Soccer City could fall down at any minute. It sounds dramatic, but according to Johannesburg mayor Herman Mashaba, South Africa’s 94 000-seater FNB Stadium – home ground of Kaizer Chiefs FC and venue of the 2010 Fifa World Cup final – is under threat of collapsing due to illegal mining in the surrounding Nasrec area. ‘Investigations have revealed that if illegal mining activity continues within these old mining shafts‚ the entire FNB Nasrec precinct‚ including the iconic FNB Stadium‚ could go down in ruins as a result of unstable earth directly underneath the area,’ Mashaba told the Sowetan in April.

The mayor is right to worry – as anybody involved in mining explosives would tell you. Underground blasting carries risks of tremors that could threaten the structural integrity of surrounding structures, and of sparks that could ignite large fires (a particular concern in the Nasrec area, which has gas and fuel pipelines nearby).

The Soccer City scare gave the mining explosives industry a rare moment in the public eye, and the safety concerns around the illegal blasting highlighted just how far the industry has come. Recent technologies are making mining explosives safer and more controlled than ever before – as three explosives firms are demonstrating.

One of the companies leading the charge in African mining explosives is AEL Mining Services. A member of the JSE-listed AECI Group, it recently launched IntelliShot, an advanced electronic initiating system that it says simplifies blasting operations. ‘The current economic climate leaves no room for error in mining, and companies are unwilling to compromise on safety, expecting the most state-of-the-art and cost-effective solutions,’ Dirk van Soelen, AEL’s global portfolio manager, notes in a statement.

The system can handle a range of blasting complexities and offers three tagging methods, from simple blast designs with fixed delay formats to complex blast designs that use survey co-ordinates. Said to offer a fast and simple deployment method, the set-up also provides autonomous detection and testing of detonators, and energy monitoring right up to the point of blasting.

This removes any uncertainty from the blasting environment, allowing the operator to pre-test the entire detonator network to ensure functionality according to the blast design, and to prevent unforeseen blast delays and outcomes.

IntelliShot can initiate up to 16 000 detonators per blast, meaning the blasting of large patterns or multiple benches is both simple and safe.

One of the most significant parts of the system is the IntelliShot Tagger, a hand-held device that allows the user to conduct on-bench activities such as tagging (which writes the delay and location to the detonator), while also carrying out full functionality tests and creating a blast interface to its companion Commander device during the blasting stage. This allows the Tagger to assist in detonator troubleshooting, while also recording the GPS location of the detonator, and testing up to 400 detonators at a time. ‘This is an unprecedented benchmark in blasting,’ according to Van Soelen. ‘The Tagger is inherently safe, and allows users to troubleshoot the bench before leaving.’

IntelliShot builds on the existing ViewShot 3D design software (developed by AEL’s partner DetNet), which allows users to design, plan and analyse blasts. The ViewShot 3D software can calculate the energy map distribution, optimise delays, predict fragmentation and simulate blast timing using animation.

Remote wireless blasting forms part of the general industry trend towards safety, efficiency and automation. In September, Orica announced the successful production trials of its own wireless electronic blasting system, the WebGen 100.

Orica, which showcased its Blast IQ System at the February 2018 Investing in African Mining Indaba conference in Cape Town, claims that the WebGen 100 ‘signals a step-change in in-hole initiation and a decisive step on the path towards full automation of drill and blast operations’.

The system allows groups of in-hole primers to be wirelessly initiated by a firing command that can communicate through rock, water and air. This is a key point, as it does away with the need for a physical connection to each primer.

Describing the system as ‘a world-first technology’, Orica chief commercial officer Angus Melbourne says it ‘not only improves safety by removing people from harm’s way – it also improves productivity by removing the constraints imposed by wired connections’. He adds that the design ‘is a critical precursor to automating the charging process. The entire industry is moving rapidly towards an automated future’.

Orica is also developing a wireless primer specifically designed for surface mining applications – the first step, the company believes, towards full automation of the drill and blast process across the underground and surface mining sectors.

