecologically sensitive and less-developed areas.

‘Historically, mining has contributed to many of the challenges that the SDGs are trying to address: environmental degradation; displacement of populations; worsening economic and social inequality; armed conflicts; gender-based violence; tax evasion and corruption; increased risk for many health problems; and the violation of human rights,’ the publication states. ‘In recent decades, the industry has made significant advances in mitigating and managing such impacts and risks by improving how companies manage their environmental and social impacts; protect the health of their workers; achieve energy efficiencies; report on financial flows; and respect and support human rights.’

This means, in the words of the UNEP, that mining ‘can create jobs, spur innovation and bring investment and infrastructure at a game-changing scale over long time horizons’.

Yet the recent economic downturn, coupled with plummeting commodity prices, rising production costs and regulatory uncertainty have severely hampered the industry, and thereby its power to effect socio-economic change.

‘Unfortunately, when the economic environment impacts the mining sector it also affects financial resources to fund CSI programmes. So economic and social growth is impacted,’ says Tracey Henry, CEO of Tshikululu Social Investments.

This presents a serious dilemma, because during an economic slump, CSI is required more than ever, according to Henry. ‘Pressing the pause button can undo a decade of social development and investment. To kick-start this from scratch and gain traction once the economy improves will take years.’

To illustrate her point, she provides the example of CSI initiatives that improve education. ‘Preserving core work in this area is important, because when the economic climate picks up, we will need a pipeline of future professionals – especially those that are ready for new ways of working in an environment that is investing in modern mining technology and automation.’

Another reason mining companies need to keep their CSI programmes running even during restructuring and retrenchments relates to their SLP obligations, which cover five-year periods. Furthermore, miners use social investment to strengthen the relationship with their workforce and host communities in an effort to foster good will and avoid unrest.

Implats is an example of a beleaguered mining company striving to keep its community investments going despite massive restructuring (over the next two years, 13 000 employees and contractors will lose their jobs).

At the time of writing, the 2017/18 CSI figures had not yet been released, but Implats is one of several mining companies that increased their 2016/17 CSI spend, says Paul Pereira from the Institute of Race Relations. Others in this category include AGA, Assmang, BHP Billiton, Glencore Xstrata, Harmony Gold, Lonmin and Gold Fields.

‘Over the 2016/17 financial year, Implats invested ZAR106 million [ZAR105 million in 2015/16: ZAR83 million in 2014/15] in socio-economic development projects, of which 91% was on SLP projects. An additional ZAR265 million was spent on improving accommodation and living conditions of employees,’ says John Nkosi, Implats’ group sustainable development manager.

He adds that more than 24,000 people in South Africa and 4,000 in Zimbabwe have been positively affected by these investments.

‘Close on two-thirds of these benefited from infrastructure projects, including roads in Luka and around Marula, a community hall and offices in Roodekraalspruit, water pumps and early childhood development centres in Marula.’

In line with regional policies for BEE and local content, mining companies in Southern Africa are not only supporting entrepreneurship and community job creation in sectors unrelated to mining (such as Exxaro’s Thusang Bakery project and Harmony Gold’s Doornkop Sewing or Sugar Honey bee farming). They are also increasingly including emerging black-owned SMEs in the mining value chain through supplier development and preferential procurement. Here Anglo American’s long-standing Zimele enterprise development programme is a shining example.

Tebello Chabana, senior executive of transformation at Minerals Council South Africa recently noted that about 50% to 60% of a South African mine’s purchases (consumables, capital goods and services) are now sourced from BEE suppliers.

Strictly speaking, this is not CSI because it forms part of SLP requirements as laid out in the Mining Charter and Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act. But the lines are blurred, and both CSI and SLP have one common goal: the creation of resilient, self-sufficient communities beyond the life of a mine. The key to this is a holistic corporate strategy, community participation and multi-level partnerships.

‘Mining companies cannot change the social upliftment of communities on their own. They are reliant on local municipalities, the broader legislative environment and the economic environment,’ says Henry.

A promising example is a three-tier partnership in South Africa’s AmaMpondo kingdom, Eastern Cape, which empowers local women to become commercial maize farmers. AGA has partnered with brewing giant AB InBev, the OR Tambo District Municipality and local community to promote income generation and food security in this labour-sending region.

The initiative has established three co-operatives with more than 300 land-owners, 51% of whom are female, who support about 5,000 community beneficiaries.

More than 500 ha of maize was planted – and while the first harvest in August 2017 didn’t yield the anticipated results, lessons were learnt and the farmers are now on track to commercial success, according to AGA.

Together with AB InBev, AGA provides joint funding for the fixed assets and operational costs. The brewer has committed to buying the maize from the community co-ops. The gold miner has also facilitated a formal relationship between the community and the Eastern Cape Department of Rural Development.

This has the potential to secure a future off-take partner as well as additional funding to ensure the long-term success of the farmers. The AmaMpondo initiative underlines the crucial role that mining companies play in creating resilient local communities.