Mining is thirsty work: vast quantities of water are needed for ore processing and other operations, as well as for sustaining employees. This creates challenges, particularly in a water-stressed region such as Southern Africa – challenges that can only increase with the pressures of a changing climate.

Globally, the water crisis will be especially intense for the mining industry, says Johanita Kotze, water management lead (Africa and Australia) at Anglo American. ‘More than half of mining investment over the next decade is expected to be in high to extreme water-scarce areas,’ she says. ‘Water consumption for the industry is increasing at more than 5% annually.’

In South Africa, the crisis has two prongs. On the one hand, there is natural water scarcity – the country’s annual rainfall is below the world’s average – which threatens mines’ global competitiveness. On the other, water quality is deteriorating. According to Alan Fine, spokesperson for the Minerals Council South Africa (MCSA), this is due to ‘ailing and mismanaged municipal infrastructure, which leads to deterioration of raw-water quality, thus requiring treatment prior to use’. This in turn increases mining costs.

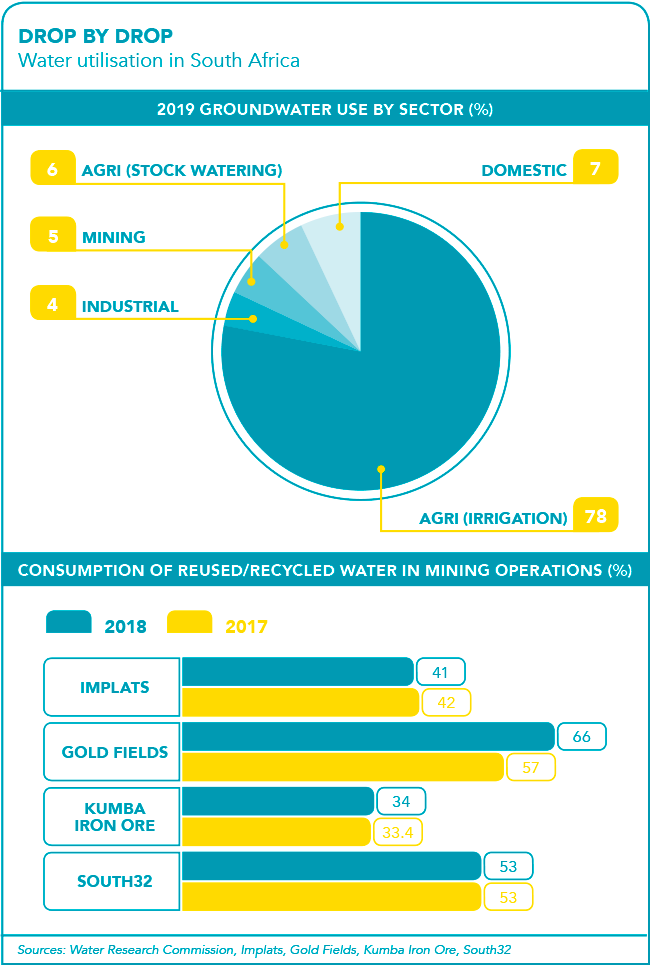

The industry is nothing if not aware of these pressures, and the mines are tackling water scarcity with a variety of strategies – using less water in their processes; recycling water where possible; and disposing of waste-water responsibly. The MCSA, in partnership with South Africa’s Department of Water and Sanitation, has been proactive in prioritising water saving, developing water-use efficiency benchmarks for the mining sector, and drawing up guidelines for managing water resources. Member companies are required to implement water-saving measures, and ‘account for every drop of water that they use within their operation’, according to Fine.

As Mzila Mthenjane, executive head of stakeholder affairs at Exxaro, puts it: ‘Exxaro is not isolated from the water issues that the country is facing. Water plays an integral part [in] our mining operation from exploration and mining beneficiation process, to employee consumption and hygiene. The ultimate objective is to reduce withdrawal of additional potable water from any source and optimise and use our water more efficiently.’

One way to handle the looming crisis is to invest in technological solutions. Many mining companies have successfully implemented state-of-the-art water-saving mechanisms, ranging from new recycling techniques to digital monitoring technologies. ‘The biggest game changer the mining companies are investing in is looking at reducing water losses in tailings,’ says Fine, mentioning innovative evaporation covers for tailings dams and the use of dry stacking – the storage of filtered tailings in dry, sandy form.

Coarse particle flotation (CPF) is another rapidly developing technology that enables mineral recovery from large-sized ore fragments. Coarsening the grind size dramatically reduces the energy required to grind ore, as well as the required water intensity (the amount of water used per unit of ore mined). ‘Where CPF is combined with dry disposal technology, we are targeting a reduction in water intensity of more than 50%,’ says Kotze.