That industry-wide shift to digital technologies is driving efficiencies in some parts of the mine, and improved safety in others. Blasting is no different – particularly in the move from non-electronic to more flexible electronic delay detonators (EDDs).

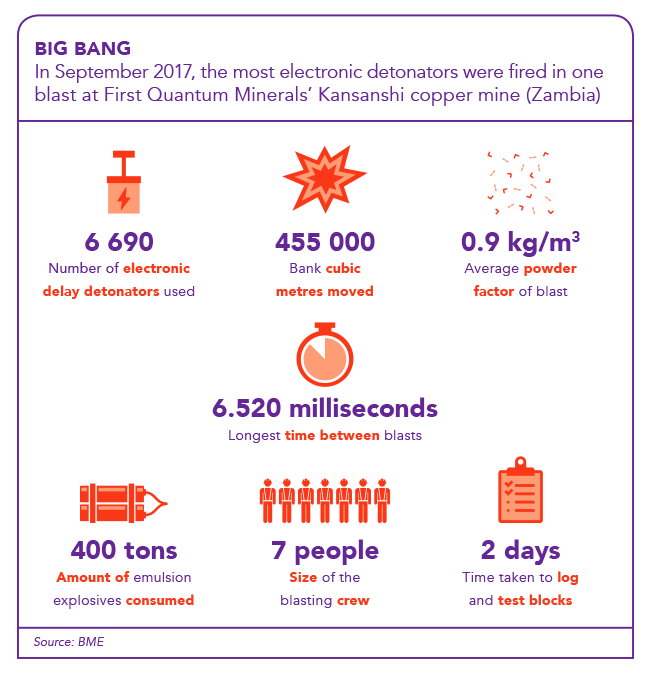

‘When we were first exploring the capability of EDDs, we were impressed by the accuracy that blasting with this technology allowed us,’ according to Tony Rorke, technical director of explosives firm BME. ‘This accuracy and reliability was a huge step forward, ensuring that there were no out-of-sequence blasts.’

Previously, when using non-electric initiation systems, blasting teams would work according to traditional timing conventions – based, Rorke explains, on the fact that accuracy diminished significantly as the length of the pyrotechnic delay elements increased. Misfires during blasts were also known to happen, if down lines were severed before the firing signal reached the detonators.

‘To get the detonators to fire in some acceptable sequence, therefore, delay periods were, in the past, kept as short as possible,’ he says. ‘The longer down-hole delay has the dominant impact of firing time accuracy, so the risk of out-of-sequence initiation is a function of the in-hole detonator. Keeping this as short as possible led to delay periods of between 350 milliseconds and 550 milliseconds becoming standard for in-hole delays in surface blasting.’ This created complications with the time delays: too short a delay, and you risked out-of-sequence firing or blast choking; too long, and you risked cable cut-offs caused by short burning fronts.

‘None of these problems exist with EDDs,’ says Rorke. ‘Their accuracy allows for short delays with little risk of non-sequential firing. Furthermore, each detonator counts down independently – irrespective of whether the cable attached to it is cut. This means that blast planners can programme long delays without worrying about misfires caused by down line cut-offs.’ He adds that this makes timing designs more flexible, allowing for added complexity and more efficacy – which ultimately can change the mining method and significantly reduce costs.

Much to Rorke’s frustration, many mining companies fail to follow up the adoption of EDDs with any innovation in blasting practice.

‘My experience is that when operations convert from non-electric initiation systems to electronic detonators, there is a reluctance to give up the familiar 17×42 millisecond or 42×67 millisecond combinations, and miners impose these delay periods on EDDs,’ he says. ‘This restricts the benefits of electronics to only the accuracy component and ignores the much more powerful flexibility component.’

When a blast delay difference of a mere 20 milliseconds can make a massive difference to the blast, it quickly becomes clear just how delicate and precise the process really is. ‘No room for error,’ as AEL’s Van Soelen says. That precision will surely be sharpened by digitalisation. And as more firms – including BME, Orica and AEL – drive innovation in the explosives sector, safety and efficiency will only continue to improve.