CPF is currently being tested at several of Anglo American’s sites around the world. A 500-ton-per-hour unit, the biggest of its kind, is being piloted at the large Anglo American Platinum (Amplats) open-pit Mogalakwena mine in South Africa’s Limpopo province.

At Mogalakwena and at Amplats’ Der Brochen Mototolo operation, ‘scavenger wells’ – which draw off contaminated water – have been implemented to extract tailings seepage water and reduce contamination of the environment. Another promising technology, horizontal directional drilling, is being piloted at Anglo American’s Los Bronces copper mine in Chile. Directional (as opposed to vertical) drilling allows for more thorough collection of groundwater seepage from the tailings and the seepage plume, thus reducing dependence on external water supplies.

At Exxaro, there is also a focus on recycling. ‘There is a strict hierarchy of water utilisation by prioritising the re-use of process water before utilising fresh water,’ says Mthenjane. This means that dirty runoff, treated sewage water, opencast pit and underground water, as well as seepage from stockpiles and discard dumps is all captured or extracted, and returned to the system for re-use. Exxaro’s Grootegeluk mine in Lephalale, Limpopo, boasts a cyclic-operated pond facility – the first of its kind – for the continuous reclamation of dried coal slimes. This represents a unique approach to the handling of coal fines (discard material with small particle size).

‘The large-scale installation of a sophisticated barrier and drainage system along with the reclamation of the coal fines as a continuous operation are industry firsts and allow for the better reclamation of water back to the process water system,’ says Mthenjane. Also important is the use of computerisation in the ‘digital mine’, to use Kotze’s phrase, for water-data collection, assessment and reporting.

Tools include WIMS (water information-management solution) software and SCADA (supervisory control and data acquisition), a computer system that gathers and analyses data. At Amplats’ Polokwane smelter, ‘the WIMS application is fully integrated into the site SCADA system and now collects water data [in] real time’, according to Kotze.

Other water-saving strategies tackle the problem from the opposite direction: exploring how water displaced or discarded by mining can actually benefit surrounding communities, rather than create environmental damage. Larger mines often supply water to residential areas associated with the operation, such as mine housing units, or to the region in general. Other investments may include building infrastructure such as boreholes, water tanks and reservoirs for use by local inhabitants.

This eases the competition for water resources that often exists between the mining sector and communities in water-scarce areas, and is partly a response to calls for greater social justice. ‘Pressure by NGOs, governments and other social groups highlighting and calling for actions to address the impacts of ground and surface water pollution and the associated infringement of basic human rights is becoming more prevalent,’ says Kotze.

Fine gives as an example South Africa’s Witwatersrand gold mines, which are located in a dolomitic area that is characterised by large volumes of groundwater. ‘This groundwater normally has to be removed and discharged into surface streams and rivers so that the underground mining operation may proceed,’ he says. ‘In such cases, this apparent “additional” water may provide a useful source of water for other surface-water users, for example communities in the catchment area.’

Amplats has played a leading role in assisting municipalities gain access to potable water. In partnership with water utility company Hall Core Water Mapela and the Mogalakwena municipality, it provides 3.5 million litres of potable water daily to more than 70 000 people in nearby communities.

‘Our operations for Coal South Africa and Kumba Iron Ore are water positive and net water providers in the catchments were we operate,’ says Kotze. For example, the eMalahleni water-treatment plant on the Witbank coalfields was built to treat mine-impacted groundwater to a potable water standard, and supplies the municipality. ‘We have also invested and assisted on a much larger scale to help national government to develop the Limpopo Regional Water Strategy, and collaborated on projects such as the De Hoop and Flag Boshielo dams to ensure stable water supply in the province,’ she adds.

In the province of Mpumalanga, Glencore supplies water from its coal operations for use by the local Phola municipality, while Exxaro’s Matla coal mine has been operating a water-treatment plant since 2015. ‘Water is drawn from underground workings and treated to stream-quality level and released to the upper Olifants catchment, where downstream farmers and communities have access to this water,’ says Mthenjane.

With these innovations, there is hope that the mine water crisis can be managed more efficiently in the future. ‘With guidance from government and responsible mining companies, new technologies and good planning, many of the potential impacts and water crisis experienced today are avoidable or could be reduced,’ says Fine.

But there is little doubt that the pressures of water scarcity will continue and intensify. ‘We foresee that water risks will only worsen in the future and have incorporated water management in our business strategy and plans. We are continuously committed to improve our critical monitoring instrumentation, hire more resources and improve our understanding of these complex issues,’ says Kotze, striking a cautious but determined note. ‘We understand that water is a resource and asset, and respectfully manage it as such.